[Editorial] “I’m Your Boyfriend Now, Nancy!” A Sapphic Lens for A Nightmare on Elm Street

In the zeitgeist of the 80s slashers, it is a truth universally acknowledged that one of the queerest franchises is A Nightmare on Elm Street. I feel like I don’t have to fight y’all super hard on this. The second installment of the series, Freddy’s Revenge, has always been noted for its infamous queerness, both on and off camera. By the time we get to the third film, Dream Warriors, Freddy Krueger’s drag queen persona is solidified into the minds of every self-proclaimed horror aficionado with his legendary catch phrase “Welcome to prime time, bitch!”

But what about the one that started it all?

For a bisexual woman with an American-midwestern upbringing in the 90s, the classic video store home-away-from-home story was not my experience. Horror was something forbidden, sacred, and only accessible by limited permission or white-lie omission. And while Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund) is without a doubt the breakout star of A Nightmare on Elm Street, I was so deeply drawn to the final girl in the pink sweater vest. So when I evenutally emerged from my backwater chrysalis and into a feminist film theory class, you can imagine my surprise to find that one of the most pivotal young queered women I had seen on screen, Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp), was not being given her flowers. I was even more shocked when I got to that seminal next class, queer horror theory, and the film wasn’t even on the radar for discussion.

Maybe I’m crazy. Maybe I’m not. Art is subjective and in the spirit of fun and new perspective, let’s take a look at some of the relationships and tones of the original film and discuss another reason why Nancy Thompson is such an icon in the pantheon of Final Girls.

Steam hisses, knives are sharpened, and a horrible monster reveals himself against the flames of his own personal hell. Christina “Tina” Gray (Amanda Wyss), a frightened young blonde in a thin white nightgown, dashes her way down a foggy, dripping tunnel as an unknown voice whispers her name. The monster taunts the girl deeper into his labyrinth, laughing behind shadowy corners as she falls further into his trap. Suddenly, he slashes at her from behind a hanging sheet and chases the terrified innocent into a corner. Trapped between her living nightmare and a fiery furnace, she screams!

With the fantastical beauty of Wes Craven’s vision and his team’s execution, the opening dream sequence between Freddy and Tina paints a restrained but potent surrealist gothic tableau. Because there is a printed logic given to Freddy’s transference from teen-to-teen (Freddy Krueger enters your mind as the children of Elm Street pass along in his memory) we can forget that the pure manifestation of his evil is borne of something otherworldly — a supernatural serial killer. This basic principle allows A Nightmare on Elm Street to let Freddy evolve from film to film, through its allusion of the fantastical.

The notion permeates throughout the story, with other examples being seen in the pinafore’d jump-ropers and their haunting melody of “one, two, Freddy’s coming for you,” or the multiple funeral scenes set in graveyards (something that the original film is touted for in the history of the genre). Religious imagery is a constant, with a crucifix playing a part in scenes surrounding Nancy and Tina. And almost all of the pre-stated imagery is established before we even meet our heroine. Gothic surrealism, and the seductive undertones that traditionally accompany it, seeps into the American 1980s cul-de-sac and into the young minds of our puberty-riddled youth when they are at their most vulnerable — in their dreams.

But as quickly as you can close a chapter of a book, Tina is awake and confronted by her mother. Hearing the screams and seeing her daughters scratched up nightgown who simply states a line that has haunted my mind since I was a teenager:

“You gotta cut your fingernails or you gotta stop that kind of dreaming.”

Tina’s first contact with intimacy in this film does not come in the arms of a boyfriend, but rather with her best friend Nancy as they are driven to school together by Nancy’s boyfriend Glen Lantz. I can legally say this because he does not have a line until one full minute after his visual introduction. Glen is set dressing to the conversation being held even after the arrival of Rod Lane (Nick Corri), Tina’s on-again off-again beau, who she also immediately dismisses. The relationships with the boys of the film are established as second place to the relationship between the two girls.

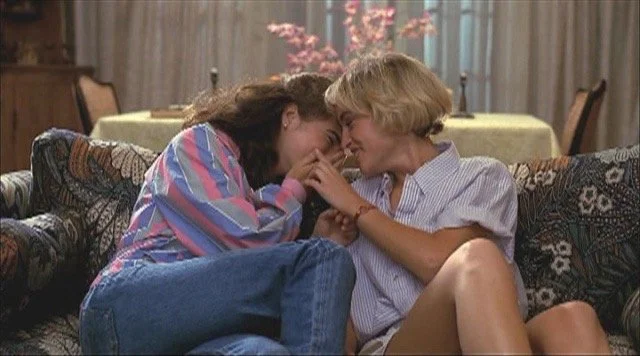

This casually leads to an immediate smash cut to a sleepover. Nancy does Tina’s nails as they giggle together, ribbing at Glen who for some reason is also there. They press their faces together as they fall back laughing at his terrible attempt to establish a believable alibi with his mother. This playfulness comes from a very comfortable, physical relationship shared between the two girls. When Tina looks into Nancy’s eyes, they begin a mesmerizing in-depth discussion of what they have seen in their dreams. It’s scary, but eerily similar. Nancy and Tina have a moment of shared vulnerability that Glen literally has to shove a bowl of popcorn into so that he can get his girlfriend’s attention back. It is when Tina hears a noise that she immediately jumps to Glen’s arm for protection. Nancy manages to sneak her own arm in between them though, grasping at her boyfriend’s waist as if reminding herself what is expected.

This is the point in time where history would traditionally slap this author with a time-old classic. After all, perhaps they’re just very good friends.

But with the established queer landscape of physical and emotional intimacy, suddenly thrusting the boyfriends into the their traditional roles feels strange. And when Rod emerges, Tina falls back into a heteronormative paradigm. And yet she still seems to reject it, even as she is being dragged off to the bedroom.

“You guys are gonna hang around, right? Don’t leave me alone with this lunatic.”

Nancy continues the trend by keeping her rather passive boyfriend in line.

“Glen, not now. We’re here for Tina now, not ourselves.”

That night Nancy sleeps alone in Tina’s bed, an act that while not overtly strange, does conjure some imaginings of its own. This is not lost on Freddy Krueger. Even in sleep, the girls’ relationship is constantly referenced. The famous wall palpitation scene where Krueger menacingly hovers above Nancy takes place during a moment between toying with Tina in her nightmare. When he finally does attack, Tina actually calls out to Nancy first before calling out for Rod.

But like so much Lucy and Mina, their time together is cut short by a monster. Tina, who until now has been set up to be the assumed lead of the film, passes the torch of agency from herself to Nancy. Despite her death, Tina remains a telltale heartbeat of the story, and it is not the last we see of her.

The first time that we as an audience experience Nancy and Freddy together in the dream world is when she falls asleep in English class. Immediately she is met with the haunting image of a mangled Tina, whispering her name and reaching out from behind the semi-translucent plastic of her body bag — a ghost, beckoning for Nancy to follow. And like Heathcliff shouting Cathy’s name across the moors, she gives chase right into his arms. Or rather, the arms of Krueger disguised as a female hall monitor. Rather than start with the classics like self mutilation, scraping his glove along surfaces, or just straight up popping out of nowhere and looking like a demonic burn victim, Freddy first appears to us in Nancy’s nightmare as teenage girls — one to entice, the other as an avatar along her descent into his domain. Even in his true form, Freddy himself does not elicit fear from Nancy as he does with Tina, so instead he begins a different type of psychological assault; revulsion. As she burns herself to wake up, Freddy rapidly flicks his tongue at her mimicking an act of oral sex.

Krueger’s hyper-exaggerated sense of the dramatic is often equated to his other works in his filmography, and his use of it in the original A Nightmare on Elm Street is comparatively small. As a result, when utilized it is both deliberate and effective. Drawing Nancy in with images of Tina, Freddy often frightens her with sexually charged accompanying acts. This is arguably the start of his ongoing use of sexual deviancy as a weapon for eliciting fear in queer coded characters. (In Freddy’s Revenge, he attempts to seductively push one of his knife-fingers into Jesse’s mouth. In Dream Warriors, he holds Taryn against an ally wall with his crotch as he nails her to the building with syringe-fingers of drugs.) So as Nancy drifts off to the haunting tune of Freddy’s lullaby and his hand emerges between her legs in one of the most iconic scenes of not only A Nightmare on Elm Street, but possibly the whole franchise, it is curious that it is a non penetrative action. As his touch ghosts along her naked body, the threat to Nancy once again appears to be related to what he’s doing with his tongue, rather than with his hands.

Nancy’s disinterest in heteronormativity continues as she begins to seriously undergo her Final Girl journey towards understanding and defeating Krueger. When Glen shows up on the trellis outside his girlfriend’s window, she immediately makes it clear he is not welcome. He eventually bickers his way into her bedroom, which yet again begs the question why these two are even a couple. When Nancy tries to engage in the same acts of intimacy she shared with Tina in describing her dreams, she is immediately shut down by Glen, who is clearly not being honest with himself about his own encounters. Instead, she assigns him a simple task where a quick joke is made alluding to sex. Nancy once again firmly shuts down any notion of the sort.

When Nancy surprises Freddy in the dreamscape he once again conjures Tina as a distraction, this time as a grotesque mockery of something worshipful. Her plastic body bag mimics a nun’s habit as she weeps blood. Phallic creatures infest and invade her body repulsively - the image of something she once loved now perverted. Freddy taunts her with Tina’s face, teasing Nancy to save her before ripping it off and revealing his own. Glen’s continual impotence in her life is put on display as Freddy pins Nancy to the bed next to her boyfriend’s sleeping body.

In the final act, an attempt is made to make Glen’s ultimate demise seem tragic. He and Nancy meet on a bridge where he eats fast food and talks about how to take away an evil entity’s power in a dream via something he calls “dream skills.” She takes the idea and exits without a single physical interaction with him whatsoever. In fact, it is about 59 minutes into the film before we have a scene where Nancy is actually happy that Glen is in her life. Specifically, when he is not even present. Much like a love letter between Mina and Johnathan he feels “a million miles away” across the street as Nancy sits at her barred bedroom window. She asks him to wake her up so that she can bring Freddy into the real world and end this nightmare. He drops the L-word. She does not say it back.

In this hazy state of unease, Freddy is once again able to slip into Nancy’s seven-day-awake brain proclaiming that: I am your boyfriend now’, once again taunting her before shoving his unwanted, flapping tongue in her mouth via the disconnected phone.

Re-entering the dream world for their final showdown, Nancy is prepared for what she finds. First, the crucifix that Tina clung to keeping the nightmares at bay — the same one that fell onto Nancy as Freddy palpated his pay into her mind. Only after does she find Glen’s bloody headphones. Both of these items do nothing to fuel her fear, but rather toughen Nancy up for the fight ahead. When she is able to pull him into the real world, Freddy’s impotence is finally within Nancy’s control. He rants and rails between booby traps, but ultimately they are the empty threats of a man who no longer has the power to control her with fear.

Now, do I think that during any point of his life that Wes Craven knew what lesbian manicure was? Probably not. But at its heart, horror is queer. Monstrous puberties and monstrous coming out stories have a long standing tradition of going hand-in-hand (Carrie, Freddy’s Revenge, Jennifer’s Body) and because so much was not overtly made for us for so long, we often find versions of ourselves in the cracks. But what’s kind of cool is that A Nightmare on Elm Street is not a traditional coming out story but rather it is about coming to terms with who you are, your own fears, and conquering them. Nancy’s fear throughout the film is controlled by her affection towards Tina and the rejections she encounters when attempting to share that type of intimacy with others. It is only when she comes to accept that this is part of herself is she able to take away his power.

Because as the final scene of the film dictates, it isn’t enough to kill him physically.

As Nancy, Tina, Glen, and Rod drive off into the distance under a harrowing red and green striped convertible top we are simply reminded:

Be honest with yourself. You have to overcome your fear. Or else, you may be forced to live in it forever.

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.