[Editorial] Mothers In Horror

Since its inception, women have always had a role in the horror genre. Early on, they were screeching and fainting damsels in distress, evolving later to ‘Final Girls’, a term coined by author Carol J. Clover in her work Her Body, Himself, which outlined the physical and mental characteristics that allowed them to be the last woman standing against a slasher’s often sexualised rage.

Society, for all the work and changes of the women’s liberation movement, the rise of feminism and equal rights, still views women in a particular way. In her book Featuring Females, Lynn Edith Paulson writes;

“The feminine nature of the patriarchal cultural ideology is rigidly reductionist: Women are the gentler, nurturing sex, earthily, most deeply fulfilled by the hearth and home, monogamous heterosexual partnerships, and of course, motherhood. (pg 133)¹

Women, as mothers, come with very specific connotations. That they will be loving and kind, good humoured and protective. That they, above everything else, will put the physical and emotional wellbeing of their offspring above their own. TNo matter what obstacle is put in their path, they will face it down with steely determination to save their children, even if it costs them their own lives.

However, the horror genre has never relied heavily on what is considered ‘normal’ or ‘traditional’. Instead, it focuses on the strange and macabre, the unknown and the abstract, the abject and the ‘other’, and the notion of motherhood itself - women as mothers, and the act of pregnancy and child bearing - makes it a fantastic area of society to be twisted into something dark and horrific.

The human body has often been used as a place for horror. Directors have delighted in using twisted limbs, wounds that ooze rancid pus and diseases that reshape the human form into something no longer recognisable to shock audiences. It should then be no surprise that pregnancy can be used to signify danger. A change is taking place within a woman’s body, hidden deep inside her as she grows a new life; the only external change visible is that of a bulging and ever-expanding stomach. Of this horror, Katherine J. Goodnow writes:

“Cells fuse, split and proliferate: volumes grow, tissues stretch and body fluids change rhythm, speeding up or slowing down. Within the body, growing as a graft, indomitable, there is an Other. And no one is present within that simultaneously dual and alien space to signify what is going on. (pgs 33-34)”

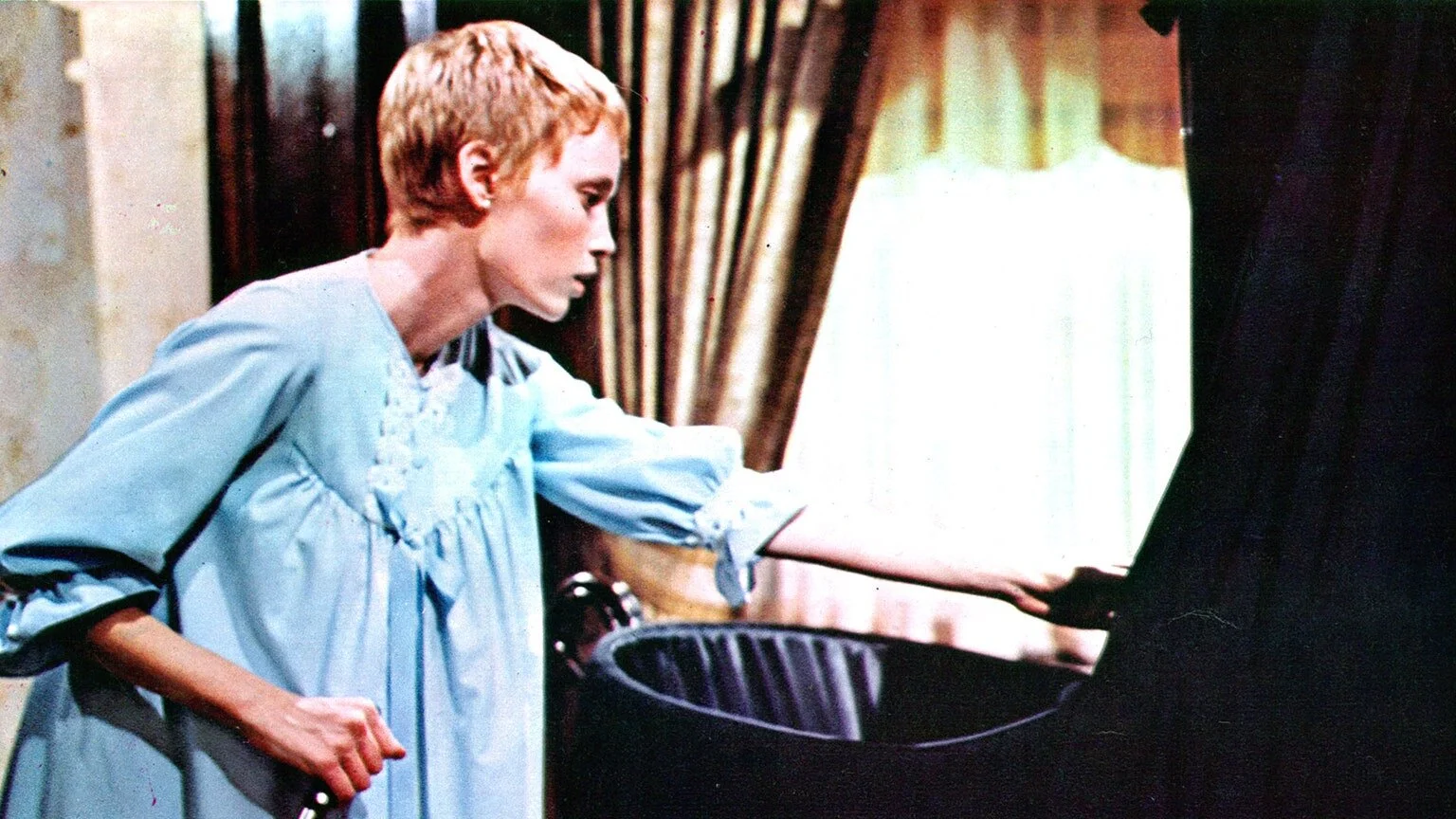

Rosemary’s Baby

The notion of the unknown and the unknowable is heavy here. Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow) experiences this first-hand, when she becomes convinced something is wrong with the child she is carrying in Roman Polanski’s 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby. Instead of growing and glowing, Rosemary withers and is racked with pain. Isolated, she cries and is manipulated by the doctor her well-meaning, tannis-brewing neighbours Minnie and Roman Castevete have recommended to her. It is normal to worry too much as women go through this every day. She should suck it up. Young and naive, Rosemary has one opportunity at a house party to confide in her friends, the young and hip crowd she once knew before beginning her maternity journey. They soothe her, listen, and urge her to seek help.

After the party, during a quarrel with her husband Guy about her ongoing pain, Rosemary states her deep fear that the pain is a sign that something is deeply wrong with her child, but she refuses to “get rid of it”. This is what the coven of witches who have hijacked Rosemary’s womb, using her desire for a baby and her husband’s selfish need for fame, are banking on. That a mothers’ love is eternal, unflinching and knows no bounds. Despite the apparently horrific face of her child, as the credits roll, Rosemary seems to accept her position as mother of the antichrist.

The nature of pregnancy for horrific purposes is used more overtly in scenes such as the dream sequence from David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly (1986). As Seth (Jeff Goldblum) continues his rapid evolution into part man, part fly, his lover, Veronica (Geena Davis), discovers she is pregnant. Aware that Seth has fused his DNA with that of a fly, she dreams that she gives birth to a dripping, writing maggot and opts for an abortion.

Pregnancy is fraught with worry and potential complications. The rate of miscarriage is one in four, and there is ectopic pregnancy and stillbirths to worry about as well as any number of birth defects. In both examples above, the pregnancy is made horrific by an outside force, the agency of both women removed from them by the men in their lives, leaving them and their offspring open to any number of potential future terrors.

Assuming that a woman hasn’t given birth to a monster, or the spawn of Satan, then comes Motherhood. In the early days there are sleepless nights, colic and teething to deal with. However, things are never that simple in the horror genre and can quickly (and for many varied reasons) spiral out of control. Mothers who were once loving and tender, for reasons beyond their influence, can change into homicidal maniacs, snarling beasts and terrifying witches. Women do not, cannot, turn violent for no reason. Paulson continues:

“We seek pre-emptive cause for female aggression that preserves the empathises on female victimisation.²”

She goes on:

“Women batter. Women kill their children and their partners. Women are serial killers operating for longer periods and claiming more victims before being apprehended compared with their male counterparts.³”

The Others

In The Others (dir. Alejandro Amenabar, 2001), the audience is led to believe until the very final moments of the film that Grace and her sun-sensitive children are living in a haunted house, being terrorised by unseen forces that go bump in the night. The events are seemingly set in motion by the arrival of a group of strangers claiming to look for domestic work in the midst of World War I. Already isolated by not only the war, but geographically, Grace is jumping, fragile and lonely as the story starts. The constant worry over her children has frayed her nerves. She is in a state of vigilance, highly strung and volatile. A woman on the edge, pining for her husband who is fighting overseas.

The house is indeed haunted, but it is Grace and her children who are the ghosts. Furthermore, their deaths were at Grace’s own hand. In a fit of grief and maternal madness, upon hearing of her husband’s death in combat, she drowns her two children and kills herself. Grace commits one of the most heinous acts society can imagine, one that many cannot comprehend, when she takes the lives of the children.

While this act occur off-screen and before the film begins, the audience are introduced to an attentive mother - so much so, that her own mental state has started to fracture due to the persistent worry. Mothers who kill their children are by no means unheard of, but receive so much more media attention due the sheer abjectness of the event. It goes against the very nature of what we are told a mother is, what she does and how she tends to her children. For a mother to go against what is considered ‘normal’ is completely abhorrent.

The Babadook

When Amelia (Essie Davies) loses her husband in a car crash on the way to deliver her son in the opening of The Babadook (dir. Jennifer Kent, 2014), it is an event so traumatising that she still struggles with it years later, as she tries to juggle work with life as a single mother. Her son, Samuel, is no easy child. Clingy and, prone to hysterics and screaming fits, the toll he takes on Amelia is easy to see. She is listless and drawn, struggles to sleep and has no life outside their dank and dark house. It is just her, her unruly child and her oppressive grief that seemingly seeps out and infects every aspect of her life.

Amelia’s waking nightmare of a life only gets worse when a mysterious book, entitled ‘Mister Babadook’ appears on her doorstep. The book sends the already fractured family unit on a downward spiral as they begin to experience strange sounds, which Sam blames on the Babadook. As things escalate, Amelia begins to experience violent fantasies in which she brutally murders her son.

All this escalates until she tries to strangle Sam, only stopping when he touches her face. Broken by her hallucinations, Sam is dragged away from her and Amelia is forced into a face to face showdown with the monster, confronting her consuming grief over her lost husband to save her child. For the family to move on together and be healthy, they must let go of the past, the what was and what might have been.

The film can be read in two ways- mother and son are either being stalked by a malevolent being, or, Amelia’s mental state has deteriorated to the point of a full-on breakdown. However, unlike The Others, this film ends with a note of hope. The pair are seen together, happy and smiling, making plans for the future. Amelia has successfully fought against her unnatural urge to kill her child and has emerged now able to be the mother Sam needs.

These are just a few examples of the many ways in which mothers are portrayed in the horror genre. From Margaret White’s abuse that triggers her daughter’s psychic powers in Carrie, to Mother Firefly, head of a murderous brood in House of 1,000 Corpses and The Devil’s Rejects, a mother’s love, her role in the family and in the lives of her children are far more varied than traditional mainstream media would have you believe.

¹ Paulson, Lynn Edith (2005), Featuring Females: Feminist Analyses of Media. American Psychological Association

² Paulson, Lynn Edith (2005), Featuring Females: Feminist Analyses of Media. American Psychological Association

³ Paulson, Lynn Edith (2005), Featuring Females: Feminist Analyses of Media. American Psychological Association

![[Editorial] Films To Ruin Your Day: Guinea Pig Series](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1654336384638-RERLWENSWVNSQKJSG0IZ/image5.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Film Review] A Wounded Fawn (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484054446-7R9YKPA0L5ZBHJH4M8BL/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.42.24.png)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] Perpetrator (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695483561785-VT1MZOMRR7Z1HJODF6H0/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.32.55.png)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Film Review] Sympathy for the Devil (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186986143-QDVLQZH6517LLST682T8/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.48.52.png)

![[Film Review] Mercy Falls (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695482997293-E97CW9IABZHT2CPWAJRP/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.27.27.png)