[Editorial] Junji Ito, Monthly Halloween and the Rise of Shojo Horror

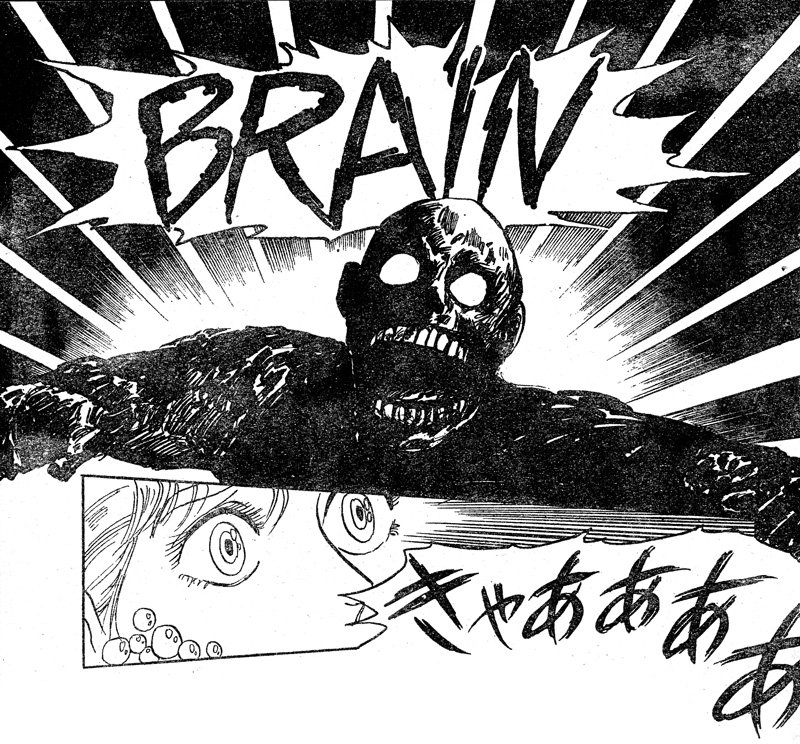

Junji Ito is perhaps one of the most well-known horror mangaka (manga artists) in the Western world these days. With a style that is equal parts stomach-churningly hideous and beautifully detailed, you dread each turn of the page but also want to spend time to gaze at the minutiae of his work.

His works have been adapted into film and anime several times to varying degrees of success, with a new anime adaptation of his work Uzumaki, about a small town that becomes consumed with an obsession for spirals, currently in production. Yet it might surprise you to learn that most of Ito’s work debuted in a shōjo manga magazine by the name of Monthly Halloween.

Shōjo manga, or “girls manga” might bring to mind soft school girl romance stories with large eyed protagonists staring adoringly at a very pretty boy who may or may not be surrounded by either sparkles or flowers, titles like Fruits Basket or Ouran High School Host Club. However shōjo is more an indicator of demographic rather than specific genre and shōjo manga magazines and therefore can contain a variety of stories including horror. In Japan, manga chapters are typically released in magazines that come out weekly, bi-weekly, monthly, or bi-monthly, and later are collected into books called Tankōbon, which is what people in the west would be more familiar with as manga volumes. Whilst shōjo is a demographic rather than a genre, there are certain ingredients that are often seen whatever the content of the story; softness to the art style, female protagonists, coming of age themes, an emphasis on youth and beauty, and a school setting are all very common, and a shōjo horror story tends to use those themes but turn them sinister.

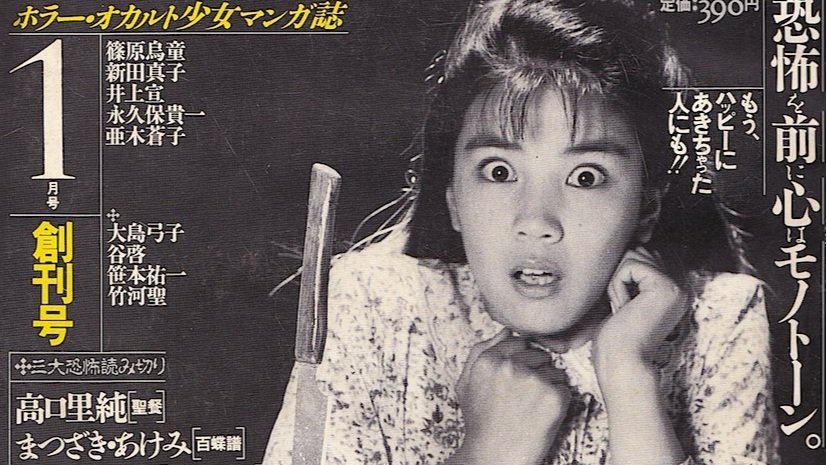

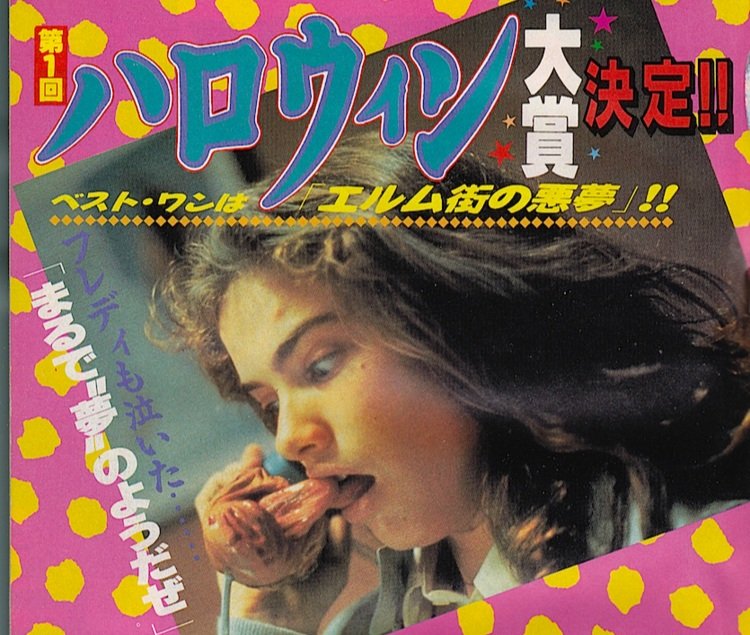

Monthly Halloween was the first all-horror shōjo manga magazine, released by Asahi Sonorama. It began publication on (Friday) 13th December 1985, a response to the growing popularity of Western horror movies in Japan at the time amongst teenage girls. Involved in the launch of the publication was Kazuo Umezu. Umezu is unfortunately not as well known as some other mangaka, but his career has spanned sixty years and his Drifting Classroom is a twisted story of elementary school children transported to a desolate future and needing to survive, think Lord of the Flies with shades of Terminator. He started the Kazuo Umezu Prize, an initiative to scout out new manga talent. It was the first of these that Junji Ito won with Tomie, and the rest is horror manga history. The first Tomie story is about the titular teenage girl who, after being murdered and dismembered, turns up the next day to school as if nothing happened, much to the terror of her classmates and teacher. In terms of quality it’s rough, but you can see the groundwork that Ito would develop in future stories with the character. Tomie became a figure of twisted and manipulative beauty mixed with the physical horror of how whenever she is dismembered, each piece of her grows into a fully formed Tomie who goes out and begins the cycle again. One of the most memorable moments in the series is the one that stuck with me as a teen; when a Tomie has been killed and upon being taken to a hospital her kidney is used in a life saving operation, but the patient’s stomach starts swelling, as if something is growing inside…

In total, 11 chapters of Tomie were published in Monthly Halloween, before moving to the magazine’s sister publication Nemuki, short for Nemurenu Yoru no Kimyō Na Hanashi “Strange Stories for Sleepless Nights”, which aimed to be a bit more mature in its stories than Monthly Halloween. Other memorable short Ito stories which were published in the magazine include Hanging Balloons, where people are stalked by grotesque balloons with their own faces on them, and Dying Young, a story of young girls who contract a disease that gives them beauty at the cost of their lives.

HAVE YOU LISTENED TO OUR PODCAST YET?

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

Alongside serialised manga, Monthly Halloween would feature articles related to the occult and horror movies; ghost photos, reader ghost stories, special effects features, and instructions on how to perform Kokkuri-san (a kind of Japanese Ouija board). There was also a very interesting curiosity; manga adaptations of Western horror movies, including A Nightmare on Elm Street, Return of the Living Dead, and Re-Animator. Alterations were made to the stories, possibly due to limited space, to help them fit r a Japanese audience better, or to encourage readers to see the actual film for themselves. In any case, seeing Nancy defeat Freddy through the power of prayer was quite the alternate ending.

One of the best things about Monthly Halloween though, was the covers. Whilst towards the end they would have the more typical covers featuring drawn artwork, including Junji Ito’s, for most of the magazine’s run they would have young models in various horror scenarios. What I enjoy most about these is the variety, the combination of very Western derived horror tropes such as masked killers and even some characters like Freddy Kruger or Belial from Basket Case, and more traditional Japanese horror elements like yōkai (folkloric creatures), yūrei (spirits) or things like Gakkou no Kaidan (School Ghost Stories). There is an enjoyably camp quality to them, an element of fun that brings to mind a film like Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House, which whilst adapted as a shōnen (boys) manga at the time of the film’s release does have a lot of the factors familiar to shōjo; female friendship focussed story, themes of coming of age, that would fit very nicely alongside other examples of shōjo horror.

Monthly Halloween ceased publication in 1995. The possible reasons for this include financial, as the early nineties saw a burst in the economic bubble of the 80s in Japan, and a waning lack of interest in horror due to certain real-world events such as the Tokyo Subway Sarin gas attack of early 1995 which caused widespread social anxiety, and the crimes of Tsutomu Miyazaki, the “Otaku Killer”, which led to a degree of moral panic over both geek culture and horror movies in Japan. The overall effect on horror in Japan was one of stagnation and would not see any real progression arguably until Hideo Nakata’s Ring in 1998.

Whilst shōjo horror does live on in other publications, Monthly Halloween remains a beautiful celebration of female horror fandom with pure enthusiasm for the genre.

RELATED ARTICLES

Strap in folks, because the aliens have landed and they’re here to probe, eviscerate, procreate, and replace…

While some films successfully opt to leave the transformation scene out completely, like the wonderful Dog Soldiers (2002), those who decide to include it need to make sure they get it right, or it can kill the whole vibe of the film. So load up on silver bullets, mark your calendar for the next full moon, and check out 11 of the best werewolf transformations!

Let’s take a look at nine of the most amazing antler deaths in horror!

The slasher sub genre has always been huge in the world of horror, but after the ‘70s and ‘80s introduced classic characters like Freddy Krueger, Michael Myers, Leatherface, and Jason, it’s not harsh to say that the ‘90s was slightly lacking in the icon department.

Being able to see into the future or back into the past is a superpower that a lot of us would like to have. And while it may seem cool, in horror movies it usually involves characters being sucked into terrifying situations as they try to save themselves or other people with the information they’ve gleaned in their visions.

Here are 9 home invasion horrors that will cause you to double check whether you’ve locked all your doors and windows.

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.

If you like cults, sacrificial parties, and lesbian undertones then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the book for you. Samantha, a student at a prestigious art university, feels isolated from her cliquey classmates, ‘the bunnies’.

I am a Shyamalan apologist. I would say I’m sorry but I’m really not. I know he has some questionable films and has made some unorthodox choices over the years when it comes to his twists, but the king of narrative spin still stands tall in my book.

In the six years since its release the Nintendo Switch has amassed an extensive catalogue of games, with everything from puzzle platformer games to cute farming sims to, uh, whatever Waifu Uncovered is.

EXPLORE

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.

In the six years since its release the Nintendo Switch has amassed an extensive catalogue of games, with everything from puzzle platformer games to cute farming sims to, uh, whatever Waifu Uncovered is.

A Quiet Place (2018) opens 89 days after a race of extremely sound-sensitive creatures show up on Earth, perhaps from an exterritorial source. If you make any noise, even the slightest sound, you’re likely to be pounced upon by these extremely strong and staggeringly fast creatures and suffer a brutal death.

If you like cults, sacrificial parties, and lesbian undertones then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the book for you. Samantha, a student at a prestigious art university, feels isolated from her cliquey classmates, ‘the bunnies’.

The slasher sub genre has always been huge in the world of horror, but after the ‘70s and ‘80s introduced classic characters like Freddy Krueger, Michael Myers, Leatherface, and Jason, it’s not harsh to say that the ‘90s was slightly lacking in the icon department.

Mother is God in the eyes of a child, and it seems God has abandoned the town of Silent Hill. Silent Hill is not a place you want to visit.

Being able to see into the future or back into the past is a superpower that a lot of us would like to have. And while it may seem cool, in horror movies it usually involves characters being sucked into terrifying situations as they try to save themselves or other people with the information they’ve gleaned in their visions.

Both the original Pet Sematary (1989) and its 2019 remake are stories about the way death and grief can affect people in different ways. And while the films centre on Louis Creed and his increasingly terrible decision-making process, there’s no doubt that the story wouldn’t pack the same punch or make the same sense without his wife, Rachel.

The story focuses on a group of survivors after most of the world’s population is wiped out by Captain Trips, a lethal super-flu. And while there are enough horrors to go around in a story like this, the real focus of King’s book is how those who survive react to the changing world around them.

While some films successfully opt to leave the transformation scene out completely, like the wonderful Dog Soldiers (2002), those who decide to include it need to make sure they get it right, or it can kill the whole vibe of the film. So load up on silver bullets, mark your calendar for the next full moon, and check out 11 of the best werewolf transformations!

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Bay (2012) with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Amber T](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684751617262-6K18IE7AO805SFPV0MFZ/The+Bay+website+image.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682536446302-I2Y5IP19GUBXGWY0T85V/picnic+at+hanging+rock.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Psychotic Women in Horror with Zoë Rose Smith & Mary Wild](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678635495097-X9TXM86VQDWCQXCP9E2L/Copy+of+Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Nekromantik with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677422649033-Z4HHPKPLUPIDO38MQELK/feb+member+podcast.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 5 & Wrap-up with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841326335-WER2JXX7WP6PO8JM9WB2/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%284%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 3 & 4 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841151148-U152EBCTCOP4MP9VNE70/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%283%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 1 & 2 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841181605-5JOOW88EDHGQUXSRHVEF/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841247731-65K0JKNC45PJE9VZH5SB/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] A Serbian Film with Rebecca and Zoë](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841382382-RY0U5K7XD4SQSTXL2D14/PODCAST+BONUS+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Aliens in Sci-Fi & Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685351258912-P3ETEO2CL7F54CS4QKX3/image12.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)

![[Editorial] The 9 Most Amazing Antler Deaths in Horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684065424643-3XDDCWVBM6CCQPXF4YTW/Image+2+%2840%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 of The Best Home Invasion Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1683913399685-G6Y54FFWUCL4CW6ISJB1/Image+1+%2841%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Ranking M. Night Shyamalan: his Good, his Bad, Not so Good, and his Twists](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687196229638-MMAFHN9EL2RXAEJO5G3B/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+18.21.53.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)