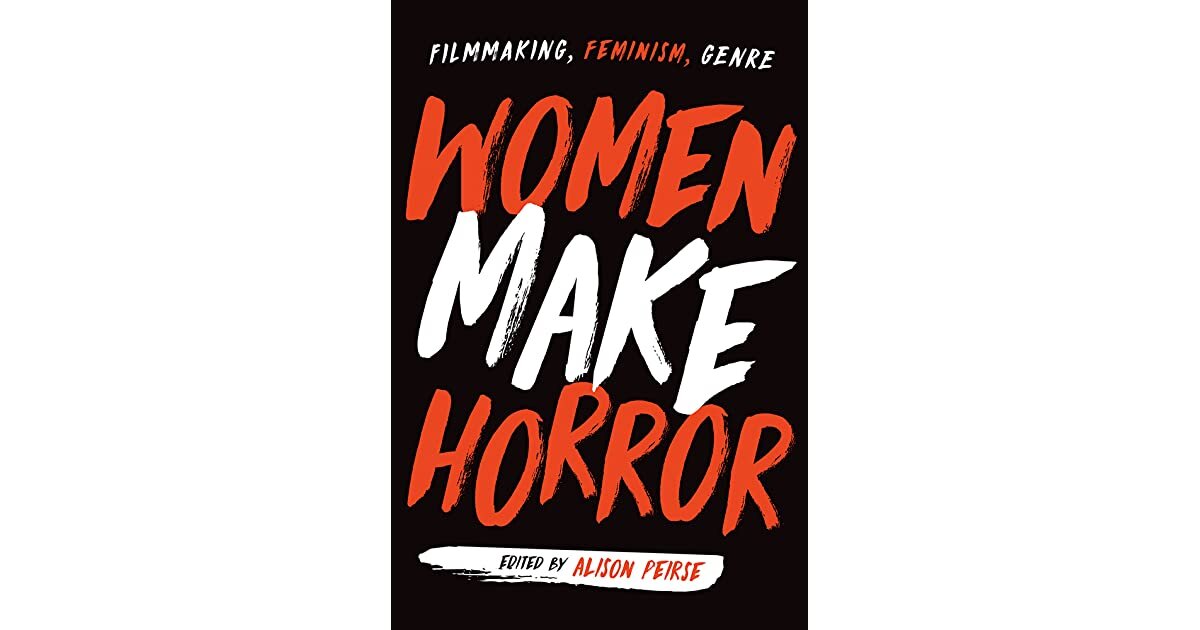

[Book Review] Women Make Horror (2020)

With a welcome focus being shone on female creators within horror resurging in recent years, it is easy to assume that we are well versed as a community about the position of women in horror history and how this has informed where we stand today.

In her introduction of Women Make Horror, editor Alison Peirse sets out the framework for gathering her contributions whilst also meditating on key themes that will recur throughout the book. Amongst these is the fact that women working within the horror industry is not a sudden revelation that has only happened since the 2010’s, or even within the last five years, but in reality women have always been making horror; they were just never given the space for recognition and acknowledgement. Writing women into the narrative of horror history is equally as important as ensuring that, when looking to the future, women have the opportunity to create and bring to the table their own unique perspective on the genre.

Pierse’s three underpinning questions to the writers who make up the volume were as follows: can horror cinema be women’s cinema, what stories are told in women-made horror (and how do these differ from stories told by men) and what makes a horror film a feminist film. Using these as guiding points, the 17 chapters explore rewriting women back into horror history, examining female-directed films and women’s involvement in the creation of horror.

The focus extends from analysis of specific films (including horror shorts and anthology films) and careers, to the impact of horror communities through festivals and the increase of the female horror filmmaker fan. The book also explores the many misconceptions that exist around the genre, including that women are less likely to engage with horror. On the contrary, many writers argue that horror made by women is enriched by their very willingness to move towards violence and physical and psychological trauma, rather than turning away from it.

Individually the chapters offer plenty of thinking points and excellent references should the reader wish to deepen their knowledge in any specific area. However, the power of Women Make Horror resides in its totality and in reading these contributions as a collective which allows for shared themes to blossom and emerge. Several chapters shed light on the disheartening fact that men have repeatedly been credited for work undertaken by their female counterparts and there are common threads around the issues of gender, sex, trauma and the struggle of the individual.

In addition to this, there are questions raised about the issue of authorship, with women frequently being denied this because it doesn’t fit the narrative set by men. What is clear is that whilst there is a wonderful abundance of women making horror, they are, regrettably, more prone to invisibility.

While many women discussed in this book have enjoyed successful and fulfilling careers, there are too many who have systematically been thrust out of the limelight and have sadly been on the end of hostile attacks. It would certainly seem that in some pockets of the industry, men are happy to reap the praise and recognition when it is positive (and fail to acknowledge their fellow female creators) but when the tide turns away from their favour, the finger of blame is pointed firmly in the direction of their female colleagues.

It would be unfair to single out any particular chapter (and there are too many to list them all) because the strength of this volume lies in its power to bring together a multitude of voices and perspectives. While there are chapters featuring fan favourites such as Suspiria, Ginger Snaps and American Psycho there is importantly, a space carved out for exploring international horror with chapters on the New French Extremity, Latin America, Korean cinema and the Australian female gothic.

Women Make Horror would make an invaluable reference tool for anyone writing about or creating horror as its scope is broad and varying. Its tone is heavily academic but so rich in its offerings that there is no doubt that repeated readings will provide a rewarding experience. Upon finishing the book, I found to my great delight that I had amassed a treasure trove list of previously undiscovered films, festivals and resources to sink my teeth into. As a woman who often writes from a feminist perspective, I found this collection of essays (the first all-female and female edited book of its kind) deeply moving, oftentimes upsetting and always incredibly inspirational. As one contributor remarks: ‘the impossible can only become possible when we know it is already being done’.

![[Book Review] Wylding Hall (2015)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484930026-PFRK7O26SLME4JIC49EW/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.59.04.png)

![[Book Review] The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328003764-IASXC6UJB2B3JCDQUVGP/61q9oHE0ddL._AC_UF1000%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Manhunt (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1683911513884-1Q1IGIU9O5X5BTLBXHV9/53329296._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Hear Us Scream Vol II](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667055587557-4AIJTAG4N5VUZE8AC0SF/FrontCoverMarinaCollings.png)

![[Book Review] Eyes Guts Throat Bones (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682344253308-4AAFX12YD84EVJBYNJBZ/7e617654-8d9e-407e-8cde-33a97df84dcf.__CR0%2C0%2C970%2C600_PT0_SX970_V1___.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Book of Queer Saints Volume II (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697187383073-U78VOF5WVDHI9YE8M98A/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.52.31.png)

![[Book Review] Cursed Bunny (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1680266256479-2E2XJT4T8CGAMOUB7XAL/298618053_5552736738082400_5168089788506882676_n.jpg)

![[Book Review] Nineteen Claws And A Black Bird (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685872305328-UE9QXAELX0P9YLROCOJU/62919399._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Penance (2023) by Eliza Clark](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695481011772-L4DNTNPSHLG2BQ69CZC1/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.54.07.png)

![[Film Review] Sympathy for the Devil (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186986143-QDVLQZH6517LLST682T8/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.48.52.png)

![[Film Review] Mercy Falls (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695482997293-E97CW9IABZHT2CPWAJRP/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.27.27.png)

![[Film Review] Perpetrator (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695483561785-VT1MZOMRR7Z1HJODF6H0/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.32.55.png)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Film Review] A Wounded Fawn (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484054446-7R9YKPA0L5ZBHJH4M8BL/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.42.24.png)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

A girl stands with her back to the viewer, quietly defiant in her youthful blue-and-white print dress, which blends in with a matching background