[Editorial] Excision: Devotion to The Bloody Self

Tormented characters that excise the mundane from their internal person without camouflaging their anomalies enlighten our curiosities and caress cinema with a delightfully tainted exhibition of what true horrors can lie underneath ugly surfaces. Whilst beautiful objects appeal to the eye, the notion of blemished souls remains soothing as they appease our dark desires and repressed naturalness, and although stomachs are churned and spines become tingled, Excision is a forcefully welcomed film that leaves a mark on the viewer like a gaping wound.

Richard Bates Jr. lived out possibly every film student's dream as his short film of the same name (2008) soared through film festivals like a riptide, soon gaining enough attention to become a full feature length film. With countless nights and independent financiers came 2012’s most standout film of the year starring AnnaLynne McCord, Traci Lords, Ariel Winter, Roger Bart, with cameos from John Waters, Ray Wise, and Malcolm McDowell.

Excision follows the tumultuous life of Pauline (McCord), a megalomaniac struggling to assimilate her growing infatuation with the macabre whilst battling her pompous mother Phyllis (Lords), who emotionally renounces Pauline in favour of caring for her other daughter Grace (Winter) who is suffering from Cystic Fibrosis. In response to years of indifference to her environment, Pauline becomes increasingly unhinged, threatening the established pecking order.

Becoming indoctrinated by the symbolic order of acceptable abjectness is a standard practice in the ill fated condition of society. Women are required to possess impossible souls. Be sexually available to soothe lustful desires, but don’t flaunt it otherwise you are a whore. Never wear too much makeup, (boys are not attracted to it), but don't let your natural skin show. It's an endless, menacing cycle of torment that is rather aggressively dictated by commercial media and authoritative figures. The macabreness that reveals itself through the other does not just apply in menstrual werewolves, vengeful witches, and telekinesis prom queens, the other is ingrained within every mortal being. However, due to narcissistic hegemonies and phallocentric rulings, the gritty, dirty, and perverted self is refused exposure, instead of freedom they are rejected.

Excision radiates a shameless manifesto that thrives in the abject, unravelling Pauline’s gross demeanour to provoke solidified fears rife amongst adolescents. Simultaneously her sense of otherness is a force to be fearful of, disgusted even, whilst also establishing an alluring prowess impactful enough to force an underlying subconscious feeling of familiarity. Her acne-ridden skin oozes pus from the inflamed blemishes, and although the crimson dots strewn across her face are beyond normal, an internal alarm is triggered thanks to established microcosms of beauty standards declaring imperfections as disgraceful. The chokehold that beautified hierarchies have on pubescent females (particularly within an educational setting) is profound, with bullying and abhorrent behaviour to peers being deemed acceptable and part of the toxic process into adulthood. Pauline's embracement of flaws, or lack of care, directly disrupts the positional barriers of the symbolic order, therefore reconditioning the stability found within strict societal ideologies, solidifying the expression that it’s okay to be yourself, and not to worry about grossly impossible standards.

Pauline’s interactions with the everyday are startlingly obscure. The average day in her household externally replicates a scene of harmony, wealth, and an impassioned connection with archetypal family values. Yet, lying amidst the false smiles is a seedy underbelly where Pauline’s father sits mindfully unaware of the emotive infrastructure collapsing around him, her sister awaits in pain at her probable death, and her mother is a smotherer, at ease with being indicative and vain to save face for fellow white picket fence neighbours. The true willingness to be nothing more than a trophy child hangs heavy on Pauline’s shoulders. Between their mother-daughter bond there is an evil parasite that feasts on their dissimilarity. Phyllis continuously forces Pauline to attend cotillion classes to amend her boyish behaviour, as well as weekly improvised therapy sessions with Pastor William (wittingly played by self-acclaimed trash king John Waters) who dangerously undermines her capacities of creating harm in the near future. The conservative beliefs expressed by both William and Phyllis frame an institute built on top of fragile ground. Just as Grace needs biological assistance due to her condition, Pauline too needs drastic psychological first aid. This abandonment and maternal ambiguity have been an ongoing practice for the duo, concretising Pauline’s willingness to ascend to a higher level above Phyllis’s demanding standards, paving deadly destruction and turmoil on her way up.

The burgeoning fear experienced by those Pauline repels aligns her as a textbook misfit. Her life is a dormant pit, void of warmth and needed compassion. The only essence of companionship felt is with her ailing sister Grace. The theoretical paradox surrounding beastial women is reliant upon the mistreatment of normalised behavioural dynamics; if one were to rebel then they would succumb to illness, death, or a dreaded conviction of endless misery à la Alexia (Ella Rumpf) in Raw (2016), who eventually ends up in solitary confinement with no chance to feast upon her desires. In Excision, Pauline willingly continues to broadcast her loathsome pathology knowing that the probable punishment of isolation only opens the door for her self-devotion to flourish without any interruptions.

HAVE YOU LISTENED TO OUR PODCAST YET?

On the other hand, Grace is studious, simple, and a staple for eloquence, with Phyllis always favouring her poised manner over Pauline’s. However, per Excision’s disposition to survey less frequented expectations, it's Grace who suffers, dying at the hands of her own body's rejection, succumbing to illness. Whereas Pauline’s habitual self-glorification is rewarded, prospering after every nonconforming line is crossed, gifting a salacious invitation to act upon feral cravings, thus releasing purely satisfying lechery regardless of whether it defies patriarchal rulings.

Advancing Pauline’s impassioned wants is the overarching prognosis that her peers, parents, and authoritative figures are equated to being ‘less than’, not worthy of respect or basic human decency. As Excision's events escalate, Pauline’s conceitedness matures in a scene rarely explored in common cinematic territory. In an ungraceful attempt to disavow Pauline from the norm, she is explicitly shown pulling out her tampon, raising it to her nose to smell her excess as it hangs dangling clots, and dripping thick dark menstrual blood, resulting in obvious disturbance, and a strange catharsis over witnessing a prop so wrongfully tabooed, even in the brazen horror genre. The grotesque fascination is only continued in Excision’s dream sequences whose bloodshed rivals massacre-style films.

Pauline’s abjectness translates into a forcefield where normalised Freudian slips become full-on Freudian mudslides, lacking the typical juggling with shame and guilt to repress alternative identities. Excision is motivated by her very aware and assured knowledge that she does not conform to the normalised beauty standards, nor does her personality match that of the average insecure teenage girl. Instead, her euphoric response in being gross is akin to a fetish that fuels a sexualised flame deep inside of her psyche. Bates Jr. makes the synchronisation clear, the more revolting Pauline is, the more power she obtains, like a repugnant mosquito sucking the disgust out of its victim. Rather boldly, Pauline puts herself first; unabashedly adoring her own depravity and complete atypical presence. Throughout the film, her passion remains devoted to her pleasures, needs, and lusty wants – and rightly so. In typical Pauline fashion, she not only decides to lose her virginity whilst on her period, but she also chooses the most popular boy in school, Adam (Jeremy Sumpter) as her plaything. Bates Jr. fashions the bloody sex scene between the two in such an impassioned yet vulgar manner where she takes charge. Instead of Adam demanding oral sex, it’s Pauline who pushes his head down towards her menstruating vagina comically leaving Adam unbeknownst with a blood-strewn face. During sex Pauline grabs the bull by the horns and straddles Adam. As she sits upon him, her head raises to the ceiling as if looking up at the heavens that her mother forces her to believe in, defying every aspect of chastity and saintliness. Typically, when a woman decides to cash in her virginity, it ends up being a moral lesson resulting in unwanted force, pregnancy, or a sexually transmitted infection. In Excision, Pauline’s fall into carnality acts like a currency, fuelling her hankering for mayhem.

Adam is her thrown and her crown is the pleasure deviated from polluting the normalised sexual hierarchy.

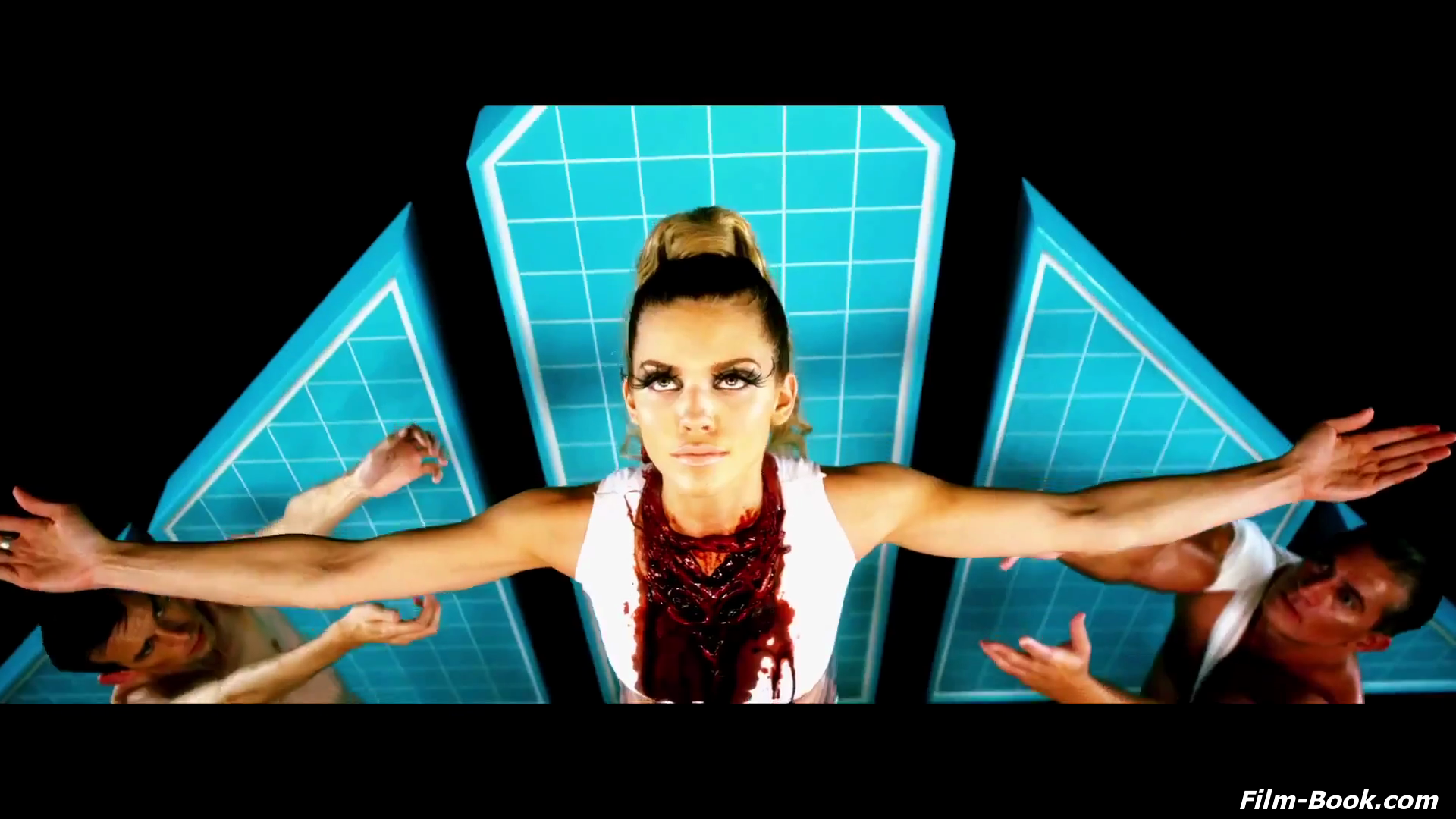

Pauline’s journey began with psychosexual dreams that defied any moral principles she may possess, instead of romantic dreams of a prince charming, her slumber visuals were ridden with a bouquet of necrophilia, cannibalism, and venereal impulses. Within cinema the body is a vehicle, an immersive instrument, leaving trauma in its wake as a consequence of whatever excessive corporeality it explores. In Pauline’s fantasies, a methodological aesthetic is utilised in which clinical white tiled environments are juxtaposed against the viscera splattered walls. And it's within these environments where Pauline strips away whatever humanity she has in favour of concocting tales ridden with bulbous, fleshy perversions such as yanking a new-born baby straight from her womb before placing it into a rusted microwave, orgasming over the child's explosion.

The utterly sinful but beguiling imagery Bates Jr. exhibits throughout these dream sequences begins to slip out of her subconscious and into the real, emulating her desires through tampon sniffing, self-mutilation, dissecting animals and then losing her virginity in an unconventional manner. Pauline’s toxicity has lost its self-governing harness, her means to explore nihilistic prospects is unleashed and in the wild, submitting her surrounding landscapes to a spectral of psychological torment and fatalistic dread.

Amongst the peppered barbarism, Pauline exhibits an unorthodox soft side, less akin to real emotion, and more like an understanding of how she is ‘supposed’ to feel. She routinely prays to God, not seeking religious prospects, but instead to reflect upon her moral wishes if He were to be listening. As the film continues, Bates Jr. imparts revelation upon Pauline’s worshipping of the macabre. It is amidst these prayers where her love for Grace is proven and hatred for her mother is brutally exercised, with her asking God to save Grace, and that He would be doing her a solid by banishing Phyllis. Her cruel deflection towards religion, something that her mother forces upon her, is a purposeful tool that she uses to shock, thus controlling her interactions with those around her. They can be revolted and furious at her very presence, but only under her terms.

Pauline’s knowledge of her existentialism is a feisty facet placing a masochistic frame around her actions, in turn convincing the viewer that their own abjection and innate connection with otherness is acceptable, pleasurable even. Horror sets up an environment for marginalised beings to come together and stand proud of their visceral prowess. Excision shines in the elixir of fleshy moral codes, nourished flaws, and disfigured eroticism to paint a cathartic narrative that says it's okay to be different, to crave the bold release that resides within abjectness.

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Bay (2012) with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Amber T](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684751617262-6K18IE7AO805SFPV0MFZ/The+Bay+website+image.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682536446302-I2Y5IP19GUBXGWY0T85V/picnic+at+hanging+rock.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Psychotic Women in Horror with Zoë Rose Smith & Mary Wild](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678635495097-X9TXM86VQDWCQXCP9E2L/Copy+of+Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Nekromantik with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677422649033-Z4HHPKPLUPIDO38MQELK/feb+member+podcast.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 5 & Wrap-up with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841326335-WER2JXX7WP6PO8JM9WB2/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%284%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 3 & 4 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841151148-U152EBCTCOP4MP9VNE70/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%283%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 1 & 2 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841181605-5JOOW88EDHGQUXSRHVEF/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841247731-65K0JKNC45PJE9VZH5SB/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] A Serbian Film with Rebecca and Zoë](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841382382-RY0U5K7XD4SQSTXL2D14/PODCAST+BONUS+2023.jpg)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)