[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)

In the sweaty summer of 1989, emerging like a monochrome migraine from the encroaching shadow of Japan’s economic crash, Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man shocked and disgusted the (very few) audiences originally in attendance. The hyperkinetic tokusatsu, directly inspired by the works of David Lynch and Cronenberg, follows a salaryman’s (Tomorowo Taguchi) nightmarish descent into metallic insanity as he realizes his body is being transformed at the behest of a mysterious Metal Fetishist (played by Tsukamoto himself). With its diminutive budget and boundless imagination, Tetsuo: The Iron Man has retained its passionate cult following even three decades after its initial release. As one of the pinnacles of cyberpunk cinema, Tetsuo cemented Shin’ya Tsukamoto not only as one of Japanese genre cinema’s most treasured and transgressive auteurs, but one of the country’s experts in the craft of body horror.

Body horror – or more accurately, the horror of having a body - has been an inextricable part of my life since I developed body dysmorphic disorder at a relatively young age. Over time, I have written extensively about my body, obsessed over every inch, every mark - my chipped teeth and broken nails, bloodied cuticles and bruised knees. I remember in excruciating detail the first time I ever felt ugly as a 12 year old on the cusp of puberty, doused with dread at the possibility of a whole new world of self-hatred to navigate. Since then (like most of us, shall we say, ‘mentally afflicted’ horror fans) I have consistently sought out cinema that reflects the wrathful workings of a body in strife – enter Tetsuo.

It might be hard for some to envision that a film so filthy, fetishistic, and nauseatingly contorted against any traditional viewing experience could ever provide relief or reassurance in any form, but comfort comes from an unlikely place. Tetsuo is a live wire on a raw nerve, an ear-splitting scream so savage it’s almost comical - a state of being I myself am all too familiar with, especially when confronted with a mirror. And so more than the more traditional ‘good for her’ narratives of feminine rage, I found myself drawn to the unrelenting, unforgiving rage of Tetsuo, in all its masculine fury. After all, I have never felt feminine or soft. My body has always felt sharp, angular, hostile, and aggressive - a plane of rusted scrap metal ready to pierce or scrape anyone who got too close. I have always seen my body as a battle, as a blade, as a cog in a machine that grinds with no purpose.

It makes sense then that, visually at least, I found myself completely hypnotized by the high-octane, savage surrealism of Tetsuo, rather than something like Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, a similarly dysmorphic tale with a much more palatable cinematic style. I could never relate to Natalie Portman’s gentle blush, soft cardigans, or girlish, demure nature – but immediately saw myself in Nobu Kanaoka’s maniacal, metal-handed Woman with Glasses, or Kei Fujiwara’s drill-dick-wielding Woman. I know this film. I have felt its jagged edges as my own. I have even smelled this movie, familiar as I have become with the sanguineous scent of blood-stained metal, as I gouge and slice out imagined flaws with all the grace and precision of a maniacal surgeon.

Undoubtedly, for all its grit and grime, Tetsuo is a truly unique and striking film – two descriptors I have always found to be more enticing than beautiful. I try to apply this same narrative to myself. My teeth might be gapped and my skin sallow, but there is nobody and nothing on earth that looks like me - I am a fucking behemoth of steel and spit and sour sweat. I simultaneously long to sear my image into the brain of every human on this earth, and at once cease to exist.

Of course, just as a similarly iconic body horror film once reassured us “don’t be afraid to let your body die”, Tetsuo understands that separation of the self is perhaps the only way to ever fully gain true emancipation from the hell of a tortured mind. With its transhumanist themes applicable to everything from anti-capitalism to trans rights, Tetsuo posits the destruction and metamorphosis of the body as equally liberating and traumatizing. As demonstrated by every character in this strange and sick little world of metal, there is the desire to sublimate flesh into something more substantial, to free oneself from the inescapable horrors of aging, sickness and dying, and become something braver, stronger, unencumbered from the existential insecurities that come simply from being a human.

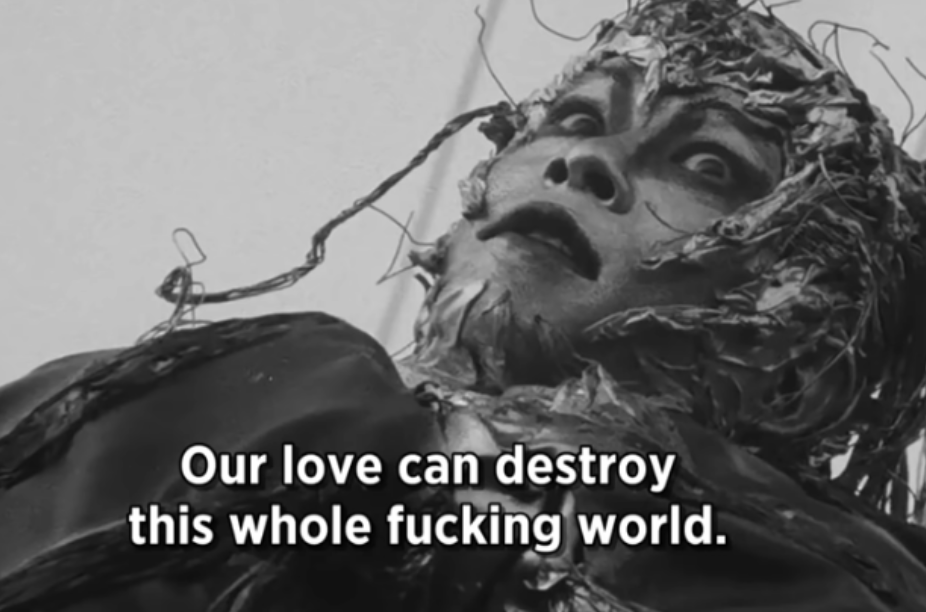

For me, Tetsuo represents a state of freedom from the shackles of society’s – and my own – expectations of my body as a woman. This is why, despite its hilariously chaotic ending where the Metal Fetishist and the Salaryman are fused together in a twitching amalgamation of flesh and metal, Tetsuo is a love story. A love story between me and my body, with all its flaws and fury. To rust the world and its expectations into dust. Tetsuo is a spark of steel hope that one day I can look at my body and say ‘our love can destroy this whole fucking world.’

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)