[Editorial] Poetry, Literature, Fairy Tales and the Gothic in An American Werewolf in London (1981)

Whether it be the mist-covered expanses of the Yorkshire moors or in the confines of the back of a Hackney Taxicab, an American Werewolf in London (1981) is haunted by the past through its inclusion and allusions to poems, rhymes, fairy tales and stories.

It also intersects with the past through its gothic roots which establish it as belonging to a genre wrapped up in curses, ghosts, and death. As the film opens, backpackers and friends Jack and David have begun their tour of Europe -notably the birthplace of many landmark gothic novels- arriving in the village of East Proctor. Its picturesque, pastoral setting conjures up the lyricism of poets such as Byron, Keats and Wordsworth who formed part of the romantic movement that took place in Europe towards the end of the 18th century.

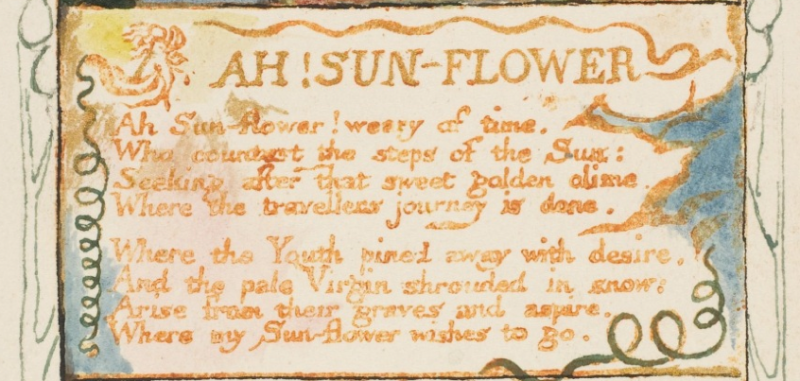

Yet the space simultaneously possesses a quiet, menacing quality, one which can also be found in the works of another romantic poet William Blake, in his collection entitled Songs of Innocence and Experience. This body of work, split into two parts, takes first a naïve and ideal view of the world (songs of innocence), followed by a more cynical one (songs of experience) which in turn, reflects the two phases David moves through prior to and after Jack’s death. Blake’s work also contains a great deal of pastoral and animalistic imagery, including one poem headed The Lamb providing links to the film through the sheep truck we see the friends first arrive in and the name of the secretive and foreboding Slaughtered Lamb pub.

Before David battles his transformation from man into monster, he and Jack are seen strolling through the moors. Although they have been issued with multiple warnings from the villagers to keep to the path and stay away from the danger of the moors, they soon find themselves lost and directionless. Not knowing the way forward and having no means of retracing their steps, their predicament parallels that of Hansel and Gretel in one of the Brothers Grimm most disturbing tales, acting as a signifier that events are about to take an unwelcome turn. Vast and sprawling, this land contains valleys, dales and trees-immediately recalling the wooded settings of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale or the rustic countryside of a Bronte novel. With a history that dates to the Mesolithic era, through to Anglo-Saxon and Viking occupation, the earth on which Jack and David tread is steeped in the lives of communities of yesteryear and a heritage that circulates them as closely and as unseen as the beast.

The relationship between the moors and the stories, fables, and tales of old are not just recognisable to the viewer, but Jack and David themselves refer to Emily Bronte’s 1847 Wuthering Heights and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1902 The Hound of the Baskervilles, two literary works that share thematic connections with the film. Emily Bronte’s gothic masterpiece Wuthering Heights aligns specifically with the environment of the first part of American Werewolf in being set within the Yorkshire Moors. However, unlike the detective genre penned by Conan Doyle, Bronte’s work also mirrors the romance between Alex and David with Cathy and Heathcliff. Both the novel and the film also contain scenes involving nightmares and explore the supernatural through depictions of ghosts who haunt the living.

LISTEN TO OUR HORROR PODCAST!

Despite being set in Dartmoor, Devon, Conan Doyle’s most popular entry in the adventures of Sherlock Holmes series has much in common with the film as it centres around a deadly curse and a demonic hound-a blueprint for American Werewolf if ever there was one. Elsewhere, The Hound of the Baskervilles and the film also share the twin settings of both rural countryside and metropolitan London as well as an undercurrent of mystery and suspense. Although not mentioned specifically in the film, aspects of its story also echo the 1740 fairy tale by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, La Belle at La Bete (Beauty and the Beast) in its depiction of a young woman who falls in love with a person who is half-man, half-monstrous creature.

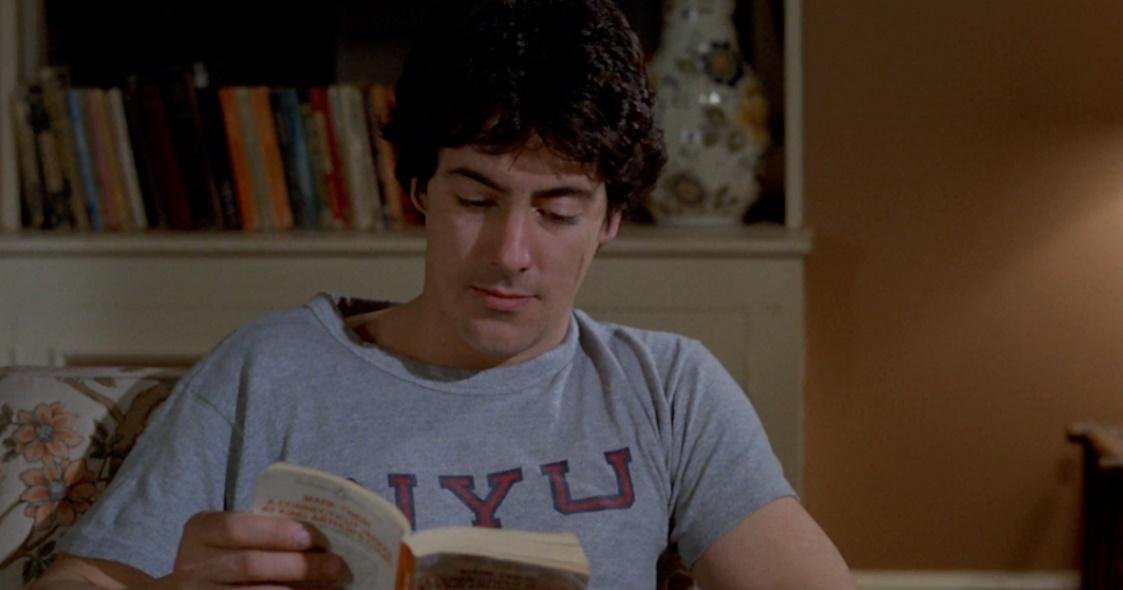

While David recovers from his attack on the moors in a London-based hospital, he is tended to and cared for by Nurse Alex (with whom he will become romantically involved). One night, she reads him a story entitled A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court, a novel written by Mark Twain in 1889. With its setting of castles and courts, this evokes the history of the medieval period whilst the title and mention of ‘the stranger’ character also reflects David’s own othered status-as a werewolf and as an American Jewish man in London. On the walls of David’s room in the hospital there is a painting of Van Goughs Sunflower’s. There are multiple ways of reading this image-is it a means of echoing the romanticism and connection to nature through a possible link to another William Blake poem Ah! Sun-Flower, or (with Van Gough having been believed to take his own life aged just thirty seven) is it a rumination on the theme of suicide which pervades the film?

While the film successfully provides an update of the classic Universal Classic Monster films such as Werewolf of London and The Wolf Man (which in turn draw heavily from the deep well of the gothic genre), An American Werewolf does not abandon its influences and attachments with the gothic or to put it more aptly, with its own past. There is in fact, evidence to be found throughout the film that ties it very closely to the genre as it contains many of its key ingredients. After being attacked by the werewolf, Jack returns to haunt his surviving friend David, visiting him as an angel of death in the hospital, at Alex’s apartment and in the cinema. This notion of the past haunting the present-or the dead tormenting the living is a reoccurring one that runs through gothic literature.

The importance of architecture and space is also fundamental in gothic tales and although this is usually depicted in the form of ancient ruins or prestigious buildings, American Werewolf puts a contemporary twist on an old tradition. It does so by utilizing the less typically gothic but equally effective sites and spaces of London with the winding confines of the underground tube acting as a replication of the labyrinthian corridors of medieval castles while the London taxicab becomes the modern version of the ominous horse and carriage which often signifies-or carries someone-to their doom.

The gothic also places close focus on the battle between forces of well-intentioned humanity and supernatural powers from beyond, a conflict which we see in contest within David through his choice between fighting or surrendering to what is ultimately inescapable. This sense of inevitability and entrapment often felt by the protagonist is built upon through the impact the landscape has upon their psyche and which will come to play a key role in their later fate. In both East Proctor and London, David is an outsider in unfamiliar surroundings, surrounded by unfamiliar people which adds to his anxiety and state of mind.

A change in location also features prominently in gothic storytelling along with the device of a tale within a tale. Both are used in American Werewolf, first in the shift from East Proctor to London and secondly we see the story within a story technique used through David’s dreams within dreams and a change in narrative in the inclusion of clips from the Muppets and the tabloid television advert that David watches in Alex’s apartment. Finally, the proliferation of dreams and dream sequences and a focus on the nocturnal which is repeated throughout the film also serves to connect it to gothic sensibilities.

LISTEN TO OUR HORROR PODCAST!

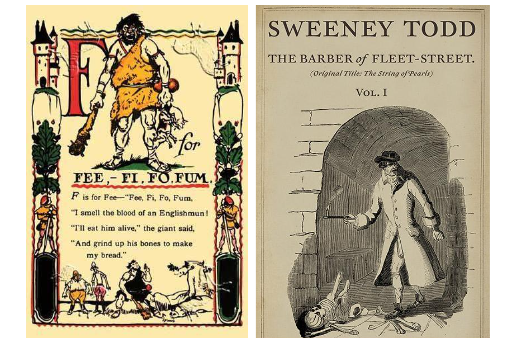

In the well-known English fairy tale Jack and the Beanstalk, a young boy exchanges his family cow for some magic beans which eventually grow into a beanstalk, taking him to a castle in the clouds inhabited by a malevolent giant. In the build up to the werewolf transformation scene of the film, David paces up and down the apartment and, looking in the mirror he recites a rhyme spoken by the giant: ‘Fee-fi-fo-fum! I smell the blood of an Englishman!’ This intertextuality between the film and the fairy tale is both knowing and multitudinous in that not only does David have a (now deceased) friend named Jack but, he is (like the giant in the story), bordering between the monstrous and the human in his appetite for blood. While the Jack in the Beanstalk tale eventually conquers the giant and survives, David must put an end to his own carnivorous compulsions.

With David having completed his first cycle as a werewolf, the film careers towards its final and devasting act. Unbeknown to David, Alex plans to commit him into the care of her superior at the hospital, Dr Hirsch. As she pulls an excitable David into a hackney taxi which she directs towards St Martins’ Hospital, the demi-beast sat next to her remains oblivious about the nocturnal activities he has been engaging in. This spell of innocence, however, is suddenly and abruptly broken by reference to yet another tale that makes up the intertextual tapestry of the film when a London cabbie remarks upon how the previous night’s murders put him in mind of the Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

A folktale that has its origins in the Penny Dreadfuls of the 1800s, the now familiar and much adapted story of Sweeney Todd, a murderous barber who baked his victims in pies, is macabre and barbaric and in being set in London has specific geographical ties to David’s current location. The violent imagery and associations of murder and bloodshed trigger David’s memory as the past interweaves with the present once more, resulting in traumatic realizations and horrifying consequences.

In American Werewolf in London, Jack and David find themselves in a time and place where the past is ready to attack and murder one of them and torment the other to eventual death. This convergence of history with the present is told first and foremost through cinematic technique but it is also explored in a more covertly and intriguing way through the abundance of references, symbolisms and signposts to stories, fables, and folklore. From the connections we make between the landscape of East Proctor to works of great literature, to the psychological torment and murderous rampage of David that are reflected in the retelling of local legends, the film not only tells its own story but it tells the tale of how the past and the present are engaged in a constant and ever-fascinating interaction with one another.

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Bucket List of the Dead, Blood Drive, Candy Land & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696261000263-58VQFOVWPE363OFGP7RF/GHOULS+WATCH.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Tender Is The Flesh with Zoë Rose Smith, Bel Morrigan and Liz Bishop](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693769261264-MS4TS4Z4QC1N15IXB4FU/Copy+of+%5BJuly%5D+Antiviral%2C+possesoor+and+infinity+pool.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Antiviral, Possessor & Infinity Pool with Zoë Rose Smith, Amber T and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691238787263-XYRKXW2Z7RWI9AY2V2GX/%5BJuly%5D+Antiviral%2C+possesoor+and+infinity+pool+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Body Horror Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691238687847-L9U434I1U4HZ3QMUI3ZP/%5BJuly%5D+Ghouls+Watch+-+Website+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Bones and All, Suitable Flesh, The Human Centipede & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687855203348-7R2KUSNR6TORG2DKR0JF/%5BJune%5D+Ghouls+Watch+-+Website.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] 3 Original vs. Remake Horror Films with Rebecca McCallum & Kim Morrison](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685286663069-0Q5RTYJRNWJ3XKS8HXLR/%5BJune%5D+Original+vs.+Remake+Horror+Films.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: The Devil’s Candy, Morgana, Dead Ringers & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685284429090-5XOOBIOI8S4K6LP5U4EM/%5BMay%5D+Ghouls+Watch+-+Website.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Ruins (2008) with Ash Millman & Zoë Rose Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684076097566-BE25ZBBECZ7Q2P7R4JT4/The+Ruins.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Deathproof, Child’s Play, Ghostwatch & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682447065521-DWF4ZNYTSU4NUVL85ZR0/ghouls+watch.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] 5 Coming-of-Age Horror Film Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1681418402835-EMZ93U7CR3BE2AQ1DVH4/S2+EP5.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Good For Her Horror Film Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678634497037-W441LL37NW0092IYI57D/Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Ghouls Watch: Severance, Run Sweetheart Run, Splice & more](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677589685406-YZ9GERUDIE9VZ96FOF10/Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Loved Ones (2009) with Liz Bishop](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1676369735666-56HEK7SVX9L2OTMT3H3E/GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Terrifier (2016) & Terrifier 2 (2022) with Janine Pipe](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1674478017541-0DHH2T9H3MVCAMRBW1O1/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+4+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Krampus (2015) with Megan Kenny & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839790368-VYX6LIWC5NVVO8B4CINW/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+17.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Soho Horror Film Review with Hannah Ogilvie & Caitlyn Downs](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840392291-XQGQ94ZN9PTC4PK9DTN1/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+16.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Borderlands (2013) with Jen Handorf](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839985316-KPLOVA9NGQDAS8Z6EIM9/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+15.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Soho Horror Film Preview with Hannah Ogilvie & Caitlyn Downs](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840411619-IP54V5099H6QU9FG4HJP/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+14.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Halloween Special: 5 Horror Films to Watch This Halloween with Joshua Tonks and Liz Bishop](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840351086-2AWFIS211HR6GUY0IB7I/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+13.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Horror Literature with Nina Book Slayer & Alex Bookubus](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840273346-ASHBRDHOKRHMGRM9B5TF/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+12.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Alien with Tim Coleman and Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839878802-LR40C39YGO3Q69UCCM62/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+11.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination with Jenn Adams and Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839916928-KK9CTT0OAKACXLGYA9DX/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+10.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Dark Water with Melissa Cox and Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839939630-BLPIHIDVRJE9FC1A9BRZ/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+9.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Noroi: The Curse & Perfect Blue with Sarah Miles and Ygraine Hackett-Cantabrana](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682950816911-7ZCMPP8H0BSUPCPZYQ07/_PODCAST%2BNO%2BIMAGE%2B2023%2BEP%2B8.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Wicker Man with Lakkaya Palmer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672839898764-VIYDC7ZD8QTBCGK562NL/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+7.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] You Are Not My Mother with Ygraine Hackett-Cantabrana](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840165939-VP0CIKOM4KPX67JLNHDB/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+6.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Trouble Every Day with Amber T](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672837846372-19MMMAF5WCOORZXNRIY3/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+2.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Invitation with Hannah Ogilvie](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672838145193-OW65KNC5POZN5FE5KZHK/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+3.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Let The Right One in with Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840623893-Y1MMPNYPDEPGI9J5BJC8/_PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+4+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Interview with a Vampire & Bram Stoker’s Dracula with Dr. Harriet Fletcher](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672840081289-714FCGZ8MYU4BUG9RRWC/Copy+of++PODCAST+NO+IMAGE+2023+EP+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)