[Editorial] Mommy’s Busy: Punishing Maternal Ambition in The Swarm

I went back to work when my daughter was six weeks old. I’d hidden my pregnant bulge just beneath the bottom edge of the Zoom screen for months. My students had no idea that as we discussed Carol Clover’s take on rape revenge, the fetus was pressing on my bladder so hard I thought I would scream. I treated the birth, which landed miraculously at the start of Winter Break, like a bad case of food poisoning; nobody had to know. When I returned, I tilted the computer screen up and slid my wriggling child under the metal desk in my office, latching her to my breast. When she let out an errant cry, I forced a high-pitched laugh from my lips, very nearly covering the sound. When she farted, I scooted my chair against the tile floor abruptly. When she bit down on my nipple with her inexplicably sharp gums, I plastered a huge smile on my face to distract from the tears welling in my eyes. I learned early what every mother comes to know: Work and children do not mix.

She’s a toddler now, old enough to eat lamb chops off the bone and Velcro her shoes. As she grows, the problem of work grows too. When I finish writing this essay, I’ll drive forty miles to pick her up from her grandma’s house. As I type each word, I berate myself for taking those ten minutes to play Wordle. The traffic on the freeway will be my penance. When I walk into the house, my mother will scoop my daughter into her arms to greet me at the door. I’ll lean in to kiss my girl’s rosy little cheek, but she’ll quickly turn away, burying her face into Grandma’s shoulder. My mom will give me a guilty smile, and I’ll bend towards the small, upturned ear and whisper, “I’m sorry sweetie, but Mommy’s on a deadline.” She’ll turn to look me straight in the eyes and say “Da.” And I’ll know exactly what she means: You are a terrible mother. Again, work and children do not mix.

The bad mom is a trope that has existed in horror since the advent of the genre itself. From Norma Bates to Nola Carveth, the monstrous mother is a symbol of sexual deviance, cannibalistic impulses, and castration fantasies. The job of the horror film, and its audience in turn, is to delight in the punishment of this horrific woman, birthed of blood and bile. But motherhood looks different now than it used to. We no longer sit in our rocking chairs wrapped in moth-eaten floral blankets, dreaming of ways to fuck our sons and kill their mistresses. Now we have Mommy Influencers and sleep trainers and listicles in our inboxes. We also have not-so-whispered conversations about hating our kids sometimes and letting them cry just a little too long when they wake us up at 3am. Now we have jobs, and worse still, ambition. What is the modern horror film to do with this new picture of motherhood?

French filmmaker Just Philippot answers this question with his 2020 film La Nuée or The Swarm. The film’s protagonist is Virginie, a widow raising her teenage daughter and pre-teen son on a farm in rural France. In the wake of her husband’s death, Virginie has converted their goat farm into a locust farm, committed to introducing her community to a protein-rich food source in preparation for the inevitable food scarcity of climate change. The transition has not been an easy one. Virginie’s locusts are not reproducing quickly enough, her buyers are unwilling to pay a fair price, and her daughter Laura is bullied at school for her creepy crawly lunches. Virginie’s dedication to her locusts is tinged with desperation.

As she pipes classical music into the locust enclosures and delicately places homemade gelatin between their mandibles, Virginie’s quiet rage bubbles just beneath the surface. After one encounter too many with a miserly vendor, Virginie has had enough. Pulling a box cutter from her cutoff jeans, she slashes through her locust habitats and smashes their breeding cages. Attempting to pull the wooden frames apart with her bare hands, she slips and hits her head on the hard ground, falling into unconsciousness. She wakes to find her locusts lapping at the blood that pools beneath her. An unusually lively buzz fills the air.

As it turns out, Virginie has quite literally stumbled upon the secret to a thriving business model. Entering the locust enclosure the following day, Virginie discovers that it is teeming with new life. The locusts have begun to multiply at a shocking rate. Virginie’s momentary joy is eclipsed by a dark realization: her blood is the key to her locusts’ prosperity. Without hesitation, Virginie unravels the bandage concealing a large wound on her forearm sustained in her fall the night before. As she reaches her hand to unzip the mottled plastic sheeting of the locust habitat, a swarm of dark bodies surges toward her, just visible beyond the opaque barrier. She thrusts her arm inside, stifling a scream as the locusts begin their feast.

Virginie’s self-sacrifice produces the desired effect. Her lab now overflows with locusts, and her ambition grows in synchrony. She expands her business, broadens her client base, and begins to establish financial stability. However, Virginie’s act of maternal transference is not without consequence. As she feeds her adoptive children, her biological children begin to starve. Virginie’s son Gaston misses soccer practice while she is locked in the bathroom, plucking serrated leg burrs from her bleeding flesh with tweezers. Dinner goes unmade while she dreams up alternate sources of plasma. Laura must adopt the role of parent to Gaston while Virginie suckles her newborns. Of course, Virginie’s shift in priorities will not go unpunished.

In a sequence that perfectly illustrates the imbroglio of Virginie’s interspecies household, the family sits around the dinner table, Laura sullen and agitated. Laura implores her mother to explain why they can’t just sell the farm, the site of so much shared trauma. Virginie explains,

Virginie: It would mean we failed.

Laura: No. It would mean you failed…This place reeks of death.

V: You happy now?

L: Why the fuck are you doing this?

V: Why am I doing this? I’m doing it for you. You have to eat, go to school, buy clothes--

L: You don’t care about us! You don’t know what we do all day! You don’t know shit, so what--

V: Shut up!

We cut to a shot of Virginie inside the locust enclosure, bathed in eerie fluorescent green light, slicing her wrist open with a blade. She huddles on the floor, naked and crying, as the locusts surround her.

The double bind Virginie finds herself in is a precondition of motherhood, as inevitable as sleeplessness and diaper cream under your nails. No amount of sacrifice is sufficient when raising children; if you are succeeding in one aspect of your life, you are failing in another. Virginie’s choice, a non-choice really, to prioritize her family’s financial security, means that she is failing to adequately care for her children. But of course, the inverse would produce the same result. It’s enough to drive a girl crazy. And it does.

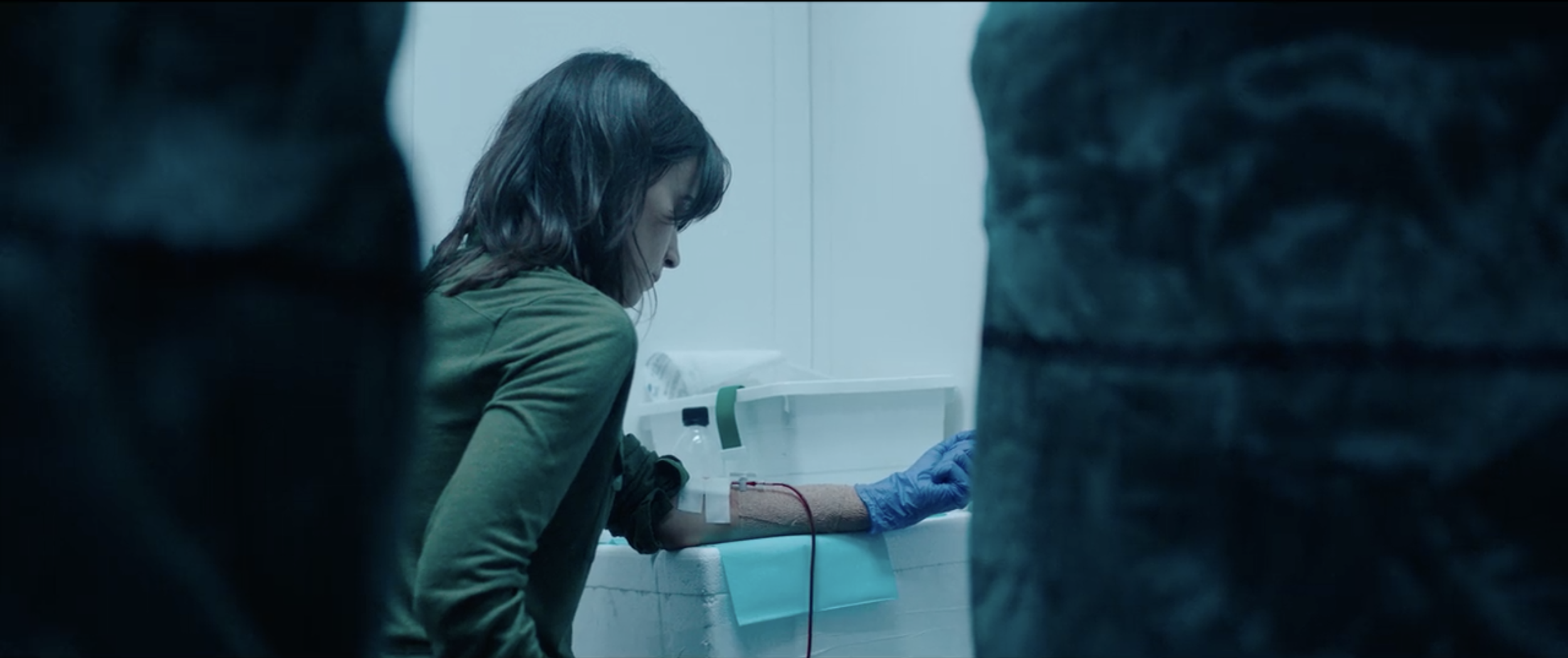

As the swarm of locusts grows, Virginie’s frequent blood sacrifices become unsustainable. She is literally drained, now hooking up lengths of plastic tubing directly into her veins, spilling her blood into industrial buckets. But when the locusts accidentally eat the family pet, Virginie gets a bright idea. Late one night, she lures the neighbor’s dog into the locust enclosure, emptying its blood into a bright neon kiddie pool. After the dog, she turns to the local farm animals. Virginie has discovered what so many working moms do: when you’ve wrung yourself dry, ditch breastfeeding and switch to formula.

The locust enclosures on Virginie’s farm multiply, domed structures dotting the land like so many pregnant stomachs. But as Virginie’s career flourishes, her family collapses. The cracks become craters when Virginie, exhausted from killing animals all night, fails to show up to wish Gaston farewell as he leaves for soccer camp. Laura must send him off alone, forced to cover for her mother’s glaring absence. She arrives home prepared to confront Virginie but finds a bloody pile of clothes instead. She makes her way outside, following the high-pitched whine of the locusts, and finds her mother wearing only underwear and a protective helmet, convulsing under a blanket of locusts. This is Laura’s primal scene, and her exclusion will not stand.

Laura confides in a family friend, Karim, who burns down Virginie’s locust enclosures. As the bloodthirsty locusts pour into the night sky and ravage Karim’s body, Laura flees to a nearby lake. She hides beneath an upturned boat as a cloud of locusts divebomb the hollow shell in a ceaseless attempt to reach her. As Laura screams for her mother, Virginie runs into the lake, pulls out a knife, and slices into the flesh of her arms. She coats her face in her own blood. The locusts subsume her. She slips beneath the surface of the water underneath a black undulating cloud. Laura swims toward the spot where her mother disappeared, pleading for her through tears. Virginie emerges from the water, broken and bleeding. Laura holds her close against her chest as a constellation of locusts dots the sunrise, in search of a new mother from which to feed.

Virginie’s sacrifice has finally found the correct object, the culturally sanctioned locus of maternal bloodletting. As she offers up her life for her daughter, instead of her locusts and the career they signify, Virginie is reborn. Cradled against her daughter’s breast, rising from the baptismal waters, Virginie is born again. A Good Mom.

The Swarm is available to stream on Netflix.

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.