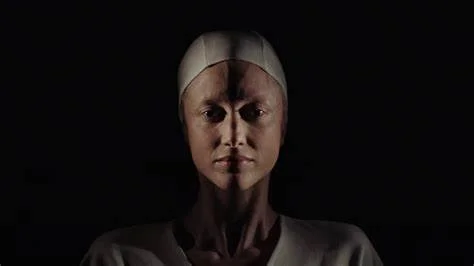

[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)

Possessor is a slick futuristic thriller in which Tasya Vos, an assassin for hire, must manage her responsibilities as an elite killing machine and complex feelings towards her husband and son, whilst taking on another high-profile job that will push her to the edge of her sanity. This is the second film from Brandon Cronenberg and we can see the Cronenberg pedigree on display from the start when Tasya manipulates a sickening intracranial implant in her current victim.

From the outset of the film, we see that Tasya is capable of brutal, bloody violence as well as the more sustained cruelty of taking over someone’s body to commit a crime before leaving them to deal with the consequences. But we also see that something is shifting for her, that she is losing control. Her boss—the enigmatic Girder—also notices this, and throughout the film we see how their toxically intertwined relationship is centred on Girder’s desire to control Tasya and bend her to her will. When Tasya loses control of the host body, she is weak and therefore a risk, when she deviates from the agreed strategy and explodes in an act of extreme violence, she demonstrates that she is losing control and may pose a threat to the careful corporate image Girder has meticulously crafted.

Throughout the film we see the liminal space Tasya occupies, during the first debrief sequence, her memory is not reliable, she is not a whole person any more. This is emphasised in how lightly she travels returning to her family home with no bags. Whilst outside, she practises being human for her husband Michael, mumbling a rehearsed conversation with herself. Once inside she watches her son Ira, programme a horrible puppet to dance, and it is impossible not to see this as an apt metaphor for her life. She has returned to bland, boring domesticity and, later, can only be excited by sex with Michael when she thinks of violence. After a short time, she decides to return to work and in this choice we see that liminality extends to her ambiguity between being a mother and an assassin, she’s nowhere and everywhere, she can’t be at home and can’t be at work. This creates an irritability that expresses itself as a desire to get started on the next job, to get away, get into another body. She only knows who she is when she’s playing at being someone else. The next assignment requires her to inhabit a man, Colin, to get to his girlfriend’s father, in a powerful act of corporate espionage.

In the first half of the film, we see the complexity, and duality, of Tasya’s circumstances. She feels guilt over killing a butterfly as a child but has no remorse about killing strangers for a living or using other people’s bodies to avoid detection. This speaks to the level of detachment Tasya has developed in order to fulfil her work although her motivations are never clear. We see that she loves (indeed craves) violence and is capable of acts of visceral brutality but at the same time, she moves as an automaton, unmoved by the events around her. When attending the party at her current target’s house, we see Tasya—inhabiting Colin— make a scene, in a calculated attempt to provide motive for the planned assassination. Tasya seems so out of control, so consumed by rage, but as soon as the door closes, she’s back to a blank. In this moment we understand that she finds freedom in playing with the emotions of others, in paddling in all the bitter realities of people, but she is unable to feel that depth of emotion herself.

The central premise behind Possessor is a captivating one. Through Tasya we can imagine what it would be like to wake up in a different body, to taste the inside of someone else’s mouth, to feel the weight of someone else’s hands and consider how hard it would be not to lose oneself in the shuffle. We see Tasya keep track of herself with her habits, how she cuts an apple for instance, and also that certain elements of her personality, her antisocial nature, remain. Possessor plays with the notion of reality and asks us to consider how real our reality is when so much of it is virtual. Whilst undercover Tasya has to manage Colin’s body in the same way he manages mundane tasks in virtual reality. The commodification of bodies is a prominent theme, Tasya sells herself via other people’s bodies, Colin engages in corporate voyeurism, everything is for sale in the world Cronenberg has built.

The notion of physicality, of gender, and the ability to breach the boundaries of the physical self are expertly manipulated in Tasya’s inhabitation of Colin’s body. We see that she is much more enthusiastic when having sex with Colin’s partner (when she sees herself with a penis) than during the mechanical sex with Michael. This plays with the notion of what it means to have a body and what our bodies can be. Tasya can be a man, a woman, both, neither, there are no constraints to her physicality. The inherent frailty of the physical form is further explored in Tasya’s craving for violence and her desire to beat, maim and bathe in blood. Body horror is in full effect, with gore being central to Tasya’s modus operandi. This violence also demonstrates the impermanence of bodies, how quickly they are wounded, crushed. We see Cronenberg’s indomitable style in the painful process of detachment from a body that’s not ready to let you go. Colin refuses to release Tasya, and she cannot escape his mind. Colin puts on Tasya’s face; he inhabits her body in a grotesque mirror of what she has done to him. He takes control, goes to her home to invade her life. The consequences of her actions bleed into her real, physical life, leading to the shocking, yet somehow expected, climax of Possessor.

Perhaps it is easier to see Tasya as a phantom, a non-corporeal being who slips into the hidden spaces we can’t access. By travelling through the hearts and minds of others, she sees behind the veil of physicality that keeps the rest of us rooted. Once that tether is severed, how far can one drift into the unknown. Once you have slipped another’s body on, like a suit of armour, how can you return to ordinary domesticity? When it is your job to inhabit the lives of others, to maim and kill for money, how do you reconcile that with queuing in the supermarket? For Tasya she must kill the past to look to the future. Tasya wants Michael and Ira gone, wants the shackles of her own life to be removed but she can’t do it herself, she’s a killer but she’s not a monster. When given permission, she exorcises her past in Michael’s blood before we see a screaming, righteous Tasya turn on Ira, ready to be free of him. Through the transgressive act of killing her son, she is freed from the last vestiges of her humanity. In her final act of manipulation, Girder inhabited Ira, knowing that Tasya would kill him. In this act, Girder has successfully created the uber killer, a Tasya free from any remaining tether to an ordinary life. We see in Tasya’s final debrief that she is irrevocably changed, that the previous tie to her humanity, the guilt over killing a butterfly, is gone. But we are left to wonder what becomes of a person who has lost all sense of self, and of humanity. What is left for Tasya in this new world?

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)

Possessor is a slick futuristic thriller in which Tasya Vos, an assassin for hire, must manage her responsibilities as an elite killing machine and complex feelings towards her husband and son, whilst taking on another high-profile job that will push her to the edge of her sanity.