[Editorial] The Body as the Scene of the Crime: The Autopsy of Jane Doe and Reporting Sexual Assault

The Autopsy of Jane Doe is one of my favorite films of the last decade. It’s both terrifying and rich with deep meaning and social commentary.

Though director André Øvredal did not set out with this intention, his film is inherently feminist. It’s a cold look at the male gaze, a commentary on agency and female power, and a condemnation of the patriarchy itself. There are many readings of this fantastic film, but what has always resonated with me most is the way The Autopsy of Jane Doe so accurately captures the experience of reporting sexual assault.

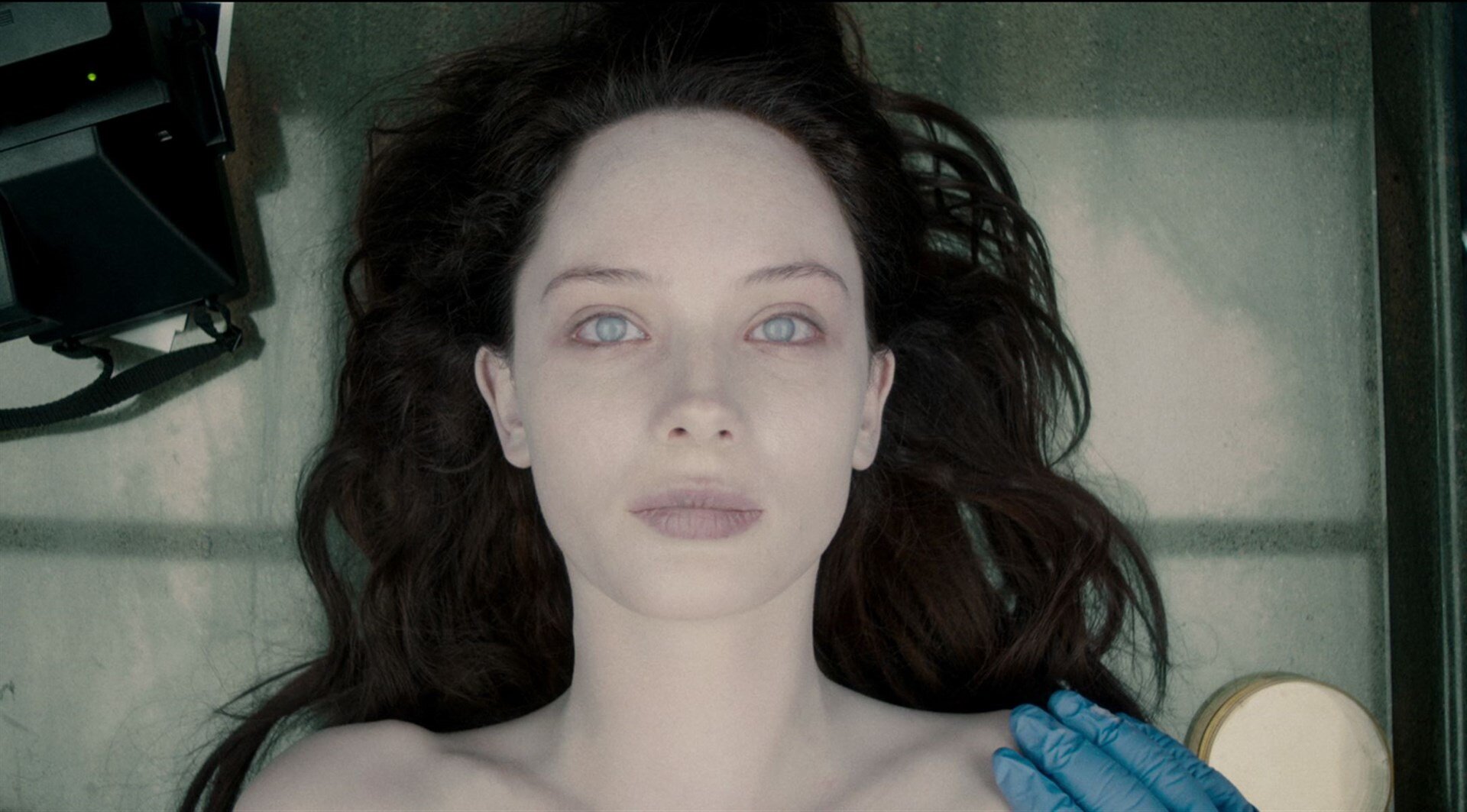

The film begins as Sheriff Burke finds a dead body buried under a brutal crime scene. Though nude, exposed, and partially covered in dirt, the body, called “Jane Doe”, looks perfect from the outside. There’s not a scratch on her and no apparent cause of death. Burke delivers her to the Tilden family mortuary where Tommy Tilden and his son Austin conduct an autopsy to determine how she died.

Jane’s body tells her story as Tommy and Austin cut her apart. We learn that she was the victim of extreme torture. Her tongue has been cut out, her wrists and ankles broken, her lungs burned, and her internal organs bear numerous wounds and lacerations. None of this is visible from the outside. Like the crime scene in which she was found, everything looks perfect on the surface, but the secrets lying within are horrific.

As Tommy and Austin’s work becomes increasingly invasive, strange things begin to happen in the mortuary. The power fails, mysterious figures appear in the halls, and the radio spontaneously plays an ominous song inviting them to “let the sunshine in.” Perhaps Jane does not want to tell her story on these terms. Maybe even in death, she doesn’t want her body poked and prodded, her skin peeled back, her ribs cracked open and tossed aside. But she has no agency. She is forced to lay naked on a cold table as she is talked over, cut, and examined; the atrocities she suffered crudely drawn on a chalkboard. The increasingly mysterious and dangerous events are her body's way of defending itself.

I empathize with Jane. In my early twenties, I was assaulted in a grocery store. I happened to be wearing a skirt that day and while shopping for fruit, one of the employees walked close behind me. I felt the brush and click of a phone on my thighs and instantly knew he’d taken a picture under the hem of my skirt. He walked away, but I knew what he had done. I still remember the way we locked eyes and I knew he knew too. I felt frozen in fear and shock. I didn’t know what to do. I continued shopping and tried to calm my nerves. I considered reporting him to management or calling the police, but I was afraid to make a scene. He was bigger than me and an employee of the store. Would it be safe for me to tell?

After paying for my food, I drove to another store and called the police. I waited in the parking lot and once the officer arrived, I began the process of reporting. I had to go back to the store and point him out. I had to tell this officer, a total stranger, what color underwear I was wearing, and then I had to hope that he would see a crude picture of it, thus proving that I had actually been violated. The store employee had deleted the image and claimed he routinely took pictures of weird produce which “explained” the camera sound I heard and felt. But I know what happened. I’m not going to try to prove my case here because you’ll either believe me or you won’t and I’m done trying to convince anyone that my pain is valid.

The officer told me that he couldn’t find any evidence. It would be difficult to prove, but I could press charges if I wanted. I chose not to. What was the point? It was unlikely anything would be done about it and in reporting, I would make myself a target. People in my life would know it had happened. So right or wrong, I chose not to file a report and I tried to move on. I continued to see this man at the grocery store for the next ten years. I’ll never know what happened to that picture. I like to think it’s been deleted, but nothing is ever truly gone. The knowledge of it lives inside me even if the pixels have disappeared.

Even writing this years later, I feel shame creep over me. I know I didn’t do anything wrong, but I still feel humiliated and violated. Like Jane, the process left me feeling exposed and powerless. Over the next few years, I was assaulted many more times. The details of those incidents are perhaps best left for another day, but they ranged in severity from physical assault to groping and rape. I didn’t report any of it. The one time I told my friend, she called the police on my behalf and I lied to them, saying everything was fine. As I look back, I wonder what would have happened if I’d made a different choice, but I can’t change it now.

I didn’t report because I’d been down that road before. I’d gone through the humiliation of telling my story only to wind up with nothing but more pain. If I thought it was hard for a stranger to see a picture of my underwear, what would it feel like for strangers to see pictures of my insides? So I just swallowed the pain and gave up hoping for justice. Jane has too and the events of the film justify this hopelessness. Once Sheriff Burke realizes how complicated her case is, he ships her off to be someone else’s problem. Is it any wonder she feels so much rage? If you’re going to rip us open to find out what happened, you’d better do something about it. If you're going to cause us more pain, at least make it count for something.

Are Tommy and Austin’s actions wrong? And what of Sheriff Burke? I believe they honestly want to help, but their attempts are misguided. They exist within a system that views Jane as a crime scene rather than a human being. She is a puzzle to be solved, not a person to protect. Yes, she is dead, but how different would it be if she were not? Would the act of reporting not retraumatize her? How much care is taken to protect survivors from their attackers and the public after they report assault? Tommy and Austin use other bodies in their care to scare and mock Austin’s girlfriend Emma without questioning whether these people would want their remains treated like a horrific side show or practical joke. If Jane had not fought back, would her body have been treated any different?

So what should we do to help? If Jane could tell her story, I imagine she would prefer her body not be displayed and recorded for these strangers. I imagine she would want to take back the power that was stolen from her. Most of all, she would probably want what I want; for it to stop hurting. Or at least for someone to care that it does. Tommy attempts to absorb this pain and experiences everything she’s been through. He’s no longer a witness to the suffering, he has become a victim of it too. Is this fair to Tommy? Probably not, but it’s not fair to Jane either. We’ve accepted that this was her fate so we resign her to bearing it alone. And her suffering is more comfortable for us to watch than Tommy’s because we’re conditioned to expect that women will suffer. But what Jane really wants is for someone to truly see her. Not for a collection of body parts, but as a once living, breathing person who experienced unthinkable pain.

Save for the faint scar on my left cheekbone, I look completely normal from the outside. If you saw me on the street, or in the grocery store, you’d probably think everything was fine and that I have a normal, happy life. And to a certain extent that’s true. But there’s a pain raging inside me. Like Jane, it’s printed on the inside of my skin and it hurts. My chance for justice is long past. Now all I want is for someone to know how it feels. For someone to know about the pain I went through and to hold space for it. To let me cry and let me scream and to stop demanding that I hold it all in to avoid making them uncomfortable.

I’d like to end this piece on a hopeful note. But I don’t know if I can. I write this not to dissuade survivors from reporting their assaults, but to explain why so many of us chose not to. I like the idea of letting the sunshine in, but first we need to define what that means. Tommy and Austin attempt to do this by literally opening up Jane’s body and shining a light on her pain. They think they are helping but she has no control and has given no consent. By letting their understanding of “sunshine” in, they literally rip out her heart and set her on fire. Maybe the real sunshine is the warmth of knowing someone else will help us carry the burden. We must learn how to hold space for the pain survivors feel, to let them express it in a way that doesn’t retraumatize them, and to fearlessly listen without trying to shape their stories into a narrative we deem acceptable. We need to let survivors show their pain on the outside even when it hurts us to look.

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Film Review] Sympathy for the Devil (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186986143-QDVLQZH6517LLST682T8/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.48.52.png)

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] A Wounded Fawn (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484054446-7R9YKPA0L5ZBHJH4M8BL/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.42.24.png)

![[Film Review] Perpetrator (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695483561785-VT1MZOMRR7Z1HJODF6H0/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.32.55.png)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Film Review] Mercy Falls (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695482997293-E97CW9IABZHT2CPWAJRP/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.27.27.png)

Throughout September we were looking at slasher films, and therefore we decided to cover a slasher film that could be considered as an underrated gem in the horror genre. And the perfect film for this was Franck Khalfoun’s 2012 remake of MANIAC.