[For The Love Of Franchises] The Genesis Paradox in the Alien Franchise

For sake of space, this article refers to and examines characters and scenes from the Alien franchise for an audience familiar with the movies themselves.

The Alien (1979-present) franchise has been a cornerstone in science-fiction horror cinema. There is clear scholarship and recognition that this franchise relies on the female bodily experiences, often positioned in parallel to the xenomorph’s own body, to convey monstrosity and anxiety around body invasion (Bueno, 2010). However, there remains to be a holistic evaluation on how the power dynamics among key characters in the franchise, the bodily comparison between aliens and humans, and creation themes all echo the archetypal narratives rooted in Genesis.

Though such connections to Genesis might promote and further patriarchal dynamics place upon women, the Alien franchise challenges this by allowing the female body and perspective to be at the forefront to in turn promote agency, survival, and transcend from a binary restraint that ultimately shows only a woman can be a worthy threat to the xenomorph’s existence. This article will first outline the Genesis paradox that will be apparent explicitly in Alien (1979) and then how the paradox is extended, solidified, and readapted throughout the Alien franchise (1986, 1992, 1997; Prometheus 2012, Covenant 2017).

Genesis Paradox

It isn’t unknown that, especially upon the release of the prequels, esoteric aspects of the Alien franchise have been speculated upon amongst fan groups and platforms. Themes of creation, seeking the origin of humankind, and pregnancy have heavily influenced the Alien narrative and world building. This is why it is important to see how the archetypes in Genesis were foundationally built in the first film but then expanded throughout the series.

The Book of Genesis is one of the most well-known, if not the creation archetypal narrative in Western society. The first four characters and archetypes introduced are God, the creator of the universe, Adam, the embodiment of man, Eve, the embodiment of woman, and the serpent, the embodiment of nature. The concept I rely on is called the Genesis Paradox because one might think that utilizing and revisiting the gendered power dynamics rooted in Genesis favors the patriarchal motivations of the story, however, relying on such narratives, as shown in the Alien franchise, puts forth the strength, agency, and complex relationships that are imposed onto the matriarch.

Eve is seen as the fall of man, a temptress who consorts with an unknown serpent creature-like entity in retaliation with God and, man, Adam. Furthermore, it is her womb that brings forth a lineage of men who shed blood and have to redeem themselves in enlightenment, to God, as they are born of sin. Not only is Genesis a story of creation, but such disturbed creation is the consequence based on the actions of a woman. In the Alien franchise, we see that even though women are consistently at the centerfold of Alien’s own creation story they persistently are the ones that act against and try to prevent the fall of ‘man,’ reinstate their maternal/caregiver aspects, have great concern for humanity’s well-being and utilize their seemingly innate relationship with ‘other entities’ to their benefit rather than their demise.

Alien (1979)

It is not obvious that Ripley would be the survivor of the xenomorph invasion imposed on the cargo ship, the ship’s computer called mother. In Genesis, Eve is shown to bring destruction to the garden of Eden, the idyllic land of creation and potential, by engaging with an unknown entity, the serpent. However, it is Ripley, the dominant female character and sole human survivor, that consistently refuses to engage and bring forth onto the ship an unknown entity that does hold within its existence the demise of man. As the crew approaches the ship with an injured, unknowingly impregnated, crewman named Kane, Ripley consistently refuses them entry – trying to stop a literal and metaphorical invasion of the body, the ship’s body, and their own. Such power dynamics are arguably not a coincidence; though Eve is shown to fall victim to the inclusion of an unknown creature, Ripley, a woman and keeper of the ship, repels such naiveness with expertise trying to follow precautions that could dispel such an invasion. By evoking these Genesis dynamics, we see that it is the men themselves who are now victims of the invasion and disruptive desire that the unknown serpent-like entity grants them.

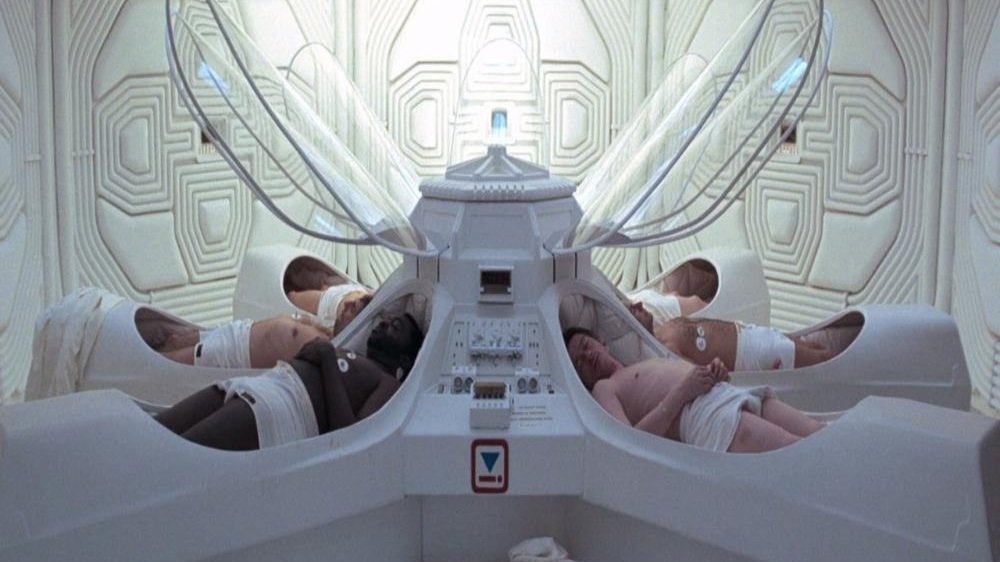

Cementing men as the initial site of birthing horror, rather than women stems from Alien (1979). It is Kane that is the first to awaken from his slumber, and he is the first to birth and bring death upon his comrades. Which, somewhat on the nose, eludes to Cain in Genesis, the firstborn son, the firstborn human from Adam and Eve, and he is shown to be a murderer of his own brother. He enacts harm to his own family, and those around him, and models death as an action he wields. Cain is associated with death in Genesis and serves as an archetypal model for Kane’s own association with death. The masculine association with the xenomorph is often clouded by the continuous comparison to the female body–it is the man’s body that in almost every movie produces the xenomorph/bodily invasion first. Even in Alien (1979) Parker, one of the crewmen, says, “This son of a bitch is huge! I mean, it’s like a man,” to which Ash, the ship’s android, responds, “Kane’s son.” This soft response from Ash not only solidifies the masculine association of birthing the xenomorph’s but also brings forth a consistent tension of man’s creation: the androids and xenomorphs.

Creating Man’s Seed

Creation throughout the Alien franchise is often associated with man. Man creates the androids who in turn further the creation and support of the xenomorphs who are a product of man’s desire to be creators and to know their creator. This is readjusting the creation blame from the woman onto a man for it isn’t a woman in Genesis who creates and aims to see like her creator. Eve’s eyes opened to see good and evil after consorting with the serpent and ingesting a fruit from the tree that not only brought Adam with her to their demise but man’s seed. Given the reverse roles, evoking the Genesis archetypal lesson, man’s desire for creation, the xenomorph and android’s, becomes man’s downfall. This is shown in every movie: it is the man first who is impregnated/brings forth the xenomorph rather than the woman, it is the androids–Ash and David–who aim to carry out harm towards humans to preserve the xenomorph’s existence, and the xenomorph brings forth anxiety that man’s creation cannot be controlled. Furthermore, as shown in Prometheus (2012), the first movie of the prequel series, Peter Weyland is shown to hold more interest in his android creation, David, than his own daughter, Meredith Vickers, to which Peter’s motivation to meet and mimic his creator informs David’s own drive to be a creator himself, the xenomorphs. The masculine aspects of the xenomorphs not only lie metaphorically but physically.

Xenomorph Serpent

It isn’t just the human figures and hosts that echo Genesis symbology and archetypal dynamics but the xenomorphs themselves. In Genesis, the ‘serpent’ is cunning, outside the norms of the other beasts that lie within the garden of Eden, and the only one who seems to challenge the bounds of humans, beasts, and God. This anxiety of boundaries that the serpent holds also exists in the xenomorph. The body itself is layered with phallic symbolism, from the protruding head, the secondary mouth that extends to violate its victim’s own mouth, and its penetrating tail. There is a continuous tension between the xenomorph’s body and the female body, which echoes the punishment God hails onto the serpent in Genesis 3:15, “And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel.” It isn’t just the seed of humankind versus the xenomorph that is in conflict but specifically the xenomorph and female protagonists. It is Elizabeth’s inability to birth her own human child that incites bodily invasion to birth a fully fledged xenomorph in Prometheus (2012) and is experimented upon for the evolving xenomorph creatures. It is Daniel's obligation to protect the ship, in Covenant (2017), which holds thousands of colonists and embryos that are in jeopardy to host the xenomorph’s ‘perfect’ form. And it is Ripley who not only tries to advance her superiority and right to motherhood above the xenomorphs in Aliens (1986) but it is Ripley’s DNA that aims to further the humanoid qualities of the xenomorph in Alien Resurrection (1997).

Such bodily interactions and exchanges between the xenomorph and women echo greatly the relationship of the serpent and Eve. However, time and time again this affords the women the burden of being the only ones to protect mankind from the xenomorph's invasion despite man’s desire to create, experiment, and control such an entity. The relationship between woman and non-human entities are seen as a threat to man and to faith; shown explicitly in the film Alien 3 (1992) as one of the prisoners, who has dedicated himself to a faith-based practice, says “we view the presence of any outsider, especially a woman as a violation of the harmony, a potential break in the spiritual unity.” However, the break in the spiritual unity between man and creator is not that of the female figures throughout the franchise but man’s creation itself.

Women’s Creation

Despite the clear evidence that shows that man’s demise is rooted in their own creation, the xenomorph is consistently pinned against the female figures throughout the franchise. The male characters and positioning of the narratives reassociate the xenomorph’s not as man’s creation but as women. In Prometheus (2012), despite the xenomorph existence stems from the human’s ‘creator,’ shown as a male-like figure, and David, man’s creation, imposing an unwanted pregnancy on Elizabeth’s partner–it is through Elizabeth’s consummation with her partner that produces the beginning of the xenomorph’s existence that she, in turn, extends the unwanted birth to the male creator body. While faith has been a theme in the prequel series (Elizabeth’s faith and cross necklace, and faith leadership in Covenant) the topic of gender dynamics, and positions of earthly than creator power dynamics were at the forefront of the narrative tensions. Ripley is often positioned with motherhood as an unattainable attribute–despite killing the xenomorph queen in Aliens and saving Newt, a young girl, Ripley is not rewarded with normalcy in Alien 3. E nuclear family dynamics held onto the fleeting ship in Aliens (Ripley, mother, Newt, child, Corporal Hicks, love interest) is destroyed in Alien 3; nevertheless, the temptation for normalcy is often waved in front of Ripley’s face. As the creator of Bishop, the android, offers Ripley a chance for a normal life and children, she rejects normalcy accepting that it is not truly an option for her. Her rejection of the possibility of normalcy is met by plunging herself and the xenomorph cub, pressed upon her breast to meet a fiery end. Ripley’s association as birthing the xenomorph, man’s demise, is cemented in Alien Resurrection as she is shown to have direct responsibility in birthing the xenomorph queen and a hybrid-human like a xenomorph. Ripley’s body is directly evoking categorical anxiety of engaging with the unknown entity, the xenomorph, the serpent, not just by being a host in their birth but her DNA isn’t just human but xenomorph.

Conclusion

There are a lot more elements to the Alien franchise that echoes and challenges Genesis' archetypal narratives. Nevertheless, it is this brief overview that aims to unveil and connect aspects of the Genesis Paradox that exists within the Alien franchise. The sci-fi horror genre exists to unveil the power and gender dynamics that exist on earth even if it is placed in a different galaxy, planet, or spaceship with xenomorphic alien lifeforms.

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)