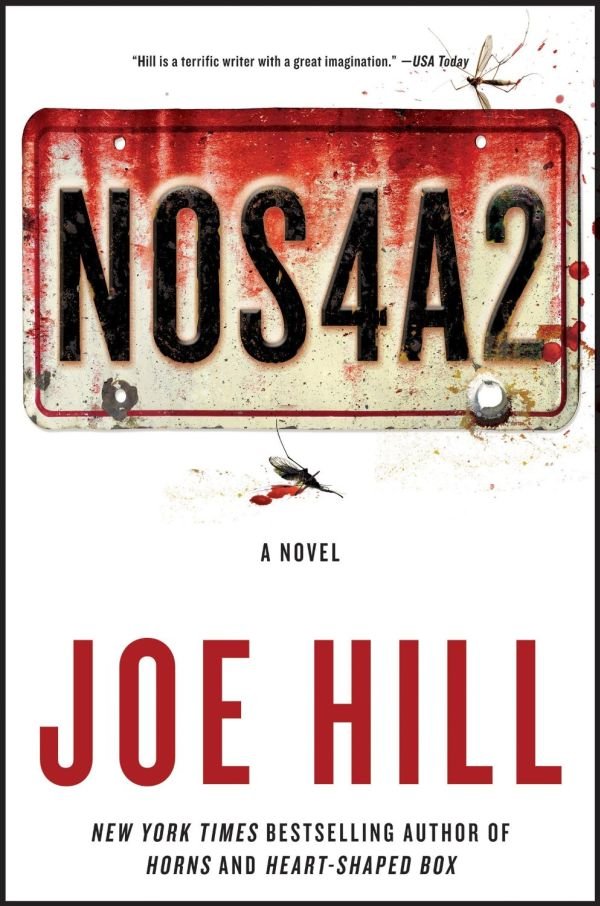

[Book Review] Nos4a2 (2013)

Using echoes of childhood nostalgia reminiscent of Peter Pan or Goonies, Joe Hill’s Nos4a2 (2013) twists childlike wonder into bloody debasement—hammering home the point: growing up isn’t easy but you sure as hell have to do it.

The story opens with the protagonist Vic as a young girl. One fateful day she rides her bike to the Shorter-Way Bridge, which she’s been warned never to approach. Like any curious child, she crosses anyway. Rather than falling to her death, she’s met with static and a headache. Once across, she’s in a restaurant from earlier that day, where she finds her mother’s missing bracelet. This marks a turning point in Vic’s life, as she realizes that her bike and the bridge can take her anywhere she wants.

Called inscapes, mystical objects like the bridge confer power upon particularly creative individuals. For instance, a man named Charlie Manx has a curious penchant for the imaginary. His inscape, a 1938 Rolls-Royce Wraith, lets him go into his mind, where Christmasland and its eternal children reside.

Christmasland is the most obvious example of Hill’s blending of whimsy and terror. To get kids to his inscape, Manx kidnaps them and forces their souls into ornaments. By the time they arrive and inhabit Manx’s mind, they’re no longer human—just blood-thirsty monsters cursed with eternal life. The connection to JM Barrie’s lost boys is sinister but obvious.

Manx, in his own twisted way, believes that keeping children in Christmasland preserves their innocence. He also enjoys the added benefit of keeping their souls to maintain his youth.

Those most concerned with innocence do so to maintain power. In patriarchy, for example, women are judged for engaging in sex. This isn’t based on any scientific reasoning but allows men to gain more control through infantilization. Sexual knowledge can lead to personal empowerment, better judgment and lessons in consent. In this way, childhood is the basis for control. Manx’s inscape and motives are inherently tied to his life force and, therefore, work exclusively to his benefit. With each soul he takes, he grows younger and healthier. He forces children into stasis to become young again. And, by keeping them in his world, he can leverage them to torture Vic and tempt other children.

When Vic avoids Manx’s grasp, she proves that Manx isn’t owed the authority he claims.

On a more theoretical level, Hill uses Manx and Christmasland to show the evil’s of innocence. While reminiscing on the past is normal, staying there also means never moving forward. As Keats put it in Ode on a Grecian Urn: “Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss/Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve;/ She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss.” If we remain static, we lose access to the positive experiences yet to come.

Besides Christmasland, the inscapes themselves present a meta-analysis of horror. Like his father Stephen King, Hill imbues his story with a sense of adventure commonly found in middle-grade fantasy. Several of King’s novels center on plucky kids fighting against some looming entity. Hill takes this concept a step further, not only introducing Vic as a young girl but granting her access to a bridge that transports her to any place she desires. It’s the perfect lead-in to a fantasy story where the monsters might be trolls, witches or dragons and goodness always prevails.

Instead, each trip through the Shorter-Way gives Vic blinding headaches and illnesses that worsen the longer she stays on the other side. And the bridge doesn’t take her any place Manx can’t get to as well. Hill imagines a world in which many people have access to childlike whimsy and use it to their advantage. Manx maims and kills several parents and causes Vic great bodily and psychological harm. Nos4a2 shows that the stories that enthralled us can scare us too, forcing the reader to grow up.

Like the bridge, The Wraith has a catch-- it takes away Manx’s soul. Or, more accurately, becomes his soul. If anyone destroys the car, Manx dies too. Conversely, if someone puts it back together, Manx comes back to life. While it’s not tied to childhood, it is vintage-- harkening back to “simpler times” where kids valued family and women knew their place. To emphasize this point, Manx’s first victims are his own daughters.

Vic herself is the final symbol of growth (or lack thereof). She and Manx first meet when she takes the Shorter-Way to Manx’s home so she can be kidnapped to spite her mother—a logic characteristic of an adolescent mind. There she discovers a monster child and narrowly escapes Manx before she sets his home ablaze. From there, she leads a troubled life as a children’s book illustrator—always haunted by Manx.

Vic loses her bike in her escape, making it impossible for her to use the Shorter-Way Bridge for most of her adult life. In this way, at least, Vic grows up. It isn’t necessarily a life filled with happiness, but she is able to raise a family and find a partner who loves her (even if it doesn’t work out).

Though she can’t use her inscape, Vic still receives mysterious calls from monstrous children and never overcomes the trauma of her parents’ divorce and father’s abandonment. Vic’s real troubles all lie in the past. It is only through Manx’s violent destruction that Vic overcomes her pain. She ends up sacrificing herself but it’s for the good of her son—the sole child who manages to survive Manx and, therefore, carry on with his life. It’s through Vic finally, really, truly taking action that Manx is defeated. She no longer allows the stasis of his world to freeze her own progression. While she doesn’t live forever, she does live and that’s what counts.

![[Book Review] Wylding Hall (2015)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484930026-PFRK7O26SLME4JIC49EW/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.59.04.png)

![[Book Review] Penance (2023) by Eliza Clark](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695481011772-L4DNTNPSHLG2BQ69CZC1/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.54.07.png)

![[Book Review] The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328003764-IASXC6UJB2B3JCDQUVGP/61q9oHE0ddL._AC_UF1000%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Nineteen Claws And A Black Bird (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685872305328-UE9QXAELX0P9YLROCOJU/62919399._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Manhunt (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1683911513884-1Q1IGIU9O5X5BTLBXHV9/53329296._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Eyes Guts Throat Bones (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682344253308-4AAFX12YD84EVJBYNJBZ/7e617654-8d9e-407e-8cde-33a97df84dcf.__CR0%2C0%2C970%2C600_PT0_SX970_V1___.jpg)

![[Book Review] Cursed Bunny (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1680266256479-2E2XJT4T8CGAMOUB7XAL/298618053_5552736738082400_5168089788506882676_n.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Aosawa Murders (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678009096264-7QOOFO5PI9LAX47L3GF6/51054767.jpg)

![[Book Review] Hear Us Scream Vol II](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667055587557-4AIJTAG4N5VUZE8AC0SF/FrontCoverMarinaCollings.png)

![[Film Review] Lure (2026)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1770395940296-FY9ZVDC6XY5XV8ORD963/lure+7_1.628.1.jpeg)

![[Film Review] Garden of Love (2003)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769673863857-NUT1DRKMHFBWXFUMBHSQ/GARDEN+OF+LOVE.jpg)

![[Film Review] I Know Exactly How You Die (2026)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769676255638-ZVMA90E485FFL1Q65GZZ/I+KNOW+EXACTLY+HOW+YOU+DIE.jpg)

![[Film Review] We Bury the Dead (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769675442473-7E5FPBEDFXIAM5VK9WYG/WE+BURY+THE+DEAD.png)

![[Film Review] A Desert (2024)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769849903159-4AW0HY78DWOU6JSBCQER/A-Desert.webp)

![[Film Review] Primate (2026)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769671865937-O45HQB0QV31RG2HSQVLJ/PRIMATE.jpg)

![[Film Review] Return to Silent Hill (2026)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769672582439-C8RQWP3CYUW1JX4ZRNLE/RETURN+TO+SILENT+HILL.jpg)

![[Film Review] Flights of Reverie (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1769111579457-CTUW03G3J34P6SFRWWEM/flights-of-reverie-filmstill-ornithologist-berlin-li-wallis06.jpg)

Happily, her new anthology The Book of Queer Saints Volume II is being released this October. With this new collection, queer horror takes center stage.