[Editorial] A Nightmare to Die For: A Deep Dive of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare

On a rare, empty evening recently, I found myself looking for a slice of horror that was intelligent and engaging but that also contained a strong sense of nostalgia; one film immediately sprung to mind. Presented with the opportunity to see my most admired final girl and one of horror’s darkest villains, another bonus being that I need not worry about the process of becoming acquainted with the central characters. Searching my shelves and struggling to pick it out amongst the snuggly packed rows, I experienced a brief moment of panic. I had settled on this film and nothing else was going to cut it (pardon the pun)! It was entirely by accident that my eyes then met with the word ‘Nightmare’ and I grabbed at the box with both hands, my heart beating faster in delight (such was the level of thrill, I may have even clutched it close to my chest). This being my first revisit in a few years, I scanned the cover to take in the artwork and explore what ‘extras’ I might be able to enjoy after the main feature. It was in doing so that I discovered the films’ title was not in fact what I had been searching for: Freddy’s New Nightmare but Wes Craven’s New Nightmare! For me, this not only represents an amusing unconscious slip of the mind but more significantly this small error is indicative of how synonymous Freddy is across the franchise.

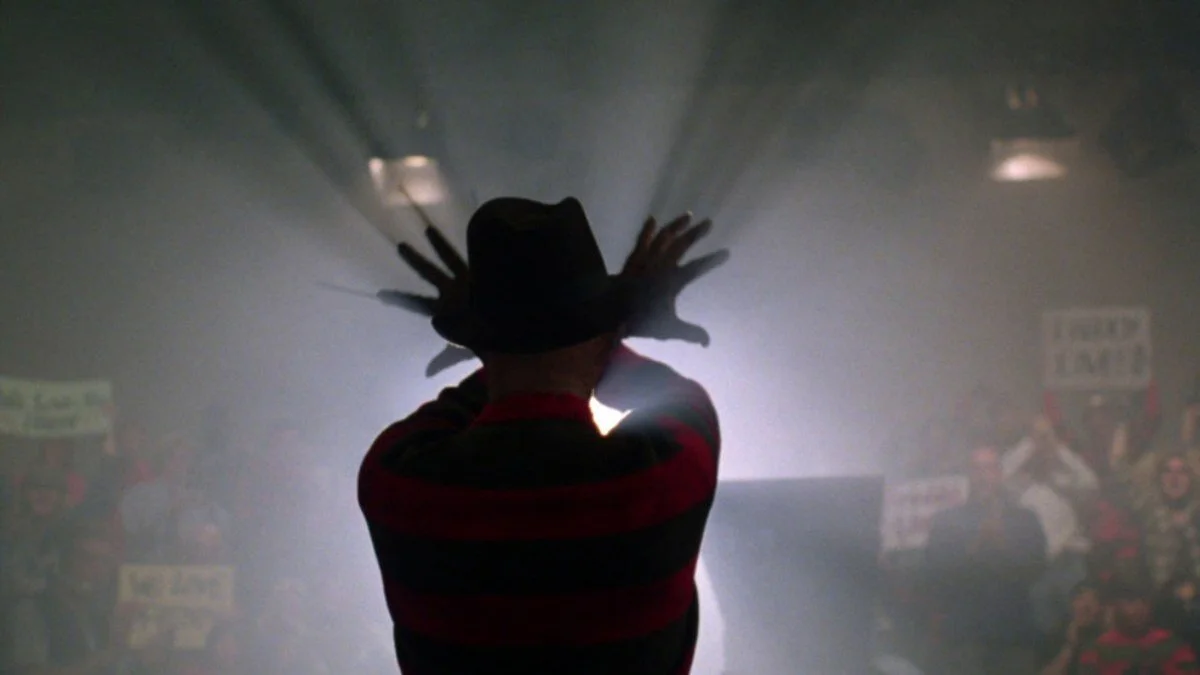

The Nightmare on Elm Street films would not exist without Freddy. Appearing in every outing in addition to the lacklustre 2010 reboot (see my article for Zobo with a Shotgun where I compared it to the original 1984 version), he is the face of the series and the face of all our nightmares. The fact that I as a horror enthusiast, had decided to temporarily erase Craven’s name from the title and replace it with Freddy’s is testimony to his enduring popularity and pervasiveness across the genre. Like the fans in New Nightmare who gather en masse after Englund’s appearance as Krueger on the chat show for an extra dose of Freddy, we too secretly desire the chance to see more of this horrifying yet fascinating character.

The Power of Two: Victims and Villains

Such points about Freddy, however, only serve to stand if we are examining the franchise as a whole. If we begin to separate the films and consider them on an individual basis then first Nancy and then Heather Langenkamp (playing herself, playing Nancy) become the natural central focus in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 3: Dream Warriors (1987) and New Nightmare. In terms of identification, empathy and screen time, she outsteps Freddy unequivocally and we see the world entirely through her eyes. However, it’s when the two characters appear together that the attraction reaches its highest levels; like watching Clarice and Lecter or Laurie and Michael, it’s seeing the victim and villain battle it out that is most dramatic and appealing. What’s striking about the relationship in New Nightmare between Freddy and Heather is how little has changed in their dynamic. By choosing to take up the role of Nancy one final time, Heather is immediately transformed into the strong willed and resourceful young teenager we recall from A Nightmare on Elm Street. In fact, such is the embodiment of her character on screen, I sometimes found myself sinking back to 1984 and believing her to be the youthful Nancy from all those years ago.

Fact, Fiction and Breaking Down the Fourth Wall

Although she may still have all the original strengths as Nancy, Heather also has the same fears and anxieties towards her old assailant. Freddy, who is not shown to be so inextricably linked to Robert Englund as Nancy is to Heather (in fact, in the end credits he is simply referred to as Himself) still retains all his power with the ability to manipulate his body in perversely horrific ways and now that he has made the crossover into the real world, he can emerge from the shadows at any given moment. Speaking of the magnitude of Freddy’s force and the tension this creates, Heather herself has remarked that: ‘It was interesting because all my scenes are kind of alone, and I was acting against this idea of Freddy that we all had at that time. We all knew what I was afraid of and that Freddy might be back’. Freddy is indeed the blanket of dread that covers the entire film and yet, he barely appears at all until the last twenty minutes or so.

When describing the process of writing the film, Craven commented: ‘I decided to have lunch with Robert and Heather, it was interesting from both how the movies had changed their lives, and they were imprinted with it, whether they liked it or not’. By combining their real-life experiences and portraying fictionalized versions of themselves, the director and his two leads are, as Langenkamp noted, taking their audience into: ‘a new special relationship with the real lives of people who act in these movies’ and essentially breaking down the fourth wall to reveal what is on the other side. Interestingly, Heather asserts that: ‘more of me is in Nancy than in Heather. Heather is this weird half-breed of, supposed to be me, supposed to be in a fictional story. And so, as a result, I don’t think I did invest her with as much of myself as I did Nancy.” Perhaps for Langenkamp, it was easier to give herself over to the character of Nancy as she was completely removed from her whereas playing the fictionalised version of herself felt too close, too personal.

Sleep Deprivation, Stalking and Suffering

If we take a look back to the origins of Freddy and thus the films themselves, we see that the backbone of the story is deeply entrenched in complex social questions. How justified the parents of Elm Street are in the burning to death of Fred Krueger (the man who victimised their children) is a matter for endless debate. The topics that Craven covers in New Nightmare range from stalking to grief and trauma. Although not a modern trend by any means, the notion of being followed by an unwelcome presence (and watching in 2021, this does not only mean in the streets) is at the forefront of all our minds. Whilst there is an added sense of horror to seeing Heather dealing with her stalker (an experience she unfortunately had to go through in real life), this inclusion also acts as an early alternative and unnerving precursor to the emergence of Freddy. In many ways the film demonstrates an underlying social conscience, not least in its portrayal of a mother and infant son working through bereavement and anguish. From the outset, it is clear that the impact of playing Nancy has weighed heavy on Heather and subsequently this has trickled down to her son, Dylan who even before the death of his father is clearly suffering. This is shown through sleep deprivation, a knowing nod to the original A Nightmare on Elm Street and Dylan’s need to have his cuddly dinosaur Rex protect him from the man he believes is at the bottom of his bed.

As the film evolves and Dylan’s family falls apart, his condition worsens and it becomes harder to identify how far his behaviour is attributed to his father’s death rather than to the dark cloud of Freddy that hangs over him and his mother. Heather meanwhile, in true Nancy Thompson style, is the constant warrior as she fights back with determination and perseverance in a world where she is for the most part, totally alone. The stress and the suffering which Heather endures is a very honest depiction of a single parent doing the best she can to look after her mental health in order to ensure the survival of what remains of her family.

Echoes of the Past: Homage and Revival

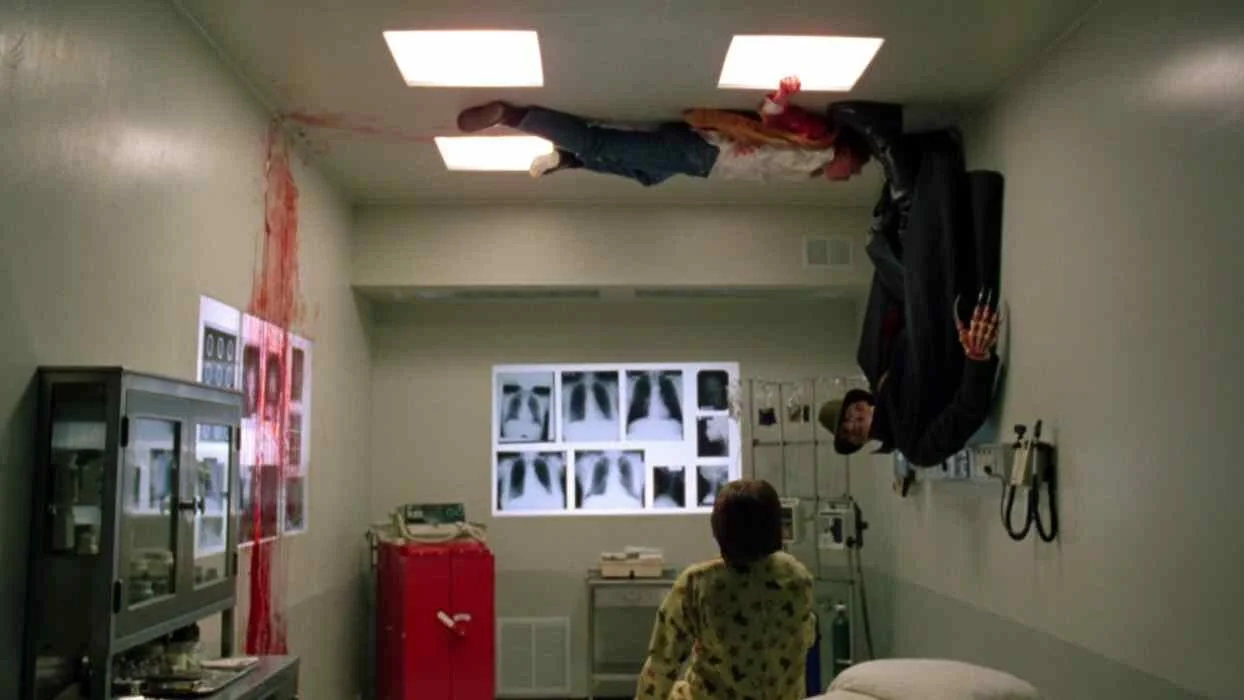

Fans are treated to a multitude of nods and winks that are tastefully achieved and rewarding, beginning no sooner than in the first scene which pays homage to the deeply unsettling intro of the 1984 film, showing Freddy creating his knife studded glove. Even this famous accessory has been given the update treatment with the knives appearing longer, sharper and more threatening than ever. Some references are subtle, such as Heather’s continuous consumption of coffee, including the reappearance of a percolator machine at her bedside, the revival of the ‘screw your pass’ line, a section of her hair turning grey and the furnace acting as a centerpiece near the film's closing. Others are near enactments’ of scenes from the original with slight twists; the phone from which Freddy’s tongue disgustingly protrudes to caress Heather’s face is not unplugged from the wall this time and Dylan’s nanny is dragged up and down the walls of what we suppose to be a safe space (the hospital), harking back to that unforgettable first death scene where Tina is murdered in what should be the safest space of all, her own bedroom.

Craven’s Creation: Reclaiming the Franchise

For all its freshness and ingenuity, New Nightmare was the lowest grossing film of the franchise. The director of what are generally considered to be the most favourable of the series (Nightmares 1 and 3), Craven had seen his original menacing Freddy descend into a hip and comedic figure, his child killer featured on lunch boxes in canteens everywhere and even having his own hotline that kids could have on constant speed dial. In one sense then, this was the director’s opportunity to reclaim his vision. In order to achieve this, Craven took a number of risks, some of which paid off and some by his own admission, that didn’t. With its focus on the psychological and lack of gore New Nightmare is more firmly rooted in the real world than any of the other films. The way Freddy looks however is perhaps the most significant change of all; he now wears a green hat and a dark, long trench coat making his physical appearance more imposing with a connotation of seediness.

A New Nightmare for a New Generation

New Nightmare has often been referred to as Craven’s training ground for the later, more commercially successful Scream(1996) which plays more heavily (and with much more finesse) with the multiple tropes that exist across the genre. However much in the shadows of it successor New Nightmare might now seem to loom, it’s worth remembering that it preceded Scream by two years and therefore deserves recognition for its vision of a new nightmare for a new generation. Craven masterfully combines an awareness of social issues that his Nightmare films were always sensitive to whilst also aiming to explore how our ability to separate reality from fantasy can falter. It’s this blurring of fact and fiction, what should and shouldn’t be trusted and whether we are dreaming or awake that has been a mainstay of the Nightmare series and it’s what makes them so plausibly frightening within the darkly imaginative world that Craven has built.

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

Possessor is a slick futuristic thriller in which Tasya Vos, an assassin for hire, must manage her responsibilities as an elite killing machine and complex feelings towards her husband and son, whilst taking on another high-profile job that will push her to the edge of her sanity.