[Editorial] Reviving Freddy: A Critical Reassessment of Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare Part 2

Enough with the Backstory!

Backstories for villains in horror films are divisive, they can be illuminating for some. but for others, the mystique should be left untampered with as the true horror is either that which resides within your imagination or the totally unknown. In the documentary Never Sleep Again which looks at the history and making of the franchise, Talalay revealed that in choosing to kill Freddy (at least, temporarily) she felt Freddy’s Dead owed the character a deeper look into the context of his behaviour. In choosing to explore this, Talalay makes a risky decision, but does it pay off? The history of Kruger is told through the use of flashbacks realised as Freddy’s memories which show him at various landmark points in his life. This is illustrated by depicting a hallway containing numerous doors, giving more than a gentle nod to Freud’s theory of doors representing a repression of an event that has been seen, misunderstood and has therefore been in some way traumatising. As a young boy, Freddy brutally murders the class pet with a hammer. In a foreshadowing of his famous red and green costume, he is seen wearing a striped tank top of the same colours as his classmates gather behind him chanting ‘son of a thousand maniacs’, another reference, this time to the original backstory. This brief scene provides us with two pieces of information; 1) that Freddy was a psychopath from an early age (harming animals is a trait used to distinguish Psychopathy and 2) that as a result of this he was ostracized from an early age.

In another room we flash to a teenaged Freddy standing in a garage slashing, not others, but himself. His self-harm is interrupted by his foster father played by Alice Cooper to whom Freddy addresses directly: ‘you want to know the secret of pain? If you just stop feeling it, you can start using it’. We learn that Freddy was abused by his foster father and now, almost a man, he unleashes his vengeance upon him. While this information does not excuse Freddy’s behaviour in the future, it adds an interesting contextual layer. Within the next room, we see an adult Freddy being chased and burnt by the parents of the Elm Street kids as the three snake monsters taunt him, feeding on his wickedness. Finally, we see Maggie crawl up from a basement and out into the last memory of Freddy attacking her mother for ‘snooping in my special workshop’. We are back in the American idyl that Talalay has drip fed us throughout the film. However, this time rather than showing us the mother promising Freddy ‘I won't tell’ (as we have seen before) we see that it is now Maggie (originally named Katherine by her parents) who is asked not to reveal what she has seen. As she struggles to fight back the tears, the little girl in the dress with ribbons in her hair promises not to tell. Read on the surface this situation looks hopeless, Freddy has murdered his innocent wife and a young and defenceless infant is powerless to change the situation. However, Talalay inserts a beautiful twist that gives control to the victim when Freddy appears behind adult Maggie in the present day and we find out that she did not keep the secret: ‘you did tell, didn’t you?’

Even once Maggie has seen this backstory, she is not cajoled into feeling empathy for Freddy, despite him employing her: ‘you saw what they did to me as a child’ ‘I tried so hard to be good’ which signals to audiences that they should also not be softened by Freddy’s past. While it is understandable to question the value of the addition of a Freddy backstory, it could be argued that, with Talalay’s approach, it can to a certain degree, be read as a means of us further enriching our understanding of Maggie. By placing the power back in the hands of Maggie, Talalay turns the function of the backstory from a ploy to feel empathy for a villain to a means of creating an authentic and ultimately victorious journey for her protagonist who avenges the death of her mother.

A Freddy of Many Faces

The idea of Freddy as duplicitous and assuming many faces is introduced from the film’s first moments. With a cartoonish-ness that foreshadows the role played by Jim Carrey in The Mask (1994), Robert Englund (playing himself) appears as a ticket seller on a roadside and then as Freddie driving a truck as John is thrown from the dream world to the real one. Freddy’s likeness is also embodied in the statue which stands proudly in the centre of Springwood, bearing the caption ‘The children shall endure’. The fact that this statute vaguely resembles Freddy is disconcerting as a) it would be inappropriate and totally jarring if it were an exact replica and b) by partly assimilating Freddy (the statue is a man with a slender silhouette and a prominent hat) it prompts the viewer to become a constant scrutiniser of the mise en scene by maintaining the need to keep a watchful eye out for any sign of Freddy who literally could be, anywhere.

He also inhabits the appearance of people who have caused the most damage in the lives of the teenagers, morphing into Carlos’ overbearing mother and Tracy’s abusive father. The latter particularly hard hitting as we watch Tracy face her demons, beating her father with a kettle before he shape-shifts into Freddy whom she tells assuredly, ‘this is my dream and I do what I want’. Furthermore, Freddy appears as Tracy to the Doctor back at the shelter and teases him whilst performing cartwheels and declaring ‘you’ve taught me a lot but you’ve still got a lot to learn’. When John Doe and Maggie visit Springwood School to find out more they are met with an oversized chalk drawing of Freddy complete with fedora, striped sweater and glove, a confirmation that the mythology of Freddy began in the playground before reaching far and wide to be presented in different formats, transcending time and space.

Straying from the Formula

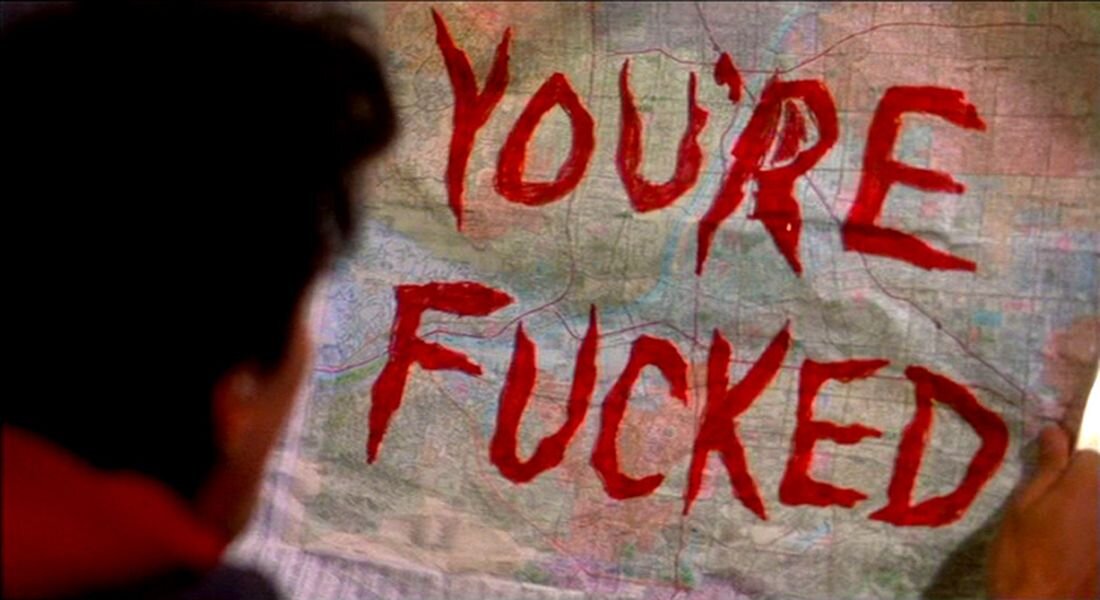

Freddy’s Dead unquestionably strays from formulas of the more critically well-regarded Nightmare Films and whether it was Talalay’s intention or not, it sits more comfortably in the comedy genre than the horror one. In switching up Freddy’s backstory, by choosing to be self-referential and in having a female character don the symbol of Freddy’s power, his knifed glove, Talalay takes some bold risks. Its campiness can be grandiose and over the top at times but in a franchise where dreams (and nightmares) are fundamental, the surrealism can work in the film’s favour such as when Tracy asks Carols for a map when they keep navigating in circles. Carlos is positioned at the back of the van whilst Tracy and Spencer sit upfront. We are shown what the two friends are not; an ever- exasperated Carlos pulls out the map over and over again as it keeps growing until it consumes the back of the van. Finally, he reaches a readable section which reveals the words ‘you’re fucked’ in large, Freddy-red letters.

The inclusion of the snake monsters who roam the dreams of the living to ‘find the most twisted human imaginable’ certainly help to provide the backstory that Talalay sets out for Freddy but they have unfortunately dated badly following the use of early CGI. While inventive, the kills are not as effective as others in the franchise which is owed to the cartoonish and playful nature of the film. The death of Carlos however, is one exception as it embraces horror over comedy and is amongst the most memorable scenes. What’s more, whilst being intermixed with the surrealism of a dream, the horror is based around Carlos having to wear a hearing aid and therefore it is situated in the realm of the real. When Carlos falls asleep, we can hear Tracy shouting for him in the real world. However, in his dream world he is unable to hear her and instead he calls out for Tracy. Unexpectedly he comes face to face with his mother who soon morphs into Freddy, standing before him holding a giant cotton bud. Freddy pushes the bud through Carlos’s head and cuts off one of his ears before throwing him into the boiler room we recognise as Freddy’s lair. Without the use of his hearing aid, Carlos is left to stagger amongst the pipes unaware of Freddy’s location. Here, the sound design ramps up the tension and horror as we can only hear what Carlos can; the sound of his own heartbeat and heavy breathing while Freddy moves about in all directions, taunting him.

The suspense which is so successfully created here is broken by another cartoonish insertion when Freddy pulls out a blackboard. Caressing the board with his knifed fingers, we are encouraged to be both horrified at the thought and amused at Freddy’s antics. However, while the self-reflexive, poppy tone of the film makes it rich in terms of exploration and analysis, here its propensity to always lean into comedy means that the magic of the horrific moment is sacrificed.

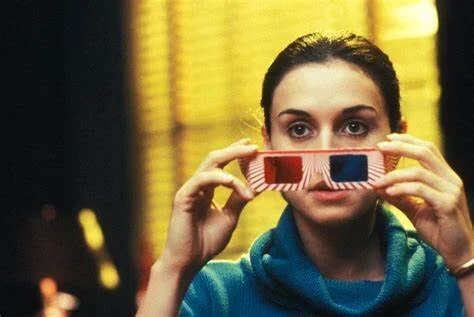

Freddy’s Dead also tried to cash in on the 3D craze but to limited effect as the 3D only came into play in the climatic scene when Maggie goes into her dream to fight Freddy in the final showdown. A plan to bring Freddy out of the dream is laid by the Doc and followed by the most indiscrete plug ever. Maggie must put on the glasses here (as do a now confused audience who have been sitting in 3D glasses for the duration so far) as although they mean nothing in the real world, in the dream world they will allow you to create anything you want. While other attempts to give the film a cool edge might have been successful, the addition of 3D feels like a hammy afterthought.

The little girl motif used throughout the film is moderately successful when played by a child actress (Cassandra Rachel Friel). However, when in the final act of the film an adult Maggie dons the dress and wears pigtails with ribbons in her hair, this feels jarring. While the intention behind putting her in this costume may have been for it to act as a symbolism of how ‘little’ she feels inside and her regressive state in this scene, the overall effect leans more towards the ridiculous and fanciful than the serious.

The final showdown also feels more vaudeville than horror as knives, punches and explosives are thrown amongst a backdrop of pandemonium and chaos that lacks structure and suspense. All this might just be worth the wait though for the triumphant moment when Maggie not only seizes the glove but puts it on her own hand, a symbol of her reassertion of power and control. In a fitting concept for his demise and finale, Freddy is butchered in the stomach with his own knife-encrusted glove by his own daughter. This sounds good in theory, but the reality is strange and unexplainably underwhelming. An explosive is lit and thrown towards Freddy but not before he has the chance to utter a final, campy, self-aware quip: ‘kids.’

As many women in horror have done before her, Maggie laughs in her final moments and as she delivers the words: ‘Freddy’s dead’. There is no sense of conviction or certainty in her voice however, suggesting that the director, the actor, the writer and even the audience may all share a collective awareness that killing Freddy is an impossibility. As the credits roll, Talalay cannot resist a ‘best-of’ clip reel showing images from films across the series, another distinct reminder that while this film is its own entity it will also never escape association from the franchise as a whole. As part of the film’s marketing strategy, the press team arranged for a full funeral service to be held for Freddy complete with coffin, sweater, glove and the cast from the franchise. We know now of course that this wasn’t the last of Freddy but if we listen carefully to the lyrics of the final line of the final song Why Was I Born? (Freddy’s Dead ) by Iggy Pop there was never a suggestion that Freddy would remain forever dormant: ‘do you really think that Freddy’s dead?’’

What Talalay provides in Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare is a film that is rich in terms of critical analysis, especially having had 30 years to breathe. It’s self-awareness, engagement with pop-culture and with the franchise as a whole all point to an aim to create a work that seeks to both acknowledge and subvert our expectations. However, in measuring its success as a horror film it is (unfortunately) mostly ineffective. Even Talalay herself admits in the documentary Never Sleep Again that in retrospect she would have ‘gone harder on the horror’. After five films in the Elm Street franchise, and with interest in slashers dwindling it was clear that fans were pushing for a new kind of horror. As a result, the genre had to change, to evolve and recognising this, Talalay took some bold chances in order to reimagine and update Freddy for the early nineties.

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

Possessor is a slick futuristic thriller in which Tasya Vos, an assassin for hire, must manage her responsibilities as an elite killing machine and complex feelings towards her husband and son, whilst taking on another high-profile job that will push her to the edge of her sanity.