[Editorial] Day of the Woman: A Feminist Look at I Spit On Your Grave

Trigger Warning: This editorial contains close discussion of rape and sexual assault

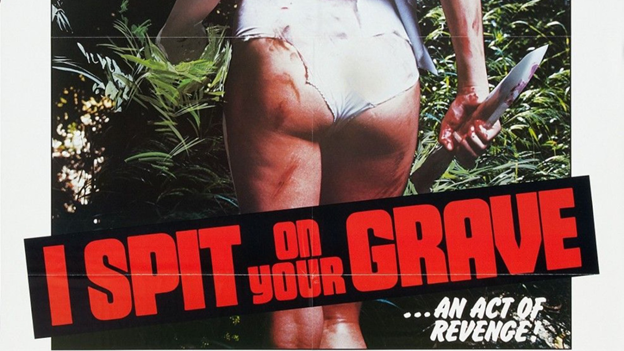

Few films have generated as much controversy as Meir Zarchi’s 1978 film I Spit on Your Grave, originally titled Day of the Woman. The film’s plot is quite simple—Jennifer Hills, a writer of women’s fiction, rents a cabin in the country for the summer and is gang-raped by four local rednecks.

“After recovering from her injuries, Jennifer proceeds to kill the rapists in a variety of gruesome ways, using their own tools and twisted ideologies against them. At the end of the film, she leaves the site of the killings behind without feeling remorse or facing punishment for her murders. The film remains disturbing due to the fact that the rape scenes sprawl over 25 minutes of the runtime, and also because these scenes feel too real. I Spit on Your Grave is shot in a quasi-documentary style; its scenes play in disturbing real- time, bereft of flashy camerawork and extradiegetic music; the unflinching eye of the camera never looks away from the violence and its aftermath, and instead assaults the viewer with its gaze, offering no easy out, no fade-to-black, and no mercy.” ¹

Rather than being made as the result of voyeuristic motivation, this scene was inspired by a real incident that occurred in 1974. In the director’s commentary on the 2002 DVD re- release, Meir Zarchi recalls that while driving past a park in New York City, he and his friend Alex Pfau saw a woman, “18 or 19 years old, totally naked, staggering toward us like a walking corpse . . . her body stained with blood and mud, her eyes wide open, staring into space and numb with shock.” The woman had been gang-raped for several hours. Zarchi and Pfau helped the woman into the car, and the three decided to report the incident to the police before going to the hospital.

Zarchi quickly realized how wrong that decision was. The officer on duty acted annoyed and indifferent toward the victim, hammered her with questions that were both insensitive and irrelevant, and completely ignored her need for medical attention. While witnessing this seemingly interminable session, Zarchi came to the sad realization that “the raping of the girl had not stopped, it had just been transferred from that park into this police station and was continuing in front of my eyes.” To Zarchi’s knowledge, no arrests were ever made. Hence, one may argue that the movie is an attempt to rewrite reality and create an ending of retribution of sorts for the rape victim without the manifold perils and pitfalls of police involvement.

The majority of film critics did not appreciate what Zarchi intended to accomplish with the film. With the exception of drive-in critic Joe Bob Briggs (who later provided a commentary track for the film’s 2002 DVD release), most critics were swift to condemn the film. Roger Ebert called I Spit on Your Grave a “vile piece of garbage,” and further stated that the movie was “so sick, reprehensible and contemptible that I can hardly believe it's playing in respectable theaters, [. . .] But it is. Attending it was one of the most depressing experiences of my life. [. . .] There is no reason to see this movie except to be entertained by the sight of sadism and suffering.”² The film was subsequently pulled from theaters prematurely and also became a centerpiece of the UK’s “video nasties” debate in the early 1980s. ³

The swift condemnation of the film by major critics may have killed its theatrical run, but likely contributed to its popularity in home video formats. The authors of this essay discovered the film decades after its initial theatrical release, thanks to finding it on VHS in mom-and-pop video rental stores. The first time Candy saw I Spit on Your Grave, she was 19 years old and had acquired it through the small video store she managed and knew nothing of the plot, only that it was both hated and loved and tremendously infamous. It was a title that could not be kept in stock in the store as, the first time it was rented, it was never returned. After this happened many times, Candy re-ordered a copy strictly for her to rent and went home to the houseful of people she lived with watch it. The house was full of young men in metal bands, friends of her musician boyfriend at the time, and they decided to stick around and watch the film with her, unbidden.

HAVE YOU LISTENED TO OUR PODCAST YET?

Candy says, “As the film played out, the men in the room cheered on the gang rape scenes. I literally felt like I was going to faint and began to dissociate as I was in the room with my current sexual abuser and, unbeknownst to me at the time, with my future rapist - a friend of my then-boyfriend that I would marry in a few years. He raped me so brutally and frequently that I considered suicide. I was 3 weeks late with my period during the time of that first viewing, rather sure I was pregnant (I was, it turned out), and the screen was showing something so relatable that I couldn’t handle it at the time and I wished I could disappear. I only managed to stay coherent through the movie by pinching my earlobe, something I heard could keep a person from fainting. My fingers were bloody when I let go”. Candy never watched the film again until she was 41 years old for the Ghouls Night Out feminist portion of her horror podcast The House That Screams, this time as a fan and a fierce feminist who felt catharsis and healing through the film.

Erica discovered I Spit on Your Grave when she was 22 years old and working on her undergraduate degree. She didn’t know quite what to expect when she found it on the shelves of a local mom-and-pop VHS rental store, but knew that it was infamous for its explicit violence. Erica says, “I was shell shocked by the time I finished the film. After years of casual sexual harassment from complete strangers as well as by men in my church, university, and larger community, I Spit on Your Grave spoke deeply to my own anxieties as a woman, and validated them as well. I felt exhilarated by the revenge scenes, and it made me contemplate the fact that women have options other than being passive victims.” I Spit on Your Grave inspired Erica to become involved with her local rape crisis hotline and to work as a victim advocate for her local Sexual Assault Response Team. She also later became friends with the film’s lead actress, Camille Keaton, and the two have remained in contact via phone and text for the last eight years.

I Spit on Your Grave has had its own belated revenge. After being trashed by critics upon its release, re-evaluation by academic theorists and film historians was long overdue. Marco Starr was perhaps the first to argue in the film’s favor. In his essay “J. Hills Is Alive: A Defense of I Spit on Your Grave”, he stated that the film is “actually a very good movie—well made, interestingly written, beautifully photographed and intelligently directed.”⁴ In her seminal 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws, Carol J. Clover devoted an entire chapter to deconstructing I Spit on Your Grave ⁵, and in 2018, David Maguire penned an entire book devoted to the analysis of the film and its legacy.⁶

Indeed, it appears that I Spit on Your Grave has flourished in spite of, or perhaps because of its early infamy and condemnation. To date, the film has spawned at least one unofficial sequel (1993’s Savage Vengeance, in which Camille Keaton reprises her role as Jennifer), an official though belated sequel directed by Meir Zarchi (I Spit on Your Grave: Déjà vu, released in 2018), a 2010 reboot (which itself spawned two sequels), a documentary (Growing Up with I Spit on Your Grave), and several imitators (I Spit on Your Corpse, I Piss on Your Grave; I’ll Kill You…I’ll Bury You…I’ll Spit on Your Grave Too!; and many others).

One of the most burning questions about the film remains to this very day remains: Is I Spit on Your Grave a feminist film? Feminists of all waves have been split since 1978. Some feel it glorifies rape and others feel it is a cathartic experience that does the opposite. With the history behind the film, Zarchi’s entire reason for the creation of the movie, and the film’s original title Day of the Woman (it was altered to fit in with other exploitation films such as I Drink Your Blood (1970) and I Eat Your Skin (1971)) to I Spit on Your Grave), both Candy and Erica feel that it is indeed a feminist film. You can find their thoughts on their feminist horror review section of their podcast The House That Screams here: Ghouls Night Out: I Spit on Your Grave. As written so poignantly in Diabolique Magazine, “Meir Zarchi achieved what he set out to do in I Spit on Your Grave, with uncompromising brutal simplicity. […] this metaphorical assault vehicle represents the breaking of shackles from male oppression and their sexual using of females - feminist revenge exploitation.” ⁷

Modern feminism is slightly confused by the picketing in the late 1970s and 80’s and the recalcitrance over the film that, in fact, turns the traditional male gaze into the female gaze so effectively. This is still a film that is hotly debated and largely avoided out of fear - even in the modern horror community - due to the sensitive subject matter. The revulsion one feels upon viewing the film - that instinctual fear of the subject matter - is indeed intentional. This is not the typical exploitation film, but rather a realistic look at the horrors of sexual assault and one strong woman weaponizing it against her attackers in a world where women are taught to yell “FIRE!” instead of “HELP!” as the average person wants to look the other way and NOT help. They are simply too afraid to get involved. Candy and Erica urge readers to review this film and seek out information on not just rape statistics, but how rapists rarely get convicted or more than a “slap on the wrists” for the toxic “boys will be boys” mentality still prevalent in today’s society. Candy knows, as someone haunted by her own experiences with rape, that she will battle it for the rest of her life through drug treatment and intensive therapy, and Erica knows from her work with rape crisis counseling that these women fall through the cracks of the system so frequently that these cracks are more chasms.

——

¹ Wright, Erica L. (2010). “Carnage and Carnality: Gender and Corporeality in the Modern Horror Film” in No Limits: A Journal of Women’s and Gender Studies, vol. 1 issue 1.

² Ebert, Roger. (July 16. 1980). “I Spit on Your Grave” < https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/i-spit-on-your-grave-1980> [accessed 6/04/2022]

³ Starr, Marco. (1984). “J. Hills is Alive: A Defense of I Spit on Your Grave,” in The Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media, Martin Baker, ed., London and Sydney: Pluto Press, 48-55.

⁴ In The Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media, Martin Baker, ed., London and Sydney: Pluto Press, 49

⁵ Clover, Carol J. (1992). Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.

⁶ Maguire, David. (2018). Cultographies: I Spit on Your Grave. New York: Wallflower Press.

⁷ Jones, Dave J. (May 2019). “Day of the Woman: Feminist Revenge Exploitation in I Spit on Your Grave” in Diabolique Magazine. < https://diaboliquemagazine.com/day-of-the-woman-feminist-revenge-exploitation-in-i-spit-on-your-grave-1978/> [accessed 6/04/2022].

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Bay (2012) with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Amber T](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684751617262-6K18IE7AO805SFPV0MFZ/The+Bay+website+image.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682536446302-I2Y5IP19GUBXGWY0T85V/picnic+at+hanging+rock.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Psychotic Women in Horror with Zoë Rose Smith & Mary Wild](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678635495097-X9TXM86VQDWCQXCP9E2L/Copy+of+Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Nekromantik with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677422649033-Z4HHPKPLUPIDO38MQELK/feb+member+podcast.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 5 & Wrap-up with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841326335-WER2JXX7WP6PO8JM9WB2/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%284%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 3 & 4 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841151148-U152EBCTCOP4MP9VNE70/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%283%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 1 & 2 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841181605-5JOOW88EDHGQUXSRHVEF/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841247731-65K0JKNC45PJE9VZH5SB/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] A Serbian Film with Rebecca and Zoë](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841382382-RY0U5K7XD4SQSTXL2D14/PODCAST+BONUS+2023.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)