[Editorial] The Complicated History of the Lesbian Vampire

“You will think me cruel, very selfish, but love is always selfish.” — Carmilla, Sheridan LeFanu, 1872

There is perhaps no monster in our western glossary of beasts more adaptable and ready to be an allegory than the vampire. Over centuries they’ve moved from primal undead corpses to impossibly beautiful lovers. They’ve been demons and animals, they’ve been teen heartthrobs and bad boys, they’ve been metaphors for our worst nature and Byronic heroes. They have also, on occasion, been lesbians.

Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla lives in the shadow of the much more famous Dracula by Bram Stoker, but it actually predates that story by over 20 years. In fact, there’s a lot of evidence to suggest Stoker took many of his now commonplace vampire tropes from what he read in LeFanu’s story: the vampire as European nobility, the vampire hunter saving the day, the young maid suffering sexual advances from the vampire, sleepwalking as it relates to vampiric control, and the combination of Gothic horror and mystery story.

The novella takes place in the Austrian territory of Styria where our protagonist Laura is staying with her father. One day, a seemingly ill young woman comes to stay with them while she recovers. Laura and the young woman, Carmilla, start an intense companionship that, in the night, seems to become sexual and even supernatural. As Carmilla’s strength returns, Laura’s wanes. It becomes clear that Carmilla is a vampire said to live in the area, several centuries old, and feeding on Laura both emotionally and physically. Only when vampire expert and hunter, Baron Vordenberg, locates Carmilla’s tomb and drives a stake through her heart does the parasitism end.

On paper, it sounds like LeFanu is certainly making some kind of statement about female sexuality and, specifically, sapphic attachments between women. But, a closer study reveals a murkier picture. LeFanu’s protagonist, Laura, has come to be seen as a representation of Victorian women: lively, capable, and incredibly stifled by the bumbling men of her time. In fact, LeFanu goes out of his way to paint the men who surround Laura—her father, Baron Vordenberg—as rather distracted, unhelpful, and even a hindrance to her. Meanwhile, with Carmilla, she shares an intense bond and a strange commingling of attraction and repulsion. While it’s easy to read the story as LeFanu condemning sapphic relationships between women and female sexuality in general, it seems more nuanced than that. Carmilla has come to represent temptation itself, the dark side of human nature and human desire. Something the men in Laura’s life insist is evil but that Laura herself has a much more complicated relationship with. And, in the end, Laura never fully recovers from the events of the book, suggesting a loss of innocence and coming of age. These are the kinds of stories women didn’t have in LeFanu’s time.

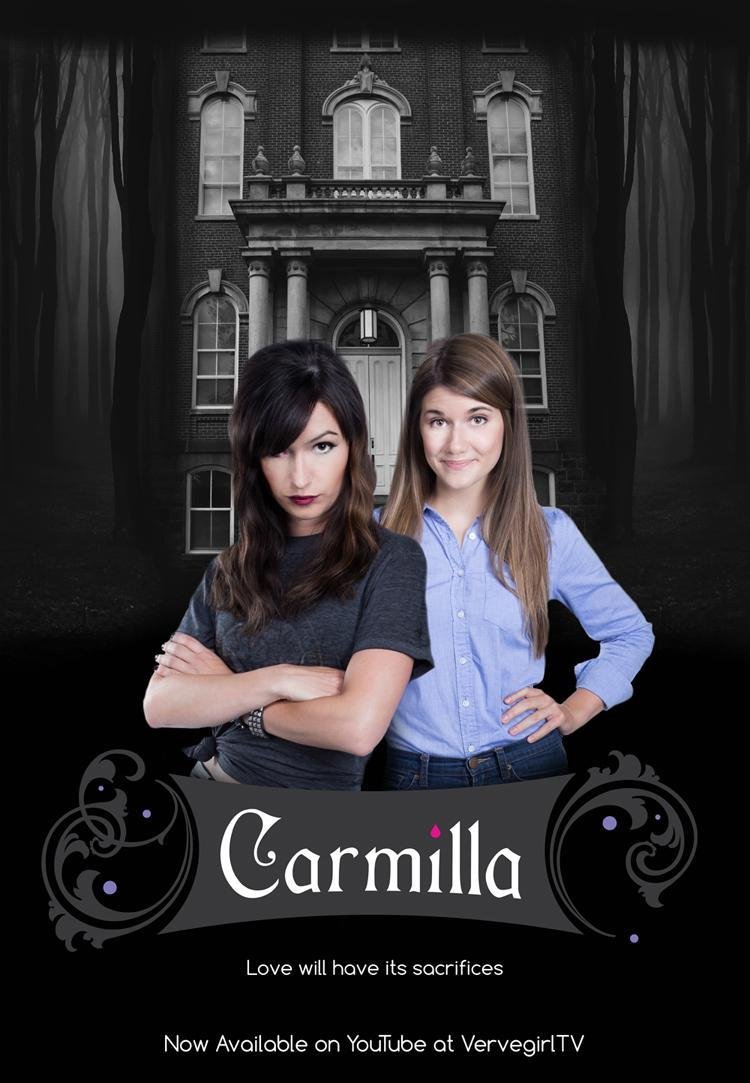

Since the original novella, Carmilla has popped up all over vampire media: Castlevania, Doctor Who, True Blood, The Mortal Instruments. She has been the star of her own adaptations in books, TV, and film. Perhaps the most recognizable piece of media to feature the character and her story is the Canadian web series Carmilla, starring Elisa Bauman as Laura and Natasha Negovanlis as the title character. Writer Jordan Hall reimagines the novella in a college dorm, portraying Laura and Carmilla as freshman roommates on a Nightvale-inspired campus run by a vampire cabal and other dark creatures. With several queer creatives both in front of and behind the camera along with a host of queer characters, the adaptation did more than modernizing the setting. It modernized the out-of-date commentary on queerness and feminity. Further, it contended with its own legacy in the indie-film adaptation The Carmilla Movie in a rather trippy way where the antagonist Elle Sheridan (Dominque Provost-Chalkey) represents the “Laura” of the original novella, resentful of the life she could not have.

What Carmilla and the many adaptations of the story ultimately tell us is that sexuality and how the queer community responds to its portrayal in media is not a monolith. Many find the original story incredibly damaging for queer women’s representation in culture. Others have found that LeFanu was giving female sexuality the ability to shine in a way it had not before. There’s no right answer in how to respond to it. But the many adaptations over the years give each new generation the ability to see layers, add to the mythos, and give one of literature’s most overlooked and misunderstood villains a chance to shine.

RELATED ARTICLES

Films that blend horror with romance always fascinate me; add a niche contemporary setting that I’ve never heard of before and I’m hooked. Cannibal Mukbang was made by Aimee Kuge, a young woman from New York, and I was privileged to spend a little time talking with her over Zoom…

In the six years since its release the Nintendo Switch has amassed an extensive catalogue of games, with everything from puzzle platformer games to cute farming sims to, uh, whatever Waifu Uncovered is.

A Quiet Place (2018) opens 89 days after a race of extremely sound-sensitive creatures show up on Earth, perhaps from an exterritorial source. If you make any noise, even the slightest sound, you’re likely to be pounced upon by these extremely strong and staggeringly fast creatures and suffer a brutal death.

Have I told you about Mayhem Film Festival before? It’s a favourite event of mine, so I’ve blurted about it in anticipation to many people I know. The event has just passed, so now is the time to gush its praises to those I don’t know.

Loop Track, Thomas Sainsbury’s directorial debut, has such a sparse description that it’s really difficult to know what you’re stepping into when it starts. It’s about Ian (played by the director), who is taking a trek through the New Zealand bush….

For a movie that doesn’t even mention the word “vampire” once throughout the length of the film, Near Dark (1987) is a unique entry in the vampire film genre.

If you like cults, sacrificial parties, and lesbian undertones then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the book for you. Samantha, a student at a prestigious art university, feels isolated from her cliquey classmates, ‘the bunnies’.

Kicking off on Tuesday 17th October, the 2023 edition considers the cinematic, social and cultural significance of the possessed, supernatural and unclean body onscreen.

I was aware of the COVID-19 pandemic before I knew that’s what it would be called, and before it ever affected me personally. My husband is always on top of world events, and in late 2019, he explained what was happening around the globe.

EXPLORE

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.

In the six years since its release the Nintendo Switch has amassed an extensive catalogue of games, with everything from puzzle platformer games to cute farming sims to, uh, whatever Waifu Uncovered is.

A Quiet Place (2018) opens 89 days after a race of extremely sound-sensitive creatures show up on Earth, perhaps from an exterritorial source. If you make any noise, even the slightest sound, you’re likely to be pounced upon by these extremely strong and staggeringly fast creatures and suffer a brutal death.

If you like cults, sacrificial parties, and lesbian undertones then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the book for you. Samantha, a student at a prestigious art university, feels isolated from her cliquey classmates, ‘the bunnies’.

The slasher sub genre has always been huge in the world of horror, but after the ‘70s and ‘80s introduced classic characters like Freddy Krueger, Michael Myers, Leatherface, and Jason, it’s not harsh to say that the ‘90s was slightly lacking in the icon department.

Mother is God in the eyes of a child, and it seems God has abandoned the town of Silent Hill. Silent Hill is not a place you want to visit.

Being able to see into the future or back into the past is a superpower that a lot of us would like to have. And while it may seem cool, in horror movies it usually involves characters being sucked into terrifying situations as they try to save themselves or other people with the information they’ve gleaned in their visions.

Both the original Pet Sematary (1989) and its 2019 remake are stories about the way death and grief can affect people in different ways. And while the films centre on Louis Creed and his increasingly terrible decision-making process, there’s no doubt that the story wouldn’t pack the same punch or make the same sense without his wife, Rachel.

The story focuses on a group of survivors after most of the world’s population is wiped out by Captain Trips, a lethal super-flu. And while there are enough horrors to go around in a story like this, the real focus of King’s book is how those who survive react to the changing world around them.

While some films successfully opt to leave the transformation scene out completely, like the wonderful Dog Soldiers (2002), those who decide to include it need to make sure they get it right, or it can kill the whole vibe of the film. So load up on silver bullets, mark your calendar for the next full moon, and check out 11 of the best werewolf transformations!

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.