[Editorial] J-Horror: Ring (1998) versus The Ring (2002)

Two teenage girls sit in a bedroom, discussing a strange urban legend. It’s about a video tape containing strange images all centred around a mysterious woman, and the death that befalls those who watch it one week later. One of the girls is uneasy, recently having watched a strange tape while on a trip with some friends. Suddenly, the phone rings. The girls run downstairs to answer the phone, the uneasy girl’s friend answers and passes it to her with a horrified look on her face, and then…

What?

Does she say “moshi moshi” or “hello”? Are these girls Tomoko and Masami or Katie and Becca? Is the videotape that of Sadako Yamamura or Samara Morgan?

Are you watching Hideo Nakata’s Ring or Gore Verbinski’s The Ring?

Remakes can be a very touchy subject, particularly amongst horror fans. When it comes to the Asian horror remake boom of the early 2000s, The Ring is considered the beginning and the best, and not without reason, as whilst the ones that followed have their fans, none of them ever reached the level of mainstream public consciousness that The Ring did. For me it was something of a game changer, because even though I had watched horror movies before, The Ring would consume me and introduce me to a world of new terrors that made me who I am today. So whilst The Ring wouldn’t exist without Ring, I would possibly never have watched the former if it wasn’t for the latter, and I imagine it is similar for a lot of other horror fans of my generation. This means that the question of which is a better movie is a difficult one to approach, but much like both films’ intrepid reporter protagonists we will endeavour to investigate what sets each film apart, what they share, and ultimately which is more worthy of a place on your shelf.

You probably do not need the story of Ring and The Ring explaining to you at this point. Both films take their plot from the novel Ring, written by Koji Suzuki and published in 1991. Whilst the novel will be initially familiar to fans of either movie, there are some big differences. For one thing, the novel is not really a ghost story but rather more of a sci-fi mystery thriller based around psychic powers. There is also a male main character instead of a female one, Kazuyuki Asakawa rather than the Reiko Asakawa of Ring or Rachel Keller of The Ring, and it gives the impression that his involvement in the case of the dead teenagers is initially reluctant despite his niece being one of the victims. Ryuji is also a drastically different character, being a jaded nihilist who ponders about whether e humanity deserves destruction whilst also being either a serial rapist or lying and claiming to be one for his own amusement. As for Sadako herself, as said the book isn’t a ghost story so we don’t get anything like her famous appearance, and the “curse” is more of a psychically transmitted virus based on smallpox. She is also intersex, possessing both male and female genitalia, which was possibly a choice made to emphasise her as otherworldly and outside the “normal” scope of humanity. It’s a good book, and has an atmosphere of its own that keeps you on edge, but streamlining the story for the screen was necessary.

Interestingly, Hideo Nakata’s film was actually not the first adaptation of Suzuki’s novel. Ring: Kanzenban was a 1995 made for tv version that whilst closer to the events of the novel, is very rough looking and has a lot of particular quirks, not least of which is Sadako being constantly topless. Really, if we’re splitting hairs, The Ring isn’t even the first remake of the Japanese film as whilst the 1999 Korean film The Ring Virus positions itself as a readaptation of the novel and has certain novel specific story elements sharing some of the exact shots and moments with Nakata’s film, including ones not appearing in the novel.

Ghost stories in Japan traditionally veer towards historical settings. One of the inspirations for Sadako on film was the story of Okiku, a ghost who haunts a well on the ground of Himeji Castle. Versions of the legend vary, but what is consistent is Okiku being thrown in the well after being falsely accused of stealing one of ten precious plates, and her ghost arising from the well sobbing, counting to nine before giving a terrible scream in place of the lost tenth plate. Another is the story of Oiwa in Yotsuya Kaidan, considered by some to be the most famous Japanese ghost story. It is a story of a woman betrayed by her husband, poisoned, disfigured, and disposed of so that he may marry a younger, richer, woman, before she eventually comes back from the grave to enact her revenge. Oiwa’s story has been told many times in Japanese media, and it is traditional for the production team to visit the reported grave of Oiwa in Myogyo Temple, Tokyo, to ask for her blessing, as not doing so may bring misfortune upon them. One particular physical characteristic of Oiwa’s is a bulging malformed eye, a result of the poison, not unlike the one that Sadako’s victims see before death. In many ways Oiwa is the grandmother of what we know on screen as the typical ghost of Japanese horror, she is an onryō or “wrathful spirit” killed in tragic circumstances and capable of causing harm to the living for the sake of the wrongs committed against her in life. By making Ring a ghost story and bringing those traditions of the ghost story to the modern (for the time) day, it creates a clashing of old and new, traditional and contemporary, spiritual and technological.

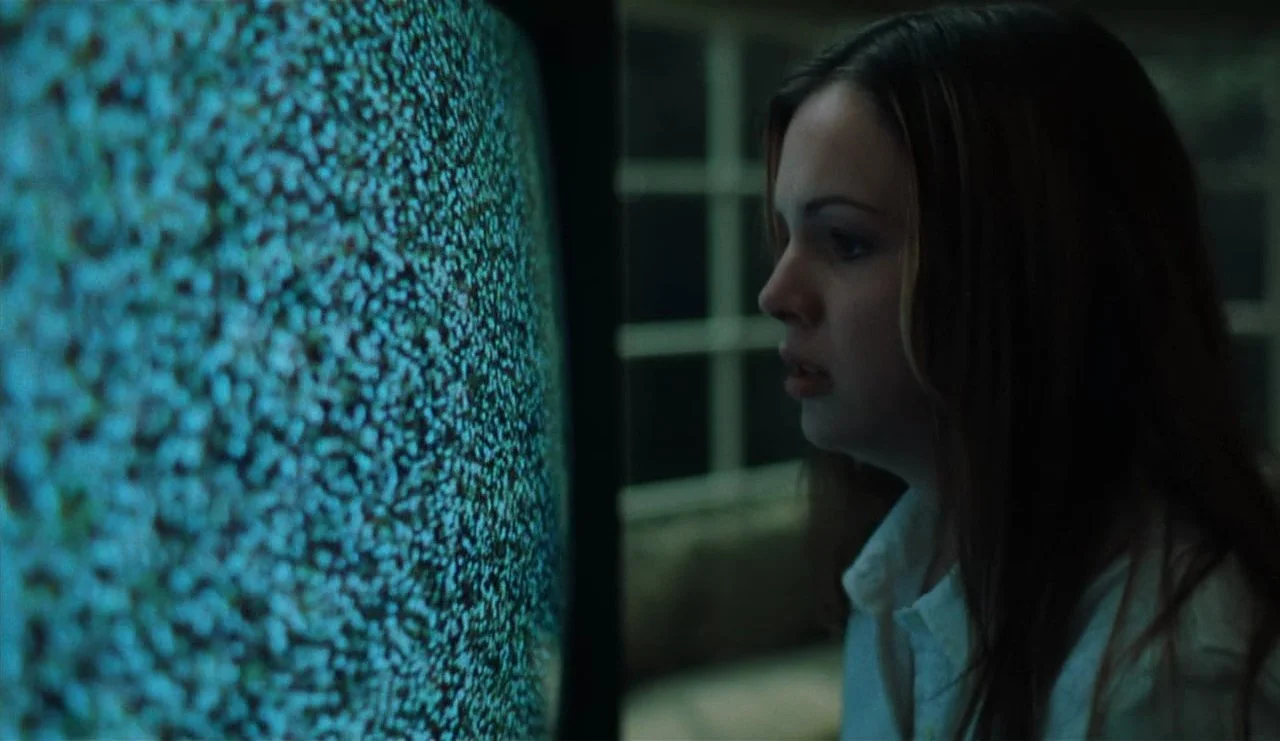

Where Ring is a modern application of the classic ghost stories of Japan and supernatural fury affecting the living, The Ring is modern American Gothic. Isolated landscapes, even when in the city, mixed with foreboding overhead shots which emphasise how small and alone the characters are against these events. The places that we see over the course of the film; the mountain retreat, the island community with the lighthouse, the horse farm, feel like corrupted versions of a pastoral ideal. It’s as if nature itself is tainted. It would be unfair to say that The Ring is a louder, less nuanced version of Ring with CGI slapped on top. There are moments that are certainly less effective in the remake; the climactic scene involving a television set doesn’t quite land in the same way. However overall, the original film’s mood and ingredients have been translated, altered as needed to better fit its new setting. It’s a better approach than later j-horror remakes would take, transplanting the plot whole cloth without thinking of how to make it fit in a Western setting more effectively. Apart from Samara herself, the psychic element is non-existent in The Ring. Our Ryuji analogue Noah is just a normal guy and any visions experienced by Rachel are played as a by-product of Samara’s curse.

The scares are a lot more visceral in The Ring. Yes, there are jump scares, but they avoid the pitfall of being pointless by actually showing something scary when they happen rather than being a fake-out designed to prod the audience into a reaction. The twisted, water-logged corpses of Samara’s victims, done beautifully with practical effects courtesy of industry legend Rick Baker, are pure nightmare fuel and the fleeting staccato glimpses we get of them serve to make them stick in your mind even more. Also memorable is the infamous ferry scene where a horse leaps to its death under the presence of Samara’s curse in Rachel. Ring is more low-key and grounded in the familiar, but the effect of the horror on that is letting you soak in dread with each passing day that the characters get closer to their deadlines. There is little score, relying instead on high pitched drones and groans but that burst into a chaos of strings to give extra impact in a few instances, such as when Reiko’s son Yoichi watches the cursed tape.

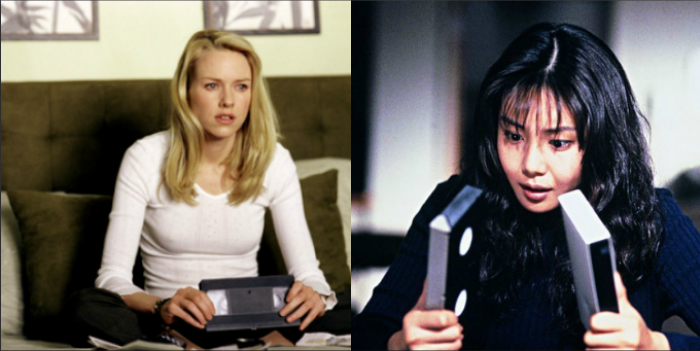

Rachel is also a much more compelling character than Reiko, aided by an intense but occasionally vulnerable performance by Naomi Watts and feeling a lot more assertive and active. That’s not to say that Reiko is a bad character, she’s just more swept along by the horror as a result of her curiosity in investigating the urban legend, even before knowing about its connection to her niece’s death. The mother-son dynamic is quite different between the films, which is also something affected by cultural background. Reiko as a career focused and divorced woman is something that would be at odds with more traditional views of gender roles in Japan with women as housewives and caregivers. Indeed, her tendency to leave her young son home alone until late in the evening is something that makes her ex-husband Ryuji, who isn’t even involved in Yoichi’s life in any significant way, very uncomfortable and he encourages her to spend more time with him as her deadline gets closer. But Reiko clearly does care about her son, as it’s his survival that concerns her more than her own. Similarly, there is a distance between Rachel and her son Aidan, exemplified by him calling her by her first name, and her experiences trying to stop Samara’s curse push her to pay more attention to him and his needs. The creepy child in a horror movie is hardly a new thing, and whilst Yoichi at least acts like a normal child on occasion, Aidan is far too cliched with his whispering ominous lines and sinister drawings.

There are certain themes and elements that the films share, albeit with different approaches. One is water, and it goes deeper than just the wells that house Sadako and Samara. In Japanese folklore, water holds significance as a barrier between the physical and spiritual worlds. It’s also tied directly into Sadako’s origin, as it’s hinted that her biological father was some kind of eldritch sea deity. Samara, on the other hand, has a deliberately vague origin which would only get more muddled in sequels. In The Ring everything has this damp feeling; it's almost always raining, water flows out of the television to signal Samara’s arrival, and the blue-green filter that was a weird trend in early 2000s horror fits perfectly here as it gives everything a decayed, sick, water-logged feeling. You feel uncomfortably cold watching the movie.

So which is the better film?

Honestly, neither.

It sounds like such a cop-out answer, but it’s true. With later remakes of Asian horror films it’s a lot easier to pick a side because of things like lazy effort (One Missed Call), a lack of understanding what made the original so significant (Pulse) or a combination of both (Shutter, just….Shutter). However, with Ring and The Ring it’s not that easy. They’re both great films, they’re just slightly different flavours and which one you watch is personal preference. Personally, I go for Ring when I want that drip-feed atmosphere of dread and the iconic visuals, and The Ring when I want that film’s particular scares, performances, and setting. But whilst each film has its own quirks and flaws, whichever one you choose you’re going to have a great spooky time.

So how about we put all our differences aside and watch a nice videotape?

HAVE YOU LISTENED TO OUR PODCAST YET?

Sex abounds in these films, with varying degrees of acceptance. In The Wicker Man, Sergeant Howie is at once disgusted and fascinated by the rampant sexuality that pervades Summerisle culture. Alongside the lusty carnal delights of those involved in the ritualistic practices in these films, the concept of female sexuality is set apart, as something especially wicked and dangerous. In Blood on Satan’s Claw, Angel is positioned as a temptress, sent to lure the children of the village to their spiritual doom. Willow McGregor in The Wicker Man is a source of temptation to Howie, a constant winking and bum slapping reminder of his own baser instincts. The scene in which she tries to lure him, siren-like, through the walls of the Green Man Inn has become iconic, not only for it’s absolutely deranged nature, but also because it speaks to the intrinsic fears within these films, the women are wicked and must be burned. In Witchfinder General, this is made explicitly clear in the gruesome torture sequences, and we see this in Angel’s comeuppance in Blood on Satan’s Claw. What makes The Wicker Man so distinct in this trilogy, is its refusal to demonise female sexuality, instead we see Howie’s prudishness become his punishment, his refusal to partake of the sins of the flesh is intrinsic to his downfall.

Death and sacrifice are perhaps to be expected, given that these are horror films. But the approach within each film is notable in its distinctions. In Witchfinder General, death is something to be feared, a punishment for daring to cross a neighbour, or discredit a murderer sent on orders from the King. In Blood on Satan’s Claw, death stalks the fields, watching the children of the village through Angel’s eyes. It is a terror that awaits at the end of a children’s game of chase and is all the more disturbing because of it. In The Wicker Man, death is a celebration (although Sergeant Howie might beg to differ), and a natural part of the circle of life. The residents of Summerisle are at peace with their own mortality and are also willing to spill a little blood if their faith demands it.

A final shared theme is that of religious zealotry and bigotry. Matthew Hopkins is wielding his faith as a weapon, to collect money and the lives of those whom he believes deserves to die. He believes in his God given right to do so. In Blood on Satan’s Claw, tension arises between Reverend Fallowfield and Angel, as Fallowfield tries to impose order and faith onto Angel, who is wild in her newfound devotion to chaos-monster Behemoth. This conflict between Christianity, often positioned as the traditional faith, and the much older Pagan tradition is expertly teased out in The Wicker Man, in which Howie’s stiff, buttoned up faith is sardonically mocked by Lord Summerisle and clan. We are also treated to visually sumptuous ritualistic displays that evoke the direct contrast between the pagan worshippers and their Christian counterparts. In Blood on Satan’s Claw we see children roaming woodlands, bedecked in flower crowns and garlands (and some very strong eyebrows), in The Wicker Man the May Day parade is a spectacle of sinister papier-mâché animal masks and sword wielding dancers. Compared to the cold stone church, with its uncomfortable wooden benches and dreary sermons, is it any wonder the children in Blood on Satan’s Claw and the residents of Summerisle would rather frolic in the woods and fields? When faced with the rigid anti-pleasure, anti-woman rhetoric of Christianity, is it any surprise that people choose to occasionally bloody their hands in exchange for freedom?

As others have noted, folk horror is a feeling. It is not something readily pinned down for examination, rather you know it when you see it. As these three films highlight, there are many ways to bring forth the spirit of folk horror, but one thing is clear, if anyone asks you to come play in the woods, it's worth checking the date on the calendar first.

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Bay (2012) with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Amber T](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684751617262-6K18IE7AO805SFPV0MFZ/The+Bay+website+image.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682536446302-I2Y5IP19GUBXGWY0T85V/picnic+at+hanging+rock.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Psychotic Women in Horror with Zoë Rose Smith & Mary Wild](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678635495097-X9TXM86VQDWCQXCP9E2L/Copy+of+Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Nekromantik with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677422649033-Z4HHPKPLUPIDO38MQELK/feb+member+podcast.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 5 & Wrap-up with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841326335-WER2JXX7WP6PO8JM9WB2/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%284%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 3 & 4 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841151148-U152EBCTCOP4MP9VNE70/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%283%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 1 & 2 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841181605-5JOOW88EDHGQUXSRHVEF/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841247731-65K0JKNC45PJE9VZH5SB/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] A Serbian Film with Rebecca and Zoë](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841382382-RY0U5K7XD4SQSTXL2D14/PODCAST+BONUS+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)

![[Editorial] Ranking M. Night Shyamalan: his Good, his Bad, Not so Good, and his Twists](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687196229638-MMAFHN9EL2RXAEJO5G3B/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+18.21.53.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Aliens in Sci-Fi & Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685351258912-P3ETEO2CL7F54CS4QKX3/image12.png)

![[Editorial] The 9 Most Amazing Antler Deaths in Horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684065424643-3XDDCWVBM6CCQPXF4YTW/Image+2+%2840%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 of The Best Home Invasion Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1683913399685-G6Y54FFWUCL4CW6ISJB1/Image+1+%2841%29.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)