[Editorial] A New Wave of Horror Stories in Pop Music - Part 1

As an increasing number of streaming services fight for audience attention, the pop music landscape has become increasingly aestheticized and willing to indulge in its own worldbuilding. The Weeknd famously attended award shows in costume—fake blood and all—as the protagonist from the music videos corresponding with the release of his album After Hours (itself titled after the 1985 Martin Scorsese film of the same name), a concept album revolving a strained love and an escape to Las Vegas that presumably comes equipped with a metric ton of cocaine.

So too has pop princess Olivia Rodrigo, who dedicated her VMA Best New Artist award to “girls who write songs in their bedrooms,” utilized beloved references to bring life to her lovelorn teenage breakup album SOUR. Throughout her debut album, Rodrigo repeatedly pays homage to her idol Taylor Swift, another former teen whisperer, in her songwriting. She has also starred in music videos that round out her scrapbook of romanticized adolescence by incorporating imagery from films like Carrie (1976) and The Princess Diaries (2001). Even Doja Cat has taken her off-kilter, memetic impulses to new cinematic heights, creating a fictional universe in her music videos for her most recent album Planet Her, all of which depict extraterrestrials of some sort that inhabit the album’s titular planet and its worship of feminine sexuality. This extension of musical ambition has gained even more depth as artists have increasingly begun to regard audiovisual projects as less of a promotional feature and more of an artistic endeavor in of itself. 2021 alone has seen the release of feature films from Halsey and Kacey Musgraves to accompany their albums If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power and star-crossed, respectively, which have both acquired exclusive releases on streaming services.

Neither music videos nor concept albums are unique to the Internet age. Both of these formats have existed for decades: concept albums initially picked up popularity in the 60s and gained near ubiquity in the 70s, and the concept of the music video as we know it was introduced in the same decade before gaining network regularity in the 80s with the advent of MTV. Yet with the proliferation of specific aesthetics warped and reupholstered as collage on online social networks, both of these formats have taken on a new identity, as a more fractured network of promotion in the music industry has required more novel approaches.

Less discussed is the topic of a burgeoning subcategory of conceptual projects that glean direct inspiration from pre-existing films. Many albums comprise this description in a broad sense. Ironically, for as much as Olivia Rodrigo’s debut album serves as a reflection of the teen tales that accompanied her coming of age, one of many artists whose discography Rodrigo was accused of plagiarizing by her detractors wears her cinematic influences even more blatantly. Mia Berrin, frontwoman of the group Pom Pom Squad, including a track called “Lux” named after the foremost character in Sofia Coppola’s 1999 film The Virgin Suicides on the band’s debut album Death of a Cheerleader. Despite these various influences, one genre of film in particular has provided considerable inspiration to pop songwriters as of late: horror.

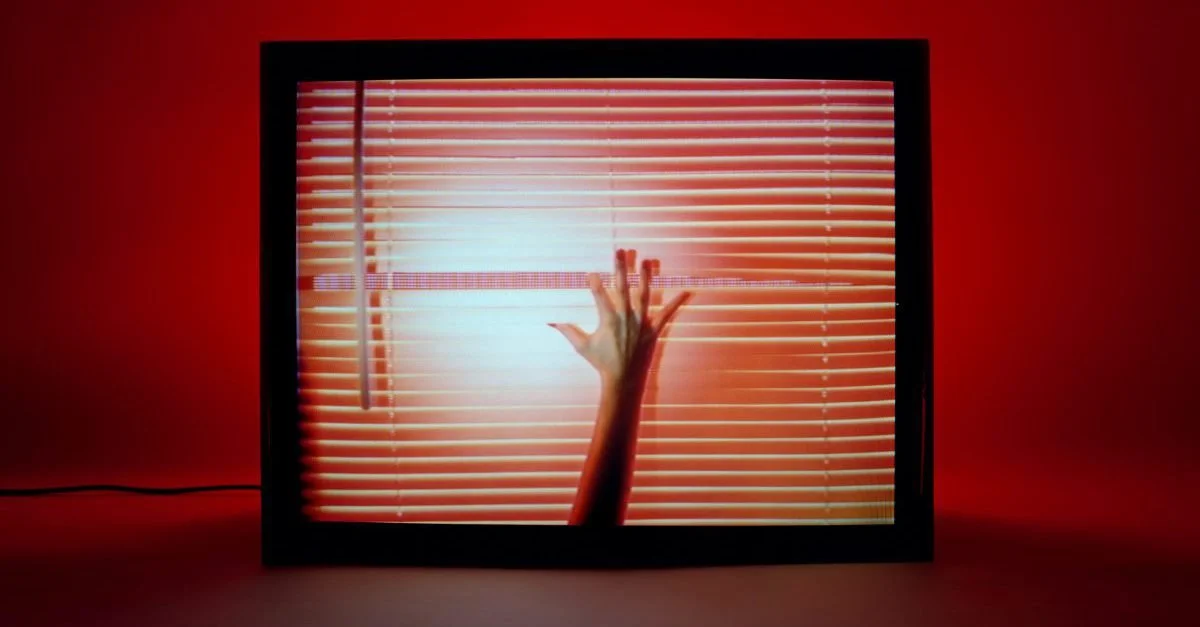

Perhaps the most obvious example of this trend comes with the most recent CHVRCHES album, its title Screen Violence an apt reflection of the project’s haunted content. The album’s aesthetic makes it no secret that its roots lie in horror: the cover displays a disembodied hand rising from a strand of blinds and out of a TV screen, all of which is bathed in the glow of neon red light. This motif of ominous, lurking shadows clawing their way through digital boundaries echoes throughout the project, lead vocalist Lauren Mayberry’s voice being filtered through glitching effects and fractured vocoders against an uncharacteristically murky, genre-bending instrumental palette, a departure from the crisp, frenetic synth work that broke the trio in their earlier years.

That increased paranoia is fueled by a deeper artistic urge than mere homage, though, as across Screen Violence, Mayberry’s lyrics divulge the harrowing truth in moving forward in the wake of a relationship that enacted lasting damage on her psyche. The album’s music videos invoke frequent images of revolving doors, developing photographs, and static-laden digital duplicates of Mayberry’s figure. All of these symbols, with their splashy, colorful but cryptic imagery are not only clear signs of their influences from horror directors like John Carpenter and David Cronenberg, but, even more visibly, are adequate reflections of Mayberry’s struggles to find a sense of personhood after having been tethered to someone who made her question if she even had a sense of identity.

The opening track “Asking for a Friend” pleads for a potential opportunity to move forward with this person, but the immediate successor in the album’s tracklist, “He Said She Said,” wastes no time in expressing the anger underlying Mayberry’s processing of guilt for her own conception of self, recounting such discussions as, “He said, ‘You bore me to death’ / ‘I know you heard me the first time’ / and ‘Be sad, but don't be depressed’ / Just think it over, over.” In a revelation of how much the memories, and her difficulty in even retrieving them, pain her to revisit, the most emotional moments of the song are the most distorted, the choral refrain of “I feel like I’m losing my mind” repeating, glitching and shifting across pitches, thrashing about the mix in a way that Mayberry herself knows she can’t replicate for fear of embodying the supposedly unflattering behavior this partner so cruelly reprimanded.

Though the horror that characterizes this project is ostensibly the manipulation Mayberry faced at the hands of her ex, she makes it clear that the real terror in such a dynamic is its aftermath. Her literacy within the horror genre is expressed most explicitly in the track “Final Girl,” an investigation of the titular archetype that cautions, “In the final cut / In the final scene / There's a final girl / And you know that she should be screaming.” That the most gruesome effects of the horror genre, the trauma that most survivors will inevitably have to face after the credits roll, is left implied in a fictional scenario that Mayberry now embodies in real life, a recognition that those who identify with her in relation to a male antagonist would likely find her less compelling in a journey that involves independently divesting from such a journey.

The path is even at times suicidal: “How Not to Drown,” a collaboration with goth rock stalwart Robert Smith, introduces itself with the lines, “I'm writin' a book on how to stay conscious when you drown / And if the words float up to the surface, I'll keep 'em down,”. Mayberry’s admission that she represses her most raw emotions, even in the face of vulnerability, understands that, as a woman, she is made constantly hyper-aware of how receptive she is viewed to be by others, even in the midst of coming to understanding the hurt that has been afforded to her. For CHVRCHES, the most visceral horror is one of reconciliation, and with that comes the constant vigilance that experiencing such a hardship as a woman necessitates to prevent further damage. By the end of Screen Violence, the album’s arc does not reach a strict resolution, concluding not on a note of a fixed point of healing, but on an instance of Mayberry’s active rejection of this former partner’s advances, now having found some semblance of strength to do so.

A similar theme arises in Billie Eilish’s debut album, When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? Unlike CHVRCHES, Eilish already had a robust American fanbase prior to even releasing the album in full, with some of her older singles like “ocean eyes” charting during the leadup to her album’s release. Most listeners are likely familiar with the unsettling undertones of Eilish’s first full-length project—not only did “bad guy” skyrocket to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 upon the album’s release, ending the year positioned at #4 on the year-end singles chart (and keep in mind, this was the year Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” bulldozed everything in its path to break the record for the single with the most amount of weeks at #1), but other songs such as “bury a friend” and “when the party’s over” also found noteworthy chart success. Yet in spite of the tremendous popularity of her hits, the true depths of her debut as a project in its entirety are likely lost in a context that is only informed by its imposing singles, rather than the angst-ridden tenderness at the album’s center.

Though “bad guy,” the first real song on the album, displays Eilish toying with the idea of power in a playfully whispered delivery accompanied by a tight bass line, prodding a prospective love interest with questions of their masculinity with the implication that they don’t stand a chance against her more reserved means of control, her façade proves to be exactly that upon further listening to the album in full. Immediately after, the song “xanny” narrates her downbeat revulsion towards her friends self-medicating and falling out of touch, even if the underlying fear is that she’ll fall into the same behaviors, her emotions later displayed on the album at times prompting her to desire the same escapism. The first half of When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? further exercises her projections of control, with “you should see me in a crown” declaring “I’m gonna run this nothing town / Watch me knock ‘em out one by, one by one” as a means of deflecting potential romantic prospects’ interests and transforming them into an outlet for her to express domination for herself.

The album’s breaking point, however, comes with “when the party’s over.” At first, the song presents itself as a somber piano ballad, but as the verses progress, the synth bass starts to rumble at a louder volume, rupturing at a break in the second verse that interjects a distorted voice instructing, “call me back,” before she returns to her poised, mournful lilts into falsetto to grieve the fact that her narrative love interest has abandoned her in the wake of her repeatedly expressing unrequited love. The mirror has cracked, Eilish no longer able to think of herself as a bruising foe.

After this moment, the album more explicitly confronts her own fears, with even the most frightening track, “bury a friend,” now posing questions of her ability to be sought out by others, asking, “Why aren’t you scared of me? / Why do you care for me? / When we all fall asleep / where do we go?” Eilish herself has posed an interpretation of the song as a confrontation with a monster under her bed, but in the context of the album, that monster’s capacity for damage grows increasingly emotionally intertwined with the terror such an unexpected presence could cause. Such a monster could easily be one of the friends or potential lovers that break Eilish’s heart throughout the course of the album.

The album ends with “i love you,” easily the most ethereal of any track on the project. Even its compositional sense of peace is constantly forced to grapple with an undercurrent of anxiety, however, as Eilish narrates the sudden fear she faces when a friend uses the titular phrase to describe their affection for her. The ballad is muted, taking time to delicately arrive at its climax with a runtime of nearly five minutes, but even with that softness, Eilish sings her lyrics of conflicted overwhelm with an agony that is expressed deeply in her chest. At this point in the album, the change she describes in relationship dynamics is still not one for which she is fully equipped, but one she can now face with an honest understanding of her own emotions, and evolution from the album’s beginning of using ironic posturing to deflect from the truth of her vulnerability.

Eilish named the 2014 horror film The Babadook, its titular source of fear also being an imaginary friend, as her greatest inspiration for creating the project, a fitting reference point. The horror present in When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? is one that is illustrated on the album’s cover: lurking in the shadows, always present but never fully visible, encroaching with such an intangibility that makes its capacity for causing inner turmoil that much more terrifying. The album is an encounter with the unconscious, and a reckoning with how to contextualize such deeply-rooted emotions now that they have been uncovered. Even Eilish’s style of dress during this album cycle reflects this anxiety; though her choice to clothe herself in heavy, oversized pieces was primarily a decision made to discourage onlookers from making inappropriate comments about the body of a teenager, such a willingness to deflect attention away from her figure by adding layers to make it indistinguishable perfectly parallels her impulse to do the very same in the relationships she navigates within the narratives of her debut album.

Eilish’s age during the creation and promotion of When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? is also central to the album’s thesis. More than having a sense of ironic humor representative of the young generation in which she came of age, the understanding that she must find a way to honestly navigate her emotions, however unflattering others may find them, in order to sustain her own capacity to care for others is a terrifying reality to grasp as a teenager, particularly a teenage girl. That Eilish recognizes such stakes and possesses the language to describe these experiences in detail is in of itself a site of horror, but one she must manage if she wants to survive.

Conversely, Kim Petras takes a vastly different approach to relationship dynamics in her horror-influenced output, Turn Off the Light, which began as the mixtape Turn Off the Light, Vol. 1 in 2018 and was repackaged in 2019 with a similar number of new songs. Of all the pop projects that have taken influence from horror tropes, this album is easily the most transparently “novel” in its approach; Kim Petras herself has admitted that her main goal with the album was to provide a Halloween counterpart to the oversaturated landscape of redundant Christmas tunes (one track, “Massacre,” even interpolates the melody of “Carol of the Bells” in its verses). Many of the project’s songs are crafted for isolated incidences of pop disposability—a great hook, an invigorating groove, etcetera—rather than a coherent arc spanning across the entire project, as evidenced by the album’s ever-increasing tracklist and life span.

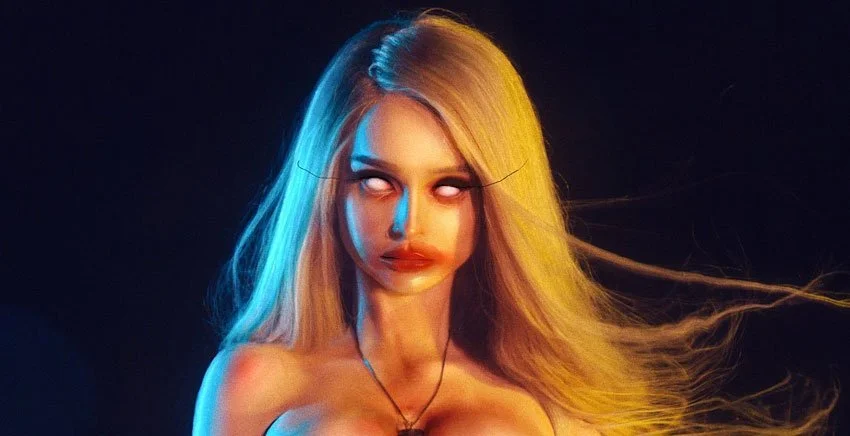

This approach is aided by Petras’ intentionally hyper-feminine persona, one that has permitted her to be literally cast as a modern princess in multiple music videos and still maintain a degree of sincerity. With her blonde hair, penchant for pink, and lyrics of romantic melodrama, Petras embellishes a particularly coy display of aesthetics associated with womanhood, likely a deliberate exaggeration, given her experience as a trans woman since her preteen years. Her outsized embrace of pastel-colored femme fatale ideals is given a darker spin in her Turn Off the Light series; her signature “woo-ah!” vocal tag is now howled and distorted. Even the lone guest appearance on the album is credited to Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, the television personality whose mix of supposed vapidity and B-flick horror literacy makes a perfect match for Petras in a spoken word interlude during the album’s title track. By necessity, Turn Off the Light cannot take itself too seriously, as such a tone would compromise Petras’ artistic image, but the album is made more functional because of this, and arguably more interesting as a result.

The tracklist of the album version of Turn Off the Light alternates between one fully-formed song and an instrumental, house-infused interlude. Each song operates on a loose formula of taking a vague horror conceit and using it as a metaphor for display of sexual prowess or romantic despair. “Close Your Eyes,” the inaugural track on the first edition of Turn Off the Light, was the catalyst for transforming her concept into a fully-formed release, and its imagery feels the most dimensional as a result. In the song, Petras narrates from the perspective of a sexual domination, using lycanthropy as her metaphor of choice; her “designer taste” that is mentioned in the first verse morphs into an all-consuming, inescapable thirst by the song’s chorus that even her prospective lover can’t avoid. Similarly, “There Will Be Blood” advises a partner to run for their life as Petras belts out their impending doom as they sexually submit to her, and “Wrong Turn” suggests a double meaning in being made vulnerable by falling for “the wrong one on the wrong night,” as the chorus describes, and being subjected to Petras’ slasher-themed urge to remain the last one standing.

Doom is not the only fate that greets Petras’ lovers in Turn Off the Light: the title track simply requests that her partner perform the titular action in order to “do it right,” or experience a most profound display of sexual pleasure, enhanced by the uncertainty of what will come next. Neither are her lovers the only victims of the horror she promises. Near the end of the album, Petras begins to direct her focus inward, examining her own reputation as a merciless inhabitant of sexual power in the track “In the Next Life,” it’s verses full of occult juxtapositions along the lines of, “I'm the greatest God created / I'm a sickness, I'm contagious / I'm a demon, power trippin' / on a mission, and vindictive.”

That even she is conflicted on her status as a villain throughout the album’s progression complicates the narrative as a pure empowerment fantasy. Even she seems to recoil from the true nature of her actions in the album’s most gruesome assertions of dominance; in “Close Your Eyes,” she asks her lover to direct their attention away from the fear that her domination might evoke, commanding in the chorus, “Don’t try to fight it / Just close your eyes.” Perhaps the freedom to fully embody a dominatrix persona terrifies Petras as much as it does her own “victims” when considering its consequences—as a woman, exercising that control, particularly in a sexual space, always presents a sacrifice of full safety.

Though Petras has not spoken much about the political implications of her trans identity outside the context of performing at Pride celebrations, she has admitted to initially feeling ashamed of her gender as a teenager that she has now come to embrace. That willingness to grapple with the fullness of her identity, as well as what it means to proudly exude such a confidence in it, becomes the album’s most prominent theme, and given that the album has no corresponding music videos or promotion for any specific singles, this exploration is clearly a passion project for Petras. What would otherwise be a standard collection of synthpop tunes is made more complex because of this.

That exploration of the dynamics of power as a trans woman is even further complicated by the grim irony of the fact that Lukasz Gottwald—known more prominently by his production nom de plume, Dr. Luke—has a co-writing credit on every song from the album, including all of the instrumental tracks. Though Dr. Luke was a prominent pop producer during the turn of the decade into the 2010s, and has still worked with acts like Doja Cat to produce the hit song “Say So” under the pseudonym Tyson Trax, his name has now become synonymous with the allegations of sexual assault and emotional degradation that his frequent collaborator Kesha leveled against him in 2014, as well as the subsequent distancing many of his former colleagues made from him as expression of solidarity with her lawsuit against him and his record label. While Petras has mostly kept quiet about this decision to collaborate with someone with such severe allegations to his name, what she has claimed in defense of her decision to work with him has negated and downplayed in the vaguest possible terms the experiences Kesha detailed in her lawsuit.

This tension is her ostensible artistic aims and her execution of such ambition makes sense in the context of Turn Off the Light. While the album’s thematic reckoning with the idea of sexual control and agency is fun to parse, that it is explained in vague, campy metaphors rather than explicit introspection allows Petras to have her cake and eat it too. While the instances of introspection that occasionally appear on the album allow her to exercise the idea of contemplating more serious material, the lightweight stakes of the album do not require her to actually take that step forward and fully deconstruct her image as a pop star. If anything, within a context outside of her work, embodying power at the cost of others’ subjugation is not a fantasy for Petras—by collaborating with a man who has been outed as abusive on such a regular basis, she makes the narrative real in the production of her own art.

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667061747115-NTIJ7V5H2ULIEIF32GD0/Image+1+%285%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

When people think of horror films, slashers are often the first thing that comes to mind. The sub-genres also spawned a wealth of horror icons: Freddy, Jason, Michael, Chucky - characters so recognisable we’re on first name terms with them. In many ways the slasher distills the genre down to some of its fundamental parts - fear, violence and murder.