[Editorial] Disability and Horror: Introduction

Within the world of horror films, disability representation has had a fraught history, but one I’ve paid careful attention to all my life. I was born with a rare disease that took half my hearing, half my vision, and half my face. As a child with a birthmark that enveloped the right side of my face and forced my right eye closed, I never saw people that looked like me anywhere in the world. I also couldn’t identify with the images I saw of people with symmetrical, unblemished faces. One fateful night though, the babysitter from across the street came over with her boyfriend, some weed, and a VHS of A Nightmare on Elm Street. I looked at Freddy Krueger and finally saw myself. I was only three, but I knew then I was the monster. A year later, my father let me watch all of the Universal Monsters. I never saw myself in the victims. I saw myself in the Phantom of the Opera. From narratives about disfigurement and monstrosity, I learned early on in my life that I would most likely only ever see myself represented in horror films.

Around the same time, my parents introduced me to the film Mask (1985), hoping that I’d receive some kind of positive message about where I fit in the world. The message I received was that society needed me to be some kind of saint to feel comfortable with the way I looked. The term “inspiration porn” hadn’t been coined yet, but that film was a perfect model for every film that dehumanizes people with disabilities by creating narratives that say that they are heroes because of their adversity, who belong on pedestals. I know that the same people who looked away when I turned to face them and never met my gaze were the same people who over time learned to suppress this urge for the more socially acceptable version of believing stories of inspiration and sacrifice. By putting me on a pedestal, they still never had to look me in the eyes, never had to recognize my agency or my humanity. Needless to say, I rejected this portrayal of the perpetually sweet and kind and inspirational Eric Stoltz in Mask in favor of the monsters, embracing them as my representatives of trauma, the avatars of my righteous anger at the world.

As time has gone on, my identity as a disabled person has grown and changed, as has my identity as a horror fanatic. As I began to suffer problems related to mobility, cancer, and heightened chronic pain, home invasion horror began to hold a special fascination. The idea that anyone can take over your surroundings and cross over into your personal space felt like what I was enduring any time I went out in a wheelchair, and someone came too close, or hung a bag on the back of my wheelchair. It also felt like the violation inherent in permitting other people to help me with daily tasks. I wanted bodily autonomy and I didn’t have it. My body was the house, invaded and taken over by too many entities at once. The horror of a home invasion narrative never comes from the moment of real violence, it comes from that moment when the threshold is crossed. My personal boundaries felt meaningless, but watching the barriers broken and then restored in horror movies restored my sense of order, if only temporarily.

As I acquired hearing aids for the first time, amongst other medical devices, my relationship to body horror became much more personal. The other was now a part of me, something I had to assimilate into myself and rely on to survive. I began to watch films exploring themes of medical or mechanical augmentation, such as the Tetsuo the Iron Man series or Meatball Machine (2005). In these movies, I found my fears and fantasies perfectly expressed. What new form of monster was I becoming, and what kind of control would these new devices wield over me?

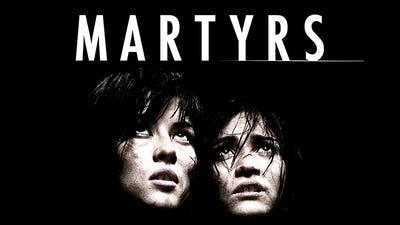

As new neurological conditions required me to have more and more spinal taps and surgeries, extreme horror became the closest I could come to validation of my lived experience in the outer world. The shocking nature of films like Martyrs (2008) became a source of comfort to me. I saw in the story of Lucie and Anna a portrait of my anguish but also a representation of what I saw as the transcendental nature of pain. I regarded my body as nothing more than a broken vessel in those moments of recovery, and found it all too easy to dissociate entirely. The only way I could feel and fight the deadening of the senses was to seek out the most gory, the most disturbing, the most gut-twisting and nerve-shredding horror I could find.

Through every aspect of my disability, I have found horror to be the only genre of film that gives me the catharsis I need, that represents my experience, albeit usually in metaphorical ways, and gives me the emotional tools I need to carry on with my day. At the same time, representations of disability onscreen have evolved considerably within my lifetime. No longer do I need to look to the same monsters with the same disfigurements as my only frame of reference for my own identity as a disabled horror fanatic.

In future editions of this column on disability in horror, I will be analyzing a variety of horror titles from different eras and countries that integrate disabled characters and/or important narratives about disability in their storytelling. My purpose here is not to debate every aspect of the overall merits of the movies I discuss as a whole. This site has many brilliant reviewers who can offer that commentary in detail. Instead, I intend to explore each title’s disability representation, what it means in the conversations within the disability community, and how it reads on a larger scale, as it is received by a global society still battling with many aspects of ableist ideology.

I’m enormously excited to dive into this research project with you, dear reader, where I will be looking carefully and eagerly at any feedback you provide as it continues. I hope you will log on for my first official column, which will run next month, when I discuss A Quiet Place Part 2 (2020) in depth. Until then, do good work and keep in touch.

When people think of horror films, slashers are often the first thing that comes to mind. The sub-genres also spawned a wealth of horror icons: Freddy, Jason, Michael, Chucky - characters so recognisable we’re on first name terms with them. In many ways the slasher distills the genre down to some of its fundamental parts - fear, violence and murder.

Throughout September we were looking at slasher films, and therefore we decided to cover a slasher film that could be considered as an underrated gem in the horror genre. And the perfect film for this was Franck Khalfoun’s 2012 remake of MANIAC.

In the late seventies and early eighties, one man was considered the curator of all things gore in America. During the lovingly named splatter decade, Tom Savini worked on masterpieces of blood and viscera like Dawn of the Dead (1978), a film which gained the attention of hopeful director William Lustig, a man only known for making pornography before his step into horror.

Looking for some different slasher film recommendations? Then look no fruther as Ariel Powers-Schaub has 13 non-typical slasher horror films for you to watch.

Even though they are not to my personal liking, there is no denying that slasher films have been an important basis for the horror genre, and helped to build the foundations for other sub-genres throughout the years.

But some of the most terrifying horrors are those that take place entirely under the skin, where the mind is the location of the fear. Psychological horror has the power to unsettle by calling into question the basis of the self - one's own brain.

On Saturday, 17th June 2023, I sat down with two friends to watch The Human Centipede (First Sequence) (2009) and The Human Centipede 2 (Full Sequence) (2012). I was nervous to be grossed out (I can’t really handle the idea of eating shit) but excited to cross these two films off my list.

Many of the most effective horror films involve blurring the lines between waking life and a nightmare. When women in horror are emotionally and psychologically manipulated – whether by other people or more malicious supernatural forces – viewers are pulled into their inner worlds, often left with a chilling unease and the question of where reality ends and the horror begins.

Body horror is one of the fundamental pillars of the horror genre and crops up in some form or another in a huge variety of works. There's straightforward gore - the inherent horror of seeing the body mutilated, and also more nuanced fears.

In the sweaty summer of 1989, emerging like a monochrome migraine from the encroaching shadow of Japan’s economic crash, Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man shocked and disgusted the (very few) audiences originally in attendance.

Whether it's the havoc wreaked on the human body during pregnancy, emotional turmoil producing tiny murderous humans or simply a body turning on its owner, body horror films tend to be shocking. But while they're full of grotesque imagery, they're also full of thoughtful premises and commentary, especially when it comes to women, trauma, and power.

The human body is a thing of wonder and amazement–the way it heals itself, regenerates certain parts and can withstand pain and suffering to extreme extents. But the human body can also be a thing of disgust and revulsion–with repugnant distortions, oozing fluids and rotting viscera.

This June we’ve been looking at originals and their remakes—and whilst we don’t always agree with horror film remakes, some of them often bring a fresh perspective to the source material. For this episode, we are looking at the remake of one of the most controversial exploitation films, The Last House on the Left (2009).

The year was 1968 and a young man named George A. Romero had shot his first film, a horror movie that would change the world of cinema and not just horror cinema, at that. Night of the Living Dead (1968), would go on to become one of the most important and famous horror films of all time as it tackled not only survival horror but also very taboo and shocking topics like cannibalism and matricide.

In the end I decided to indulge myself by picking eight of my favourite shorts, and choosing features to pair with them that would work well as a double bill. The pairs might be similar in tone, subject or style; some of the shorts are clearly influenced by their paired movie, while others predate the features.

RELATED ARTICLES

Films that blend horror with romance always fascinate me; add a niche contemporary setting that I’ve never heard of before and I’m hooked. Cannibal Mukbang was made by Aimee Kuge, a young woman from New York, and I was privileged to spend a little time talking with her over Zoom…

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.

In the six years since its release the Nintendo Switch has amassed an extensive catalogue of games, with everything from puzzle platformer games to cute farming sims to, uh, whatever Waifu Uncovered is.

A Quiet Place (2018) opens 89 days after a race of extremely sound-sensitive creatures show up on Earth, perhaps from an exterritorial source. If you make any noise, even the slightest sound, you’re likely to be pounced upon by these extremely strong and staggeringly fast creatures and suffer a brutal death.

Have I told you about Mayhem Film Festival before? It’s a favourite event of mine, so I’ve blurted about it in anticipation to many people I know. The event has just passed, so now is the time to gush its praises to those I don’t know.

Loop Track, Thomas Sainsbury’s directorial debut, has such a sparse description that it’s really difficult to know what you’re stepping into when it starts. It’s about Ian (played by the director), who is taking a trek through the New Zealand bush….

For a movie that doesn’t even mention the word “vampire” once throughout the length of the film, Near Dark (1987) is a unique entry in the vampire film genre.

If you like cults, sacrificial parties, and lesbian undertones then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the book for you. Samantha, a student at a prestigious art university, feels isolated from her cliquey classmates, ‘the bunnies’.

Kicking off on Tuesday 17th October, the 2023 edition considers the cinematic, social and cultural significance of the possessed, supernatural and unclean body onscreen.

I was aware of the COVID-19 pandemic before I knew that’s what it would be called, and before it ever affected me personally. My husband is always on top of world events, and in late 2019, he explained what was happening around the globe.

Metal and horror have many aspects in common. The passionate fanbase for both genres attend festivals and has created strong communities. Horror and Metal fans often sport clothing depicting their favourite bands or films, almost like a uniform.

EXPLORE

Now it’s time for Soho’s main 2023 event, which is presented over two weekends: a live film festival at the Whirled Cinema in Brixton, London, and an online festival a week later. Both have very rich and varied programmes (with no overlap this year), with something for every horror fan.

In the six years since its release the Nintendo Switch has amassed an extensive catalogue of games, with everything from puzzle platformer games to cute farming sims to, uh, whatever Waifu Uncovered is.

A Quiet Place (2018) opens 89 days after a race of extremely sound-sensitive creatures show up on Earth, perhaps from an exterritorial source. If you make any noise, even the slightest sound, you’re likely to be pounced upon by these extremely strong and staggeringly fast creatures and suffer a brutal death.

If you like cults, sacrificial parties, and lesbian undertones then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the book for you. Samantha, a student at a prestigious art university, feels isolated from her cliquey classmates, ‘the bunnies’.

The slasher sub genre has always been huge in the world of horror, but after the ‘70s and ‘80s introduced classic characters like Freddy Krueger, Michael Myers, Leatherface, and Jason, it’s not harsh to say that the ‘90s was slightly lacking in the icon department.

Mother is God in the eyes of a child, and it seems God has abandoned the town of Silent Hill. Silent Hill is not a place you want to visit.

Being able to see into the future or back into the past is a superpower that a lot of us would like to have. And while it may seem cool, in horror movies it usually involves characters being sucked into terrifying situations as they try to save themselves or other people with the information they’ve gleaned in their visions.

Both the original Pet Sematary (1989) and its 2019 remake are stories about the way death and grief can affect people in different ways. And while the films centre on Louis Creed and his increasingly terrible decision-making process, there’s no doubt that the story wouldn’t pack the same punch or make the same sense without his wife, Rachel.

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Getting sticky, slimy & sexy with body horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689072388373-T4UTVPVEEOM8A2PQBXHY/Society-web.jpeg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Editorial] They’re Coming to Re-Invent You, Barbara! Night of the Living Dead 1968 vs Night of the Living Dead 1990](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687199945212-BYWYXNBSH00C4V3UIOFQ/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+19.05.59.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Short & Feature Horror Film Double Bills](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687770541477-2A8J2Q1DI95G8DYC1XLE/maxresdefault.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] The Art of Horror in Metal](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695486401299-E5H2JNNJT26HKN0CI7WC/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.20.28.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

I can sometimes go months without having a panic attack. Unfortunately, this means that when they do happen, they often feel like they come out of nowhere. They can come on so fast and hard it’s like being hit by a bus, my breath escapes my body, and I can’t get it back.