[For The Love Of Franchises] How Scream Changed the Representation of the Final Girl

The slasher genre has married gore and sexuality in an unholy bond that has remained strong since its inception.

The roots of the slasher film began in Italian giallo films of the 1960s and 1970s, well known for their innovative use of violence, gore, and sexuality in their murder mystery narratives.

These films reflected the freedom of expression in the realms of sex, including female sexuality and homosexuality, that were coming out of the closet and into the mainstream during the time.

However, as the genre developed, notably with the release of Tobe Hooper’s iconic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in 1974 and Mario Bava’s Bay Of Blood three years previous, we start to see very different codes and conventions forming.

These films, often cited as the foundations of the slasher genre, established the codes and conventions of near-indestructible serial killers, often driven by revenge, stalking attractive young girls guilty of actions they believe they must be punished for.

Thus began the influx of sex and violence within slasher films, often leading to the mutilation of women that became a common trope within the genre.

Laura Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze rose to prominence, in which she speculated that female characters on screen were coded solely to be looked at by both the audience and the male characters on screen who were the bearers of the gaze, created by the cinematic experience that places the viewer in a masculine subject position.

While the slasher genre, and horror as a whole, subverted the idea of societal norms though its representations, these same characters were punished for their transgressions such as challenging the idea of heterosexuality or pre-marital sex.

In terms of the representation of women, many slasher films arguably repressed female characters and condemned the idea of the ‘new woman’ in society at large, reinforcing traditional gender roles by showing female characters being punished by male antagonists.

In The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, we follow the journey of a group of teenagers on a road trip as they are tortured and killed one by one, apart from one female protagonist, Sally (Marilyn Burns), who survives.

She does this by refuting stereotypical femininity and sexuality to survive the retribution that her sexually active and feminine friends receive.

Ultimately, although Sally escapes antagonist Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) and the Sawyer family she is saved by a male driving a truck who allows her to escape, which further confirms the idea that women within the narrative are subjugated to men.

Following this, the release of Halloween in 1978 propelled slasher films into the mainstream, becoming one of the highest-grossing independent films of all-time that led to a boom in the genre.

It further solidified the template for making a slasher film, consolidating the idea of the ‘final girl’, the last woman left alive to confront the killer at the end of the film.

While this can be seen as positive female representation, many final girls of the 70s slasher era adopted masculine qualities in order to survive their ordeals, while other women who embraced their femininity and sexuality were gruesomely killed.

Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) can be seen to be a strong female character as she defeats antagonist Michael Myers (Nick Castle), though she adopts masculine traits to achieve this via a masculine-coded costume and a unisex name, as well as being portrayed as virginal and innocent by abandoning her own sexuality and condemning the sexuality of other females in the narrative.

Women within Halloween, including Laurie, are objectified either through sexualisation or objectification.

Judith (Sandy Johnson), Annie (Nancy Kyes) and Lynda (P.J. Soles) are punished for their sexual promiscuity, whereas Laurie is used as a toy by Michael to be tortured both mentally and physically.

The success of Halloween led to its conventions being repeated in films such as Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street among others, ultimately leading to a lull in the genre as audiences became bored.

Then along came the slasher film that would turn the genre on its head.

Scream (1996) set out to pay tribute to slasher movies and take a retrospective look at the genre by both acknowledging the codes and conventions of the traditional slasher and subverting them.

Through its references to other films and their codes and conventions, Scream subverts them by directly addressing the inequality they bred while also giving female characters more autonomy, allowing them to become more resourceful, witty, and savvy than their predecessors.

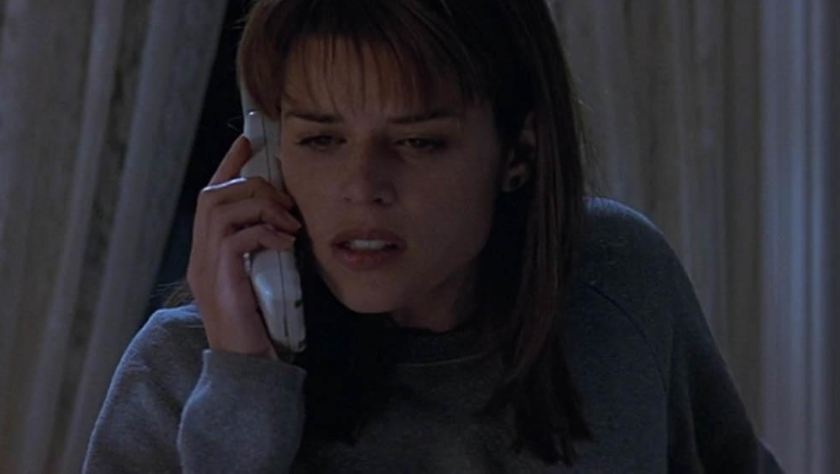

From the very opening scene of the film, we are thrown into a postmodern world that is self-referential and self-reflectional of the genre as a whole.

Protagonist Casey Becker (Drew Barrymore), who is home alone, is called by an anonymous antagonist, who begins questioning her about her favourite ‘scary movies’.

In response, she expresses an interest in films, and names Halloween as her favourite.

These metatextual references continue when antagonist Ghostface begins to torment Casey as she shouts, ‘who is there?’ to determine his location.

They reply, ‘Never say "who's there?" Don't you watch scary movies? It's a death wish. You might as well come out to investigate a strange noise or something.’

The iconic scene reflects the societal change that we are now more accustomed to in the study of film.

Though Casey is murdered by a male antagonist, the focus of her character is on her knowledge of films rather than her costume and body, and she is arguably not objectified within the scene by the viewer.

Her boyfriend, however, is seen from a high angle shot before his murder as if he is being looked down on and he is subservient to the killer. The use of this shows that gender is not a focus when victims are attacked as both men and women are subjected to the same violence.

Scream most notably rewrites the notion of the final girl, exploring themes of subverting the gender binary and notions of female sexuality.

Protagonist Sidney (Neve Campbell) can be seen to signify the stereotypical final girl of years gone by as she is not dressed in stereotypically feminine clothing, has a stereotypically masculine name akin to Laurie in Halloween, and obeys patriarchal law as she follows her father’s (Lawrence Hecht) rules regarding sexuality and remains virginal as the narrative begins.

However, when she is faced with the danger of a male antagonist she subverts the common conventions of the Final Girl and repeatedly challenges the idea of patriarchal rule by overpowering and outsmarting men.

A pivotal scene within the narrative in terms of conventions and representation occurs when Stu (Matthew Lillard) throws a house party in the wake of the murders committed by Ghostface after school has been closed to keep the students safe.

Within this scene Stu verbally addresses the codes and conventions of the slasher film and how to survive the narrative whilst watching Halloween by saying that: ‘Number one: you can never have sex. BIG NO NO! BIG NO NO! Sex equals death, okay? Number two: you can never drink or do drugs.’

Randy (Jamie Kennedy) goes on to say: ‘The sin factor! It's a sin. It's an extension of number one. And number three: never, ever, ever under any circumstances say, "I'll be right back." Because you won't be back’

Following this self-reflexive quote, Sidney, and her boyfriend Billy (Skeet Ulrich) engage in sexual intercourse at her instigation, and ultimately survives throughout the film and its subsequent sequels to face the killer each and every time.

Likewise, protagonist Gale Weathers (Courtney Cox), is depicted as a strong female character through her high-powered job in a male-dominated career path as a news anchor, and her cutthroat determination to get the information she needs from other characters, which also includes actively using her sexuality as a means to exert power over her male counterparts.

Both women maintain their femininity and exert power over patriarchy without having to adopt masculine traits or a phallic weapon when challenging their antagonists.

In the final scenes of the film, it is revealed that both Stu and Billy have been perpetrating the murders in order to both re-enact their favourite scary movies, and to avenge Billy’s parents as it was Sidney’s mother who had an affair with his father that destroyed his family life.

This can be seen as chastising female sexuality as the victims have been punished for the sexuality of a female, though it can also be seen that female characters dominate the narrative as the killings are triggered and controlled by female power.

Gender and power roles are further subverted when it is revealed that Sidney’s father has been captured by the pair and will be framed for their murders, so it is up to Sidney to save her father in the role as a damsel in distress.

As Billy and Stu stab each other to make their deception convincing it can be argued that gender norms are subverted as the repeated penetration of each other and pleasure they show has links to homosexuality and refutes the heterosexual norm that men had been stereotyped as within slasher films to this point.

Contrastingly, Sidney and Gale do not adopt the traditional knife to kill their antagonists; Stu is killed by a TV crushing his head and is metaphorically killed by his passion for slasher films as he forgets the conventions he has rigidly stuck to and allows himself to be overpowered by a female protagonist, and Gale shoots Billy as he attempts to kill Sidney.

The women stand over the bodies of their antagonists and are framed in a low angle shot which holds connotations of power and strength, further solidifying their status as postmodern heroes within the genre.

Following the first film, Scream spawned an entire franchise that continued to revolutionise the representation of women within slasher films.

Sidney continues to survive the franchise, not because she adheres to the ‘good girl’ stereotype, but because she utilises her smarts and ability to adapt to and analyse each dangerous situation.

Gale doesn’t just survive the franchise; she thrives as she outwits each new Ghostface killer and her career goes from strength to strength.

Though her strength does not mean she does not show an emotional side, as in Scream 2 she admits her strong feelings towards Officer Riley.

We are even treated to diverse, strong female characters within the series in the form of female antagonists.

Mrs. Loomis (Laurie Metcalf) and Jill Roberts (Emma Roberts) appear in Scream 2 and Scream 4 respectively as the films’ deranged killers.

They forced Sidney to evolve and adapt to survive their meticulous murder sprees as they challenged all of her preconceptions about the Ghostface killer.

The fifth Scream film sees Sidney and Gale take a step back so two new final girls can take on the Ghostface killer - Tara (Jenna Ortega) and Sam (Melissa Barrera).

Both are Latina women who embrace their femininity, sexuality, and smarts unashamedly - something that sees Tara survive the film’s brutal opening scenes, which Casey and her other predecessors could not do.

Sam further deconstructs the final girl trope as she is the child of former Ghostface killer Billy Loomis, with the narrative of the film focussing on the girls overcoming their dark past and fractured relationship with each other and Woodsboro as a whole to overcome their antagonist.

The film also includes Mindy (Jasmin Savoy Brown), the niece of Randy Meeks, who is a first for the franchise as a biracial, queer character who survives until the end of the film, assisting the other central characters with her in-depth knowledge of the slasher genre - sound familiar?

The rejuvenation of the slasher since Scream saw a vast change in the way women were portrayed.

While misogyny and sexualisation is still present within horror, Scream not only revitalised the slasher genre, it reinvigorated its codes and conventions to better reflect the ever-changing themes of femininity and masculinity in its beloved characters and tongue-in-cheek narrative that makes the film every bit as iconic today as it was when it was released.

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)