[Editorial] Florence Welch’s Ode to Female Monsters

A man stands distraught in an austere office as the beat begins. Suddenly, Florence Welch, dripping in her signature ethereal-witch attire, appears in the window as if by magic. When they make eye contact, she violently drags the man toward her with her mind, carrying him away from this barren place into one of her own making—one that does not allow for men like him.

A suited man, an alluring witch, bloody swords and self-mythology—these are the makings of a wicked woman—one who can’t control her ambition and won’t let anyone get in her way. The song and music video I am King from Florence + the Machine’s upcoming album, Dance Fever use female monstrosity to illuminate Welch’s tumultuous relationship to music and song writing.

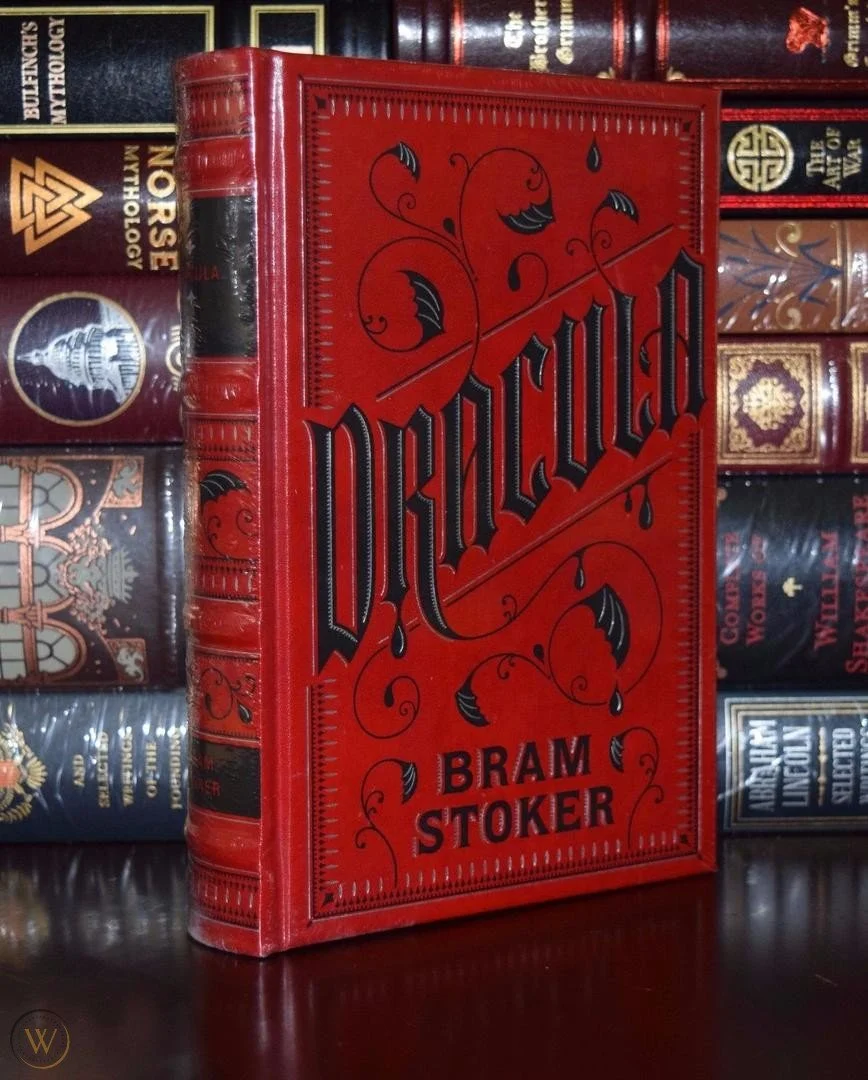

The song’s visuals and lyrics directly reference female monsters throughout history. To begin, one only needs to look at Lucy Westenra from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). I am King starts with, “We argue in the kitchen/ about whether to have children/about the scale of my ambition.” Here, Welch laments and considers the importance of music and career in her life, especially as they affect other personal goals often associated with womanhood, like raising a family. The location of the kitchen is also poignant—it’s the place where Welch is meant to be but refuses to occupy.

This is where her connection to Westenra begins. In his novel, Stoker uses Lucy to show the denigration of English society by foreigners—an obviously jingoist and racist aim, but that’s how a significant portion of early horror works. In the novel, Lucy starts out as an innocent, albeit flirtatious girl who resembles the sun and has her pick of suitors.

After Dracula has her in his clutches, though, she transforms. First, she becomes very sick before subsequently dying. When the men in her life suspect she’s a vampire after several children in the area are found drained of blood, they wait at her grave. She appears, sucking the neck of another child. Lucy is a literal vampire, but the depths of her new immorality are expressed through a distinctly feminine loss related to a violent rejection of motherhood.

It’s important to note that, in life, Lucy expresses difficulty in choosing her betrothed, commenting that she wishes she could have all of them. This is Lucy’s ambition that Stoker punishes. She already teeters on the edge of aberration, having love and passion that is beyond the Victorian woman. Becoming a vampire replaces her lust with bloodlust—marking her as a demon.

While there’s no doubt that Lucy is evil, it’s how she’s evil that generates interest. In FTM’s song, Welch sings, “I am no mother, I am no bride, I am king,” which cements her decision regarding the aforementioned argument. Welch’s ambitions are artistic and career-driven; she’s willing to give up a stereotypical household fantasy and, possibly, romantic relationship in favor of her dreams.

This likens her to Lucy and she knows it. Lucy literally feeds from children—flipping the common narrative of the mother sustaining the child. Second, when Arthur, Lucy’s fiancée, approaches her, she tries to coax him with kind words. Of course, she no longer has any intention of marrying him. She uses her new power (which includes beauty and persuasion) to try to feed from him. Welch plays with this concept of the independent woman as monstrous throughout the video—turning herself into a flying witch who breaks men’s necks with her mind. However, while Stoker villainizes Lucy, Welch’s song brings forth a certain sense of power. Welch as the witch has super strength, a palace and an army of dancing women following her around. She might be a monster, but that isn’t such a bad thing.

Similar themes can be found in Jennifer’s Body, a 2009 horror flick starring Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried. While Welch and Stoker focus on issues of art and nationalism, respectively, Diablo Cody uses Jennifer’s Body to study female sexual ownership in a man’s world. Lead character Jennifer Check becomes a demon and literal “man eater” after a botched satanic sacrifice, using her sexuality to lure boys to their deaths.

The visuals from I am King are less violent but have a similar air. At the end of the video, they’re back in the office, the man still alive. He runs to Welch and she consumes him, her cloak covering his head. The idea of the succubus, man eater, etc., dates back hundreds of years.

The fears around succubi are various but they fall into an overlying theme—women aren’t meant to understand or, God forbid, own their sexuality in a patriarchal world—only monsters do that. As with Lucy, Jennifer Check isn’t good, and the film doesn’t try to make that claim. However, the story does grant that, when it comes to killing boys, Jennifer has a point. She becomes a demon because a group of power-hungry men mistake her for a virgin and, in a scene heavily coded as sexual assault, they stab her. Monstrosity and sexuality save her, granting her superhuman strength and vitality.

In I am King, the narrator never claims to be a good person either. She sings, “But a woman is a changeling, always shifting shape… What strange claws are these, scratching at my skin/ I never knew my killer would be coming from within.” The first part of this quote plays into the idea that women are meant to fit into boxes that men control. Often, women adapt to fit these roles to survive. Jennifer doesn’t do much to hide her demonism, but she puts on charades to eat men—playing into their fantasies to meet her own goal.

HAVE YOU LISTENED TO OUR PODCAST YET?

In the context of I am King, Welch sings about her partner’s inability to grasp her, both literally and figuratively, as she is driven by something outside herself (her music) and, also, on a more elevated level, moving along a path not designated for women. She surprises her partner, her audience and herself by pursuing these dreams that are not meant to be her own. Jennifer Check exemplifies the second half of the quote completely—a monster inhabits her body. We can use this imagery to understand I am King better as well. Music is a killer that controls Welch, while simultaneously making her more powerful.

Also, through the trope of the tortured artist, men are allowed to be individuals with complex inner lives and inner demons that live through their work. However, in contrast to this, women are supposed to exist for others—as innocent mothers and brides. So, when Jennifer asserts, “I am a god” or Welch croons, “I need my golden crown of sorrow/My bloody sword to swing/ Need my empty halls to echo with grand self-mythology,” they are monstrous—abnormal. Both the song and the film establish the need for women to be complex, to have the freedom to be immoral and “evil” in the same way male artists do.

Finally, I am King reflects several themes from Ari Aster’s film Midsommar (2019). The movie centers on a group of American students visiting a blood-thirsty Swedish cult in the country’s remote hills during their summer celebration. Dani, played by Florence Pugh, joins her emotionally unavailable boyfriend and his group of insensitive grad school friends on the trip and, through several traumatic experiences and shared grief, becomes part of the cult. While the film falls under the slasher/cult horror genres, Aster has stated that it’s an allegory for a breakup. Dani’s boyfriend dismisses her emotions, gaslights her and, ultimately, cheats on her with a girl from the cult. Aster conveys Dani’s pain with a profound empathy, presenting her choice to stay with the monstrous cult as an act of self-love rather than viciousness. Still, though, it’s difficult to get past the image of her boyfriend, paralyzed in bloodied bear skin, as he burns in a sacramental tent.

Dani rejects everything that’s expected of her. The audience thinks she’ll be distraught on the trip, the greatest outsider of them all. Instead, she becomes part of the culture—taking solace in a world that’s cruel, but sensical. There’s no reason her boyfriend treats her poorly or why her sister kills her parents, but she knows that the cult kills to protect its culture, participates in consensual senicide as an end to a life cycle, etc. The cruelty has an underlying logic that Dani craves.

Welch justifies her toxic relationship to music through similar means. Dani is drawn to this strange group because of her trauma and several confounding circumstances. For Welch, it’s an involuntary drive. She concludes the song, “I was never satisfied, it never let me go/ Just dragged me by my hair/And back on with the show.” Welch differentiates the song as a separate, more menacing monster distinct from herself.

It seems difficult, even irresponsible, to categorize Dani as monstrous. In many ways, she’s the most sympathetic—she goes through so much and still faces adversity. She, like Welch, suffers from a lack of control. The music drags Welch along and manipulates her—forcing her to behave destructively. The cult takes advantage of Dani’s grief, using it as a way for her to join its folds. However, even if it doesn’t seem like it, Lucy and Jennifer are just as innocent. Female monsters rarely deserve all the blame.

Women exist in a world that seeks to control them through manipulation—if they reject this lifestyle, like Jennifer Check or Lucy Westenra, they’re called harlots and succubi. If they go along with it, like Dani, they force society to see itself for what it is—the true monster. As a result, those like Dani must be villainized, otherwise patriarchy crumbles. In I am King, Welch sits somewhere in the middle, encompassing both forms of female monstrosity.

At the end of Midsommar, we see Dani covered in a garden of pulsating, psychedelic flowers as she sneers at the burning tent. I am King offers stunning visuals, lingering lyrics and a catchy beat. These works force the audience to partake in female monstrosity as beauty, as truth.

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Bay (2012) with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Amber T](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1684751617262-6K18IE7AO805SFPV0MFZ/The+Bay+website+image.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682536446302-I2Y5IP19GUBXGWY0T85V/picnic+at+hanging+rock.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Psychotic Women in Horror with Zoë Rose Smith & Mary Wild](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678635495097-X9TXM86VQDWCQXCP9E2L/Copy+of+Copy+of+Copy+of+GHOULS+PODCAST+THE+LOVED+ONES.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Nekromantik with Zoë Rose Smith & Rebecca McCallum](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1677422649033-Z4HHPKPLUPIDO38MQELK/feb+member+podcast.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 5 & Wrap-up with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841326335-WER2JXX7WP6PO8JM9WB2/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%284%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 3 & 4 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841151148-U152EBCTCOP4MP9VNE70/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%283%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Final Destination 1 & 2 with Ariel Powers-Schaub & Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841181605-5JOOW88EDHGQUXSRHVEF/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%282%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841247731-65K0JKNC45PJE9VZH5SB/PODCAST+BONUS+2023+%281%29.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] A Serbian Film with Rebecca and Zoë](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1672841382382-RY0U5K7XD4SQSTXL2D14/PODCAST+BONUS+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667061747115-NTIJ7V5H2ULIEIF32GD0/Image+1+%285%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] How I Love to Love Nadine in The Stand (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690213172707-TKM9MZXK02EVCIX30M1V/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+16.29.11.png)

![[Editorial] 11 Best Werewolf Transformations in Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689240234098-HUPQC6L57AAHFJNT8FTE/Screenshot+2023-07-13+at+10.09.13.png)