[TV Review] Junji Ito Maniac: Japanese Tales of the Macabre (2023)

For years, I have been a woman obsessed with the sensational work of manga writer and artist Junji Ito. My reviews on “Uzumaki”, “Tomie,” and “Lovesickness” for Ghoul’s Magazine have shown my admiration for his work, creativity, and talent.

Junji Ito became somewhat of a legend amongst horror manga fans for his seminal work, Uzumaki (1998). Since then, he has developed a cult following for his other works, such as Tomie (1997), Gyo (2001), Hellstar Remina (2005) and his newer works, such as No Longer Human (2019) and Venus in the Blind Spot (2020). His hellish manga style has been a horror lover’s delight because of his incorporation of grotesque body horror. Junji Ito has experimented with everything, from heads split open to slugs emerging from people’s mouths and mutant fish. So naturally, when I heard that he was doing the original animation for the new Netflix series, “Junji Ito Maniac: Japanese Tales of the Macabre”, I was beyond excited to see the drawings from the manga pages that I was so desperately obsessed with finally come to life. This review will be of the series overall but it will delve deeper into some of my favourite hits and misses of the early episodes of the series, but also aims to explore the deeper themes at the core of the new Netflix series.

Episode 1.

The series starts with the first episode, “The Strange Hikizuri Siblings”, which focuses on the six Hikizuri siblings, Kazuya, Kinako, Shigaro, Narumi, Hitoshi and Misako, after the death of their parents. The family is portrayed as slightly dysfunctional, clearly coping with the loss of their parents, which affects the youngest member of the family, Misako, intensely. Throughout the episode, she constantly cries for her now-dead mother. The family are presented grotesquely, in an almost Addams family style depiction, taken straight from Junji Ito’s pages and replicated perfectly on screen.

The oldest son of the Hikizuri siblings, Kazuya, attempts to uphold the image of the breadwinner in the episode. He does this by pretending to go to work daily, despite not having a job. He does this as an attempt to set a good example for his younger siblings and maintain the little of the familial order that they have. His rationale for not working is that he believes the family has enough money. Therefore, working becomes pointless. This makes his character quite irritating through the self-righteous attitude that he displays, perhaps in a bid for power over his siblings. The bid for power is shown at the dinner table scene in which he becomes annoyed with brother Shigaro for eating too loudly, as he says that the notion of Shigaro eating is “unpleasant to watch”.

What The Strange Hikizuri Siblings demonstrates throughout is a dysfunctional family dynamic and the struggles of grief. Perhaps Grief is best shown with the little sister Misako, who clearly cannot cope with her mother's death. In turn, she physically assaults her brother Hitoshi (assumed to be the second youngest), often leaving him with scars, bruises, and scratches. Hitoshi, in turn, grieves not only the assault that he has to endure but the loss of his parents as well, and at a more nuanced level, he perhaps mourns the loss of his childhood as a direct consequence of the death of his parents. None of the siblings want to take responsibility for Misako or her behaviour, so the responsibility is often passed to Hitoshi. Indeed, his childhood did perhaps die with his parents’ passing. He becomes so traumatised by the attacks caused by Misako that he is almost like an empty vessel, eventually becoming possessed by his father's ghost. There is a constant rivalry between the other siblings too. One of the oldest sisters, Kinako, becomes jealous when her brother Shigaro states that their sister Narumi looks more like their mother than she does. In the same way, Shigaro clearly has repressed feelings of jealousy towards his older brother. This is evident because Shigaro pretends to be possessed to gain control over his family and replace Kazuya as the head of the household. However, when Shigaro is found to be a fraud, Kazuya regains his position, and Shigaro falls back into submission.

The first episode was far from scary but an apt commentary on the internal power struggles and trauma beyond the surface of family life, even a family as strange as the Hikizuri’s.

Episode 2.

“The Story of the Mysterious Tunnel” is one of the stories from the series that was deeply saddening but also highly frustrating because of the number of questions viewers had by the end of the episode.

Goro returns to the mysterious tunnel his mother once walked into as an act of attempted suicide, as implied by the sudden emergence of a train after her body wanders into the tunnel on the desolate train tracks. However, it is also possible that his mother disappeared in the tunnel as it has the ability to suck people into the walls, leaving their spirits to wander and torment those who enter. Again, this story, much like the story of the Hikizuri siblings, delves into the nature of family dynamics. Goro lives with his father and little sister, who all seemingly feel the devastation of their mother’s death. The story is sombre, as Goro loses his little sister, father, and eventually himself in this mysterious tunnel. However, the episode leaves viewers with many unanswered questions about the nature of the tunnel. Why does it suck people into its walls? Is there a pattern to the nature of the killings connected to the tunnel? Did Goro’s mom kill herself initially because she wanted to, or was she just another one of the tunnel's victims? I couldn’t help but feel frustrated at the ending. Nevertheless, sometimes that is the nature of horror; it can be unexplainable and sometimes we never get the answers to the questions we so desperately crave.

The episode then switches to the story of “The Ice Cream Bus”. The ice cream bus is driven by a mysterious man whom the city's children love as he drives them around the town and allows them to lick a pile of ice cream on the floor. This episode raises questions about parental supervision and shows the parents of these children to be quite naive, especially to the true evil nature of the ice cream bus. It turns out that the ice cream the children are consuming was once actually human beings. Dad Sonohara finds his son’s friends have turned into different flavours of ice cream whilst his son licks away in absolute bliss. Again, the episode raises several questions. Who is the ice cream man? Where did the ice cream truck come from? Is the ice cream symbolic of the consumption of the young? Does the more youthful generation literally thrive on symbolically consuming one another? The Ice Cream bus gives viewers much food for thought (pardon the pun).

LISTEN TO OUR HORROR PODCAST!

Episodes 3 & 4.

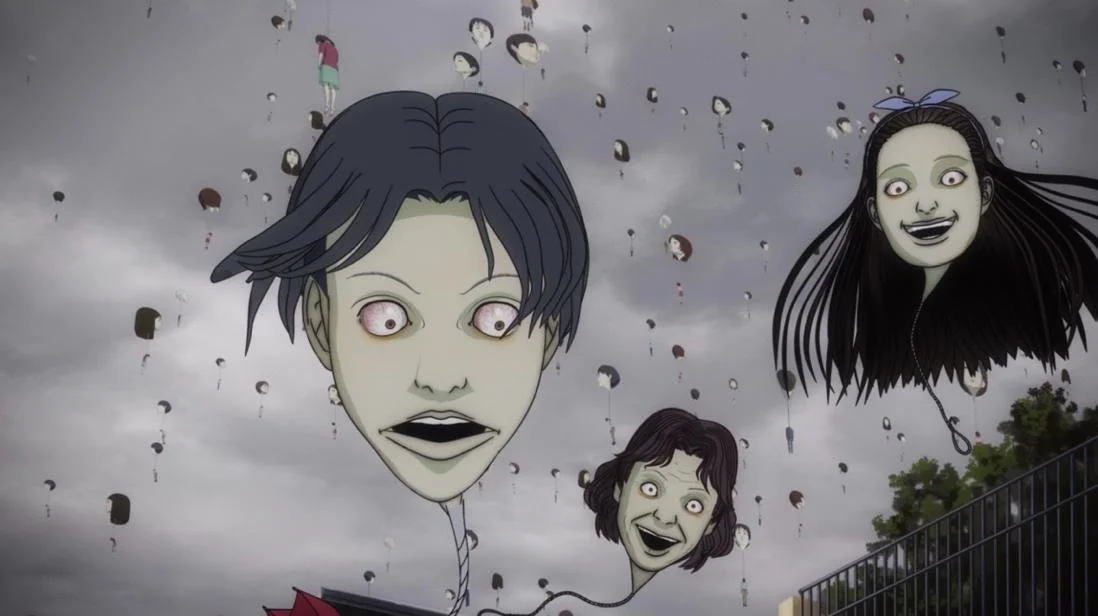

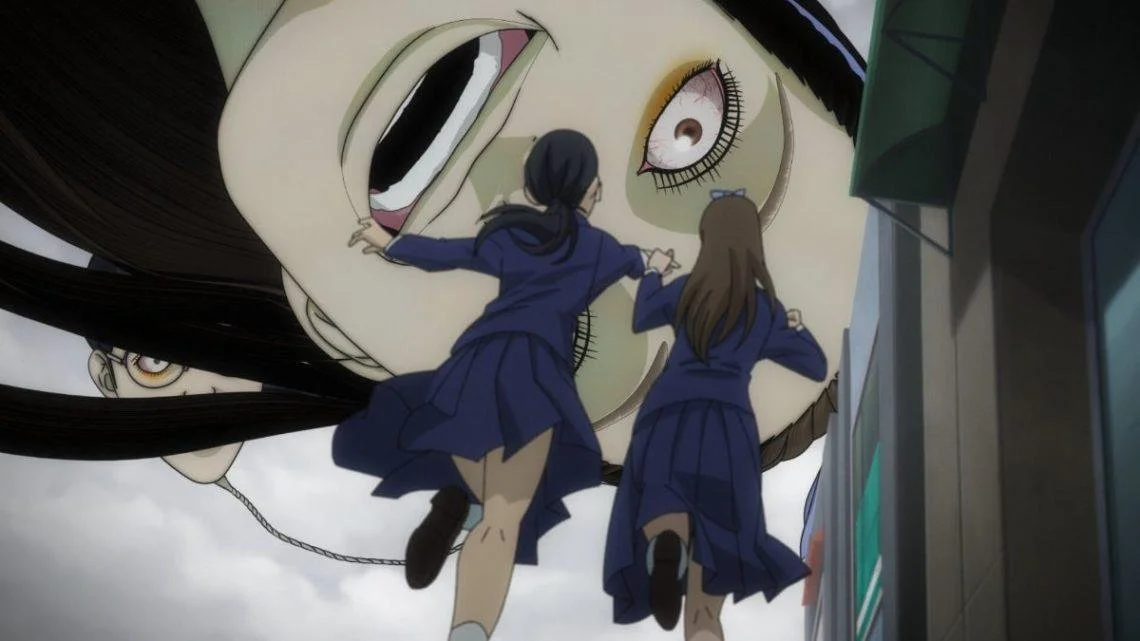

The rest of the episodes are generally good and bring important issues and themes to the forefront, such as Episode 3, “Hanging Balloon”.

This is perhaps one of my favourites of the series; I was instantly sucked into the tragic story from the beginning. Japanese idol Terumi Fujino seemingly commits suicide, and the episode raises questions about the trauma of suicide, idol worship, and mass hysteria. Balloon-shaped human heads with a hanging noose at the end of torment a city and lead to the mass suicide/murders of everyone in the affected area. The heads are of actual people who live in the town, track them down, and hang them. The hellish imagery of head-shaped balloons that hang people is the stuff made of nightmares and classic Ito. This story made me nostalgic for Ito’s classic mangas.

My least favourite of the episodes was episode 4, “Four x Four Walls”.

Souichi, a strange and pale-looking boy who likes biting on nails, torments his older brother Kouichi by constantly playing tricks on him. Souichi often imitates poltergeists to annoy his brother and distract him from his studies. Souichi is a lot more sinister and macabre in Junji Ito’s manga, which does not translate into the series, where he is depicted as annoying and slightly frustrating. This, coupled with his parent’s reluctance to punish him and his weird connection with the creepy carpenter, left me feeling quite infuriated. Viewers are again left with numerous questions at the end of the episode: Did Souichi die? Did he and the creepy carpenter have a satanic deal of some sort? Who was the carpenter, and why was he relevant to the story? I was left frustrated as the level of horror was just not there. The episode then switches to “The Sandman’s Lair”, which was incredible. This episode also highlights broader themes of mental illness, multiple personality disorders and the blurred lines of reality and fiction. Yuji Hirano asks his friend Mari to keep him awake, as his “sleep” self is trying to take over his “awake self”. Grotesque from the very moment Yuji closes his eyes, and viewers see the dream Yuji’s hand protruding from awake Yuji’s body was the stuff made of nightmares, and indeed left me with feelings of dread. Perhaps this was an ode to older horror, which crosses the boundaries of the dream world and reality, such as A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984).

Concluding thoughts.

It is fair to say that viewers should treat Junji Ito’s mangas as a separate entity from the new Netflix series. Whilst the mangas typically focus on the true nature of body horror, gore and fright, this does not necessarily translate to the Netflix series. The Netflix series seems to delve into the heart of core societal issues, such as the dysfunctional nuclear family, grief, trauma, and suicide. The series makes viewers think about what is essential and how we would react if we were in the situations that Ito’s characters find themselves in. And as mentioned before, although some of the early episodes leave the viewers with questions, perhaps that is what the Netflix show gets right. That is one of the most authentic things about the nature of horror, sometimes things are unexplainable, and we do not always get the answers we desperately crave – and that for humans and the human consciousness is scary; the unknown.

The series is available to watch on Netflix.

![[Ghouls Podcast] You Are Not My Mother with Ygraine Hackett-Cantabrana](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840165939-VP0CIKOM4KPX67JLNHDB/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+6.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Wicker Man with Lakkaya Palmer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839898764-VIYDC7ZD8QTBCGK562NL/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+7.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Noroi: The Curse & Perfect Blue with Sarah Miles and Ygraine Hackett-Cantabrana](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682950816911-7ZCMPP8H0BSUPCPZYQ07/_PODCAST%2BNO%2BIMAGE%2B2023%2BEP%2B8.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Dark Water with Melissa Cox and Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839939630-BLPIHIDVRJE9FC1A9BRZ/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+9.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination with Jenn Adams and Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839916928-KK9CTT0OAKACXLGYA9DX/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+10.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Alien with Tim Coleman and Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839878802-LR40C39YGO3Q69UCCM62/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+11.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Horror Literature with Nina Book Slayer & Alex Bookubus](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840273346-ASHBRDHOKRHMGRM9B5TF/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+12.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Halloween Special: 5 Horror Films to Watch This Halloween with Joshua Tonks and Liz Bishop](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840351086-2AWFIS211HR6GUY0IB7I/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+13.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Soho Horror Film Preview with Hannah Ogilvie & Caitlyn Downs](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840411619-IP54V5099H6QU9FG4HJP/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+14.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Borderlands (2013) with Jen Handorf](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839985316-KPLOVA9NGQDAS8Z6EIM9/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+15.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Soho Horror Film Review with Hannah Ogilvie & Caitlyn Downs](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840392291-XQGQ94ZN9PTC4PK9DTN1/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+16.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Krampus (2015) with Megan Kenny & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839790368-VYX6LIWC5NVVO8B4CINW/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+17.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Terrifier (2016) & Terrifier 2 (2022) with Janine Pipe](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1674478017541-0DHH2T9H3MVCAMRBW1O1/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+4+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Loved Ones (2009) with Liz Bishop](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1676369735666-56HEK7SVX9L2OTMT3H3E/GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Severance, Run Sweetheart Run, Splice & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677589685406-YZ9GERUDIE9VZ96FOF10/Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Good For Her Horror Film Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678634497037-W441LL37NW0092IYI57D/Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] 5 Coming-of-Age Horror Film Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1681418402835-EMZ93U7CR3BE2AQ1DVH4/S2+EP5.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Deathproof, Child’s Play, Ghostwatch & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682447065521-DWF4ZNYTSU4NUVL85ZR0/ghouls+watch.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Ruins (2008) with Ash Millman & Zoë Rose Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684076097566-BE25ZBBECZ7Q2P7R4JT4/The+Ruins.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: The Devil’s Candy, Morgana, Dead Ringers & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685284429090-5XOOBIOI8S4K6LP5U4EM/%5BMay%5D+Ghouls+Watch+-+Website.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] 3 Original vs. Remake Horror Films with Rebecca McCallum & Kim Morrison](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685286663069-0Q5RTYJRNWJ3XKS8HXLR/%5BJune%5D+Original+vs.+Remake+Horror+Films.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Bones and All, Suitable Flesh, The Human Centipede & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687855203348-7R2KUSNR6TORG2DKR0JF/%5BJune%5D+Ghouls+Watch+-+Website.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Body Horror Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691238687847-L9U434I1U4HZ3QMUI3ZP/%5BJuly%5D+Ghouls+Watch+-+Website+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Antiviral, Possessor & Infinity Pool with Zoë Rose Smith, Amber T and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691238787263-XYRKXW2Z7RWI9AY2V2GX/%5BJuly%5D+Antiviral%2C+possesoor+and+infinity+pool+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Tender Is The Flesh with Zoë Rose Smith, Bel Morrigan and Liz Bishop](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693769261264-MS4TS4Z4QC1N15IXB4FU/Copy+of+%5BJuly%5D+Antiviral%2C+possesoor+and+infinity+pool.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Bucket List of the Dead, Blood Drive, Candy Land & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696261000263-58VQFOVWPE363OFGP7RF/GHOULS+WATCH.jpg)

![[Film Review] Sympathy for the Devil (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186986143-QDVLQZH6517LLST682T8/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.48.52.png)

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Film Review] A Wounded Fawn (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484054446-7R9YKPA0L5ZBHJH4M8BL/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.42.24.png)