[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer

Filmdom’s conventional wisdom in the mid-20th Century decreed that horror was no place for a lady. That is, unless it was as a shrieking victim dressed in a bosom-baring, diaphanous nightie. Few critics or filmmakers seemed to entertain the idea that there were women out there who enjoyed horror in their own right, rather than merely tolerating it as the price to pay for a Saturday night date with Mr. Right. The few women who worked in horror at the time were definitely trailblazers.

One such trailblazer—in her own quiet way—was Margaret Robinson, an accomplished British artist and puppeteer who worked behind the scenes on many of the most enduring horror classics produced by the legendary Hammer Studios. Born Margaret Carter in Louth, Lincolnshire in 1920, Robinson lived until 2016 and worked right up to the end creating art, before passing away at the age of 96.

She studied at several art schools, including the prestigious Slade School in London. While at Slade, she relocated with the school to the Ashmolean Museum of archaeology in Oxford during World War II. There, she took part in a project to make sketches and display replicas of the museum’s treasures, which were safely tucked away for the duration of the war. After leaving Slade, she did stints as an art teacher and a puppeteer/puppet maker for children's theatres.

Going to Work for Hammer

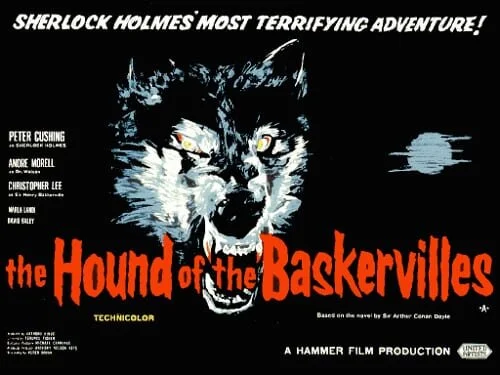

In the late 1950s, she moved back to London, and began to work in the film and television industry. She met her husband, Bernard Robinson, on the set of Hammer Studio's The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959 dir.Terence Fisher). Robinson was Hammer's long-time top production designer and Margaret was a member of the art department, hired specifically to make the demonic mask worn by the film's titular hound.

Bernard Robinson, who was essential to the famous Hammer “look", was known for being the master of the ”redressed” set. In other words, he used the same sets over and over with different furniture, wallpaper, drapery, etc. (many sets used in The Hound of the Baskervilles, for instance, were redressed sets from Fisher's 1958 Dracula). He made his productions look much more expensive than they were, given the miserly Hammer set budgets with which he was forced to work. Margaret's artistry and crafting helped him achieve that goal.

Bernard hired his wife to work on many of the studio’s most highly regarded films, including The Mummy (1959 dir.Terence Fisher), The Curse of the Werewolf (1961 dir.Terence Fisher), and The Brides of Dracula (1960 dir.Terence Fisher). For The Mummy, she made a series of Egyptian masks, and for The Curse of the Werewolf, she made gargoyle figures. For The Brides of Dracula, she made flying bats and a pair of very tall, imposing griffins for a library/study set.

Robinson retired from film work after the early sixties to raise her son. By that time, she and Bernard had moved to Chertsey, Surrey. Bernard unfortunately passed away in 1970 at the age of 57, but his wife lived in Chertsey until her death in 2016.

Helped Keep the Hammer Flame Alive

In her later years, Robinson became an important resource for academics, documentarians, and writers who were researching Hammer's films. She generously shared her experiences with horror historians, on DVD/Blu-Ray commentaries, and in several documentaries.

These documentaries include BBC's Timeshift: How to Be Sherlock Holmes: The Many Faces of a Master Detective (2014), where she recalled her time on the set of The Hound of the Baskervilles, starring Peter Cushing as Holmes. Robinson told the BBC that when she made the frightening mask for the eponymous hound, a large Great Dane named Colonel, she was afraid of the dog, because he had a reputation as bad-tempered and a biter. Colonel, however, took a liking to her, and would only allow Robinson, alone of all of the crew, to put the mask over his head. She had to remain on set in every scene featuring Colonel, hiding from the camera behind rocks and bushes.

She crafted Colonel's mask out of latex and rabbit fur, and oddly, she wasn't particularly proud of the piece. Robinson told Timeshift, "I was rather ashamed of that mask. I thought it was the worst mask I had ever made, and yet, it's the only one that people know about." Another fascinating fact she revealed about the film was that in the climactic scene where Colonel attacks Sir Henry Baskerville (Christopher Lee), a miniature set was constructed and much of the scene was shot with a boy stand-in dressed in a replica of Lee's costume.

"This was to make the dog appear larger," according to Robinson. Unfortunately, Colonel didn't like boys, and he tried to attack Lee's stand-in for real. A quick-thinking crew member rescued the child in the nick of time.

Sadly for film fans, after Bernard died early and unexpectedly in middle-age, Robinson elected not to return to movie work. She instead served as an art instructor at several art colleges and also as an art therapist in a psychiatric facility. She became a member of a well-known painter's group called the Chertsey Artists, and some of her work is collected by the Chertsey Museum. She taught art until full retirement at age 73, and she was known for her willingness to mentor younger artists and her general kindness.

Marcus Brooks, who maintains the official website for the Peter Cushing Appreciation Society, was a friend of Margaret Robinson's, first meeting her in 1979. In a memorial post, he remembers her as, "Always light, unpretentious and extremely kind; she had a no-nonsense approach and much empathy for young people and the arts."

Sources:

BBC, Timeshift: How to Be Sherlock Holmes: The Many Faces of the Master Detective (2014)

Exploring Surrey's Past: Margaret Robinson 1920-2016

Peter Cushing Appreciation Society, Blog Post (2016)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

Possessor is a slick futuristic thriller in which Tasya Vos, an assassin for hire, must manage her responsibilities as an elite killing machine and complex feelings towards her husband and son, whilst taking on another high-profile job that will push her to the edge of her sanity.