[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.

The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) is one of the most popular horror films of all time. The image of the little girl walking backward down the stairs, projectile vomiting and stabbing her genitalia with a crucifix are truly disturbing. Whilst on the surface, the film is about demonic possession, there is so much more to the film than I had noticed on first viewing. When reassessing The Exorcist, there are implications of abuse brought on by Chris MacNeil’s reluctance to be a proper ‘mother’ to Regan. The Exorcist demonises Chris in some ways and at large is a film about the patriarchy. It also shows how the family becomes chaotic without a male presence as Chris is divorced and the house lacks a male figure. However, ‘The Exorcist’ (Father Karras and Father Merrin) save the household from the chaotic, unruly Regan.

The ‘Neglectful’ Mother

The Exorcist portrays the theme of child neglect. During the 1970s, as Pamela Wojcik rightly analysed in Fantasies of Neglect: Imagining the Urban Child in American Film and Fiction,

the concept of the negligent mother became synonymous with the feminist mother (108). The Exorcist’s Chris MacNeil is a divorced mother who seemingly “neglects” her daughter Regan for her career. A mother who put her career before her child became linked to the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s.

Career First, Daughter Second

The Exorcist can be read as critiquing motherhood of the 1970s by its portrayal of Chris. Chris appears to be a neglectful mother because she has the autonomy to work as an actress, which brings her a great level of independence. The scene illustrated in Figure 1. demonstrates that Chris is a career woman, as her work is very important to her which causes her so called “monstrosity”.

Figure 1. Chris MacNeil and her director Burke Dennings on the set of a film about student activism

The figure shows Chris with her film director Burke Dennings, with whom she has a close relationship. The relationship appears to be professional except that previously Burke had visited the MacNeil household at night. The late-night visit suggests a personal relationship. Regan’s questions suggest that Chris and Burke have a deeper relationship than what the film shows. Regan asks her mother, “You don’t love him like you like Daddy?” and “Do you want to marry him?”. This would be unsurprising, as Chris is a careerist, and she may have been having sex with the director to gain advantages in her career. In the 1970s, society feared that women were being more promiscuous because of the introduction of the birth control pill and access to abortions. Due to this perceived promiscuity, Chris could easily have had a sexual relationship with Burke without risking the consequence of an unwanted pregnancy. In Figure 1. Chris’s eyes are focused on Burke, implying that nothing else matters apart from her work. She is not watching the clock or showing any implication that she is worried about what her daughter is doing: she is focused on getting her work done. Chris had an important career, as evident in figure 1. as she talks intensely with the director. After Burke's death and the onset of Regan’s ‘possession’: Chris is forced to focus on mothering her child rather than her career.

Whilst Chris’s autonomy to work can be noted as liberating for women, in the portrayal of the film this is what leads to Regan’s downfall. As Reynold Humphries argues in The American Horror Film (2002), Regan’s possession seems to start once she is alone, whilst her mother is busy with her career as an actress. Other critics, like Barbara Creed, agree with this notion. Creed states in The-Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1993) that the major cause of Regan’s possession i s due to the declining mother-daughter relationship as a result of Chris’s work commitments. Despite the traditionalist views that a woman should invest all her emotional energy and her whole life into her children, more women were entering the workforce in the 70s. Mothers became the scapegoat for the collapse of traditional patriarchal society and the lives of their children. Karlyn Rowe states in Unruly Girls, Unrepentant Mothers: Redefining Feminism on Screen (2011), going to work instead of staying home with children was defined as an act of neglect. The public sphere of work and the world beyond the home was seen as the sphere of men.

Sexual Abuse

The Exorcist shows the neglectful mother trope as Chris leaves Regan open to child abuse. William Paul’s argument in Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy (1994) is that The Exorcist makes a powerful case against child abuse. In The Exorcist, Chris i s asked if the priest has been up to Regan’s room when she was not around and she responds, “he wouldn’t have any business going up to her room”. She does not question if the priest was in Regan’s room and if he was, what he was doing there, as it is very clear that he could have been abusing her. This would explain Regan’s outbursts of acts around sex such as masturbating with the crucifix and trying to rape her mother. How else would a young girl dealing with the strangeness of adolescence deal with the horrors of sexual abuse? The answer is simply that she would respond negatively, having outburst of violent acts and using vulgar language to all those around her.

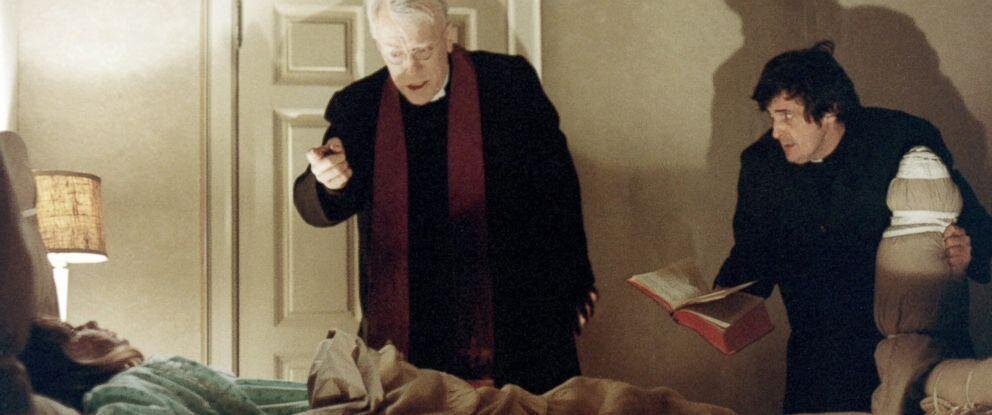

Figure 2. Regan's Exorcism carried out by Father Merrin and Father Karras.

Regan’s possible child abuse can also be read from a scene analysis of Figure 2. Regan’s positioning is interesting as her legs are spread apart. This position could be read as her vulnerability to sexual abuse. The image is disturbing because whilst she is in this vulnerable position, she has two adult men close to her. They appear to be almost dominating her with their prayers: she is their prey. The framing of the camera shows darkness surrounding the priests, whilst light seems to be radiating from Regan. The dark shadows on the priests could be seen as foreshadowing their sordid natures, despite being men of God, and their possible involvements in paedophilia. The two priests appear to be looking up Regan’s nightdress, which reinforces the Regan has been left open to child abuse by her mother who invited the priests into her home.

The Abusive Mother

The Exorcist also shows the abusive mother trope, which is a response to the feminist movement of the 1970s.

Abuse by Religion with ‘good’ intent

The Exorcist also uses religion as a means of abuse. Regan is regulated by religion (with ‘good’ intent), which can be seen as a form of abuse. The medieval-like method of Regan’s exorcism is reminiscent of an extraction of a confession from an accused witch to save her soul. Chris gives the priests permission to exorcise her daughter once she recognises that she threatens her social standing when Regan enters the dining room in front of Chris’s guests and urinates on the floor. Chris’s embarrassment is evident and she tries to justify Regan’s behaviour to her friends by saying: “I’m so sorry she has been sick. [To Regan] Regan, take your pills you’ll be fine”. Mothers’ concerns with the opinions of their bosses and co-workers could be read as problematic in the narrative of the self-sacrificing mother, who is supposed to live for and through her child.

Assuming the Worst in Your Child

Chris’s assumption that Regan was possessed is an illustration of her monstrosity, as it is ‘monstrous’ to assume the worst in one’s children. Chris concludes that Regan was possessed because of her socially unacceptable behaviour. Regan masturbated with a crucifix and urinated in front of her mother’s dinner guests. This does not ‘prove’ Regan was actually possessed. Regan’s behaviour may mean she is delinquent and attention seeking, but not possessed. In Aviva Breifel’s Monster Pains: Masochism, Menstruation, and Identification in Horror Films (2005), William Friedkin explains that Regan’s ‘disfiguration might come from something she did to herself’. With teenage delinquency on the rise in the 1970s, Regan’s cuts and bruises could be explained by her self-harming as a cry for attention from a mother who no longer cares, is no longer confined to the domestic sphere, and gives Regan no attention.

Parents assuming children were possessed became more frequent in society of the 1970s. After The Exorcist was released, there was more cases of demonic possession in the 1970s and Sergio A. Rueda questions in Diabolical Possession and the Case Behind the Exorcist: An Overview of Scientific Research with Interviews with Witnesses and Experts (2018) if this was a result of a new manifestation of the devil that had been ignored in the past. The increase of demonic possessions in the US after the release of The Exorcist is reminiscent of the growth of witch trials in the Early Modern period. After the release of Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (1487) – a inquisitor’s manual released to help assist the search for witches – there suddenly emerged thousands of previously unknown witches. Like Regan, who was behaving outside of the societal norms, women in the Early Modern period who deviated from their prescribed roles were not considered human: they were considered witches.

Some mothers saw ‘possession’ in their children, when they could not explain their child’s behaviour through rational means. An example of mistaken possession is the case of Annelise Michel, whose strict Catholic mother believed her to be possessed because Annelise had fainted at school, defecated in front of her classmates, and started hallucinating. These occurrences could have been due to many medical reasons or could have just been attention seeking tactics. However, her mother perceived these occurrences as a work of the devil and subsequently allowed Annelise to starve herself to death. Annelise’s last words were an illustration of desire for attention from her mother by crying “mother, I’m afraid”. Mothers assuming the worst in their children is problematic as Doyle states in Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers (2019), “Anna went looking for the devil and the devil is what she saw”. The supernatural elements are symbolic of the worst-case scenario by parents assuming that children are possessed instead of wanting attention from their parents. The supernatural elements in The Exorcist symbolise the attention Regan seeks from her mother. However, because of Chris’s liberal ways and assuming the worst in Regan, she is abused.

The film clearly demonises Chris showing her as too liberal, which in turn leads to monstrosity. However, this monstrosity in Chris, is reflected in her deviant daughter.

The Deviant Daughter

Figure 3. A Deviant looking Regan smiling

Regan having a divorced, working mother has a negative impact on her childhood. On the surface, the film presents Regan as possessed. However, underneath this, I really think the film is portraying working mothers as having a negative effect on their children. As discussed earlier, Chris is career-oriented, and this is synonymous with criticisms of the ‘feminist mother’ who cared more about her career than her children. The women’s liberation movement advocated for day care facilities, equal pay, and equal education to aid women to have better employment opportunities. Many critics, such as Joe Kincheloe, have said that more women in the workforce had negative effects on children who were given freer rein within domestic spaces. Kincheloe states in The New Childhood: Home Alone As A Way of Life (1998) as parents were still at work in the afternoon, when children got home from school, they were given the latchkeys and were expected to take care of themselves. Regan is a latchkey child who is doing everything in her power to get attention from her mother, whether by urinating on the carpet or masturbating with a crucifix.

Resentment towards Divorce

Chris’s divorce from Regan’s father has a negative effect on Regan. In the 1970s more women were seeking divorces, as Maria Montoya notes in Global Americans: Vol 2: since 1865: A History of the United States more than one million couples who divorced in 1975 alone’ (Montoya et al, 2018:784). Regan could be seen as punishing her mother for her failure to make the nuclear family work. This could explain why Regan embarrassed Chris in front of her dinner guests by lashing out with bad behaviour. Chris also seems to have a bad relationship with Regan’s father. This is evident as she constantly curses and berates him on the phone whilst Regan is listening.

Religious Iconography reinforcing the Patriarchal Order

The Exorcist includes many religious images such as crucifixes, priests, nuns, rosary beads, and statues of the Virgin Mary. Therefore, I believe that religious iconography shown is symbolic of the established traditional patriarchal order. Religious iconography contradicts that Chris is an atheist. Whilst The Exorcist supports and advocates Catholicism and tries to encourage individuals into having faith there are some contradictory religious scenes in the film.

Figure 4. Regan masturbates with a crucifix

Figure 4 shows Regan masturbating with a crucifix with her head turned 180-degrees, almost gazing at the viewer. Viewers may interpret this scene as religion literally screwing women because the image is of a little girl whose white nightgown is covered in blood of her own self infliction. This scene illustrates that the traditional order (motherhood and religion) is collapsing because her room is in disarray: lamps are broken, wall hangings are lopsided, and her bed is broken. This chaotic domestic space illustrates that Chris is being neglectful because she is not keeping her daughter’s room in order. Chris does not have her daughter in order either because of her masturbation. The nuclear family space is now a space of ruin.

In Reassessing The Exorcist, I have found that both the film and its imagery reflects the larger discussions about the motherhood role in society. The starkness of the images used in the film ensued discussions that motherhood had become reimagined irrevocably, which would lead to uncertainty in the future. The Exorcist also has something to say about ‘The Father’ and Fatherhood figures: the fatherless house signifies collapse and can only be rectified and brought to order by a male presence.

Works Cited

Anon. Life Magazine (March 1972). Wanda Adams dropout wife 3/17/72. New York: Time Life Inc, 34b-44.

Briefel, Aviva. (Spring 2005) “Monster Pains: Masochism, Menstruation and Identification in Horror Films” in Film Quarterly, University of California Press, 16-27.

Creed, Barbara. (1993) The-Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

Day, Elizabeth (2005) ‘God told us to exorcise my daughter’s demons. I don’t regret her death’ <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/1504158/God-told-us-to-exorcise-my-daughters-demons.-I-dont-regret-her-death.html> [accessed 18/07/2020]

Doyle, Sady. (2019) Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers: Monstrosity, Patriarchy, and the Fear of Female Power. Brooklyn and London: Melville House.

Humphries, Reynold. (2002) The American Horror Film: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Montoya, Maria et al (2018) Global Americans: Vol 2: since 1865: A History of the United States. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Rowe, Karlyn. (2011) Unruly Girls, Unrepentant Mothers: Redefining Feminism on Screen. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Rueda, Sergio A. (2018) Diabolical Possession and the Case Behind the Exorcist: An Overview of Scientific Research with Interviews with Witnesses and Experts. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.

Paul, William. (1994) Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gritt, Emma. (2017) ‘the Devil was in her’ haunting photos show ‘possessed girl who died after being exorcised and whose chilling case inspired a Hollywood move’,

<https://www.thesun.co.uk/living/4303767/anneliese-michel-possessed-photo-emily-rose/> [accessed 18/07/2020]

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Getting sticky, slimy & sexy with body horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689072388373-T4UTVPVEEOM8A2PQBXHY/Society-web.jpeg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Short & Feature Horror Film Double Bills](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687770541477-2A8J2Q1DI95G8DYC1XLE/maxresdefault.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] They’re Coming to Re-Invent You, Barbara! Night of the Living Dead 1968 vs Night of the Living Dead 1990](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687199945212-BYWYXNBSH00C4V3UIOFQ/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+19.05.59.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] The Art of Horror in Metal](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695486401299-E5H2JNNJT26HKN0CI7WC/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.20.28.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

I can sometimes go months without having a panic attack. Unfortunately, this means that when they do happen, they often feel like they come out of nowhere. They can come on so fast and hard it’s like being hit by a bus, my breath escapes my body, and I can’t get it back.