[Editorial] Alex Forrest Read Too Many 80s Fashion Magazines

Alex Forrest, played by Glenn Close in British director Adrian Lyne’s 1987 film Fatal Attraction, is one of the most famous female villains in movie history. Thirty-four years after she entered eternal life via cinema, she is still a catchphrase (“I’m not gonna be ignored!”) and the subject of a popular slang term for a violent romantic stalker (“bunny boiler”). Thanks in large part to Close’s brilliantly unhinged but oddly sympathetic portrayal, Fatal Attraction became a decade-defining film, as much a synecdoche of the 80s as Princess Diana, aerobics classes, and Chardonnay wine coolers.

Fatal Attraction is a tremendously good film, but not a great one. It isn’t even a new idea. Sixteen years before its debut, a thriller with a very similar plot was released, titled Play Misty For Me (1971). Noteworthy for marking Clint Eastwood’s directorial debut, Misty stars the late Jessica Walter as Evelyn Draper, an obsessed fan of Eastwood’s Dave Garner, a radio DJ who spins jazz tunes and reads poetry over the airwaves. Like Alex, Evelyn pretends to be looking for no-strings-attached casual sex, and seduces Garver into a one-night stand, only to reveal later that she wants a permanent romantic relationship. Like Alex, she attempts suicide by slashing her wrists in order to emotionally blackmail the object of her obsession. And again, like Alex, Evelyn turns violent when Garver rejects her and goes after her rival for his affections — an ex-girlfriend named Tobie, played by Donna Mills.

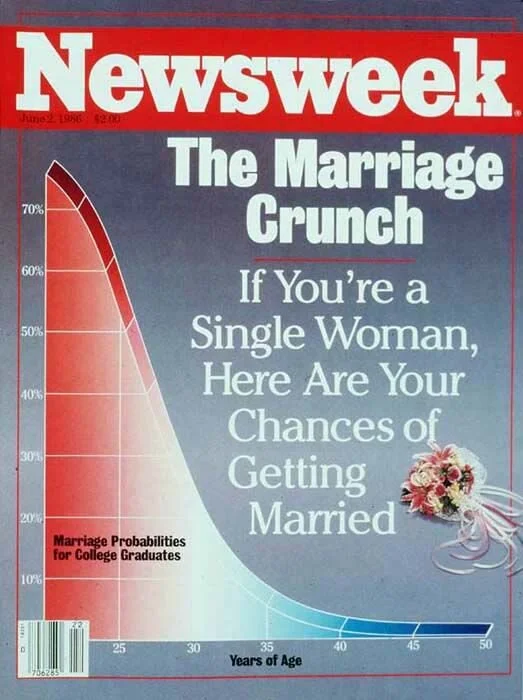

Misty was a critical and commercial hit for Eastwood, but it didn’t have the huge pop culture impact that its successor had a decade-and-a-half later. Fatal Attraction managed to capture the public’s attention because its themes touched on numerous trends/events that were bedeviling audiences of its era. One was the third wave of feminism, in which working women made clear their determination to break the corporate glass ceiling. Another was the then-new AIDS crisis, which reflects the film’s theme that sex with strangers is deadly. Also on trend was the infamous, so-called “Newsweek study” — a flawed 1986 report on the marriage prospects of contemporary women, which notoriously claimed that a 40-year-old, never-married woman had more of a chance of being killed in a terrorist attack than finding a life partner. (Significantly, the childless, never-married Alex is 36.)

Glossy, relentless, and unrealistic.

These themes dominated the glossy fashion magazines of the times, like Glamour, Mademoiselle, and Cosmopolitan.This type of publication was often toxic to female self-esteem in the 80s.They promoted impossible beauty standards and carried relentless articles about climbing the corporate ladder while looking terrific and landing Mr. Right. A particularly obnoxious trend was addressing the reader with comments like “have your secretary make arrangements for a power lunch” — completely oblivious to the fact that most of their 20- and 30-something readers were more likely to be a secretary than an executive. The tone was not only unrealistic, but deeply demoralizing: “What? You are 27 and you don’t have a corner office yet? What’s wrong with you?”

There was no room in these glossy, breathless pages for a young woman who was happy with an average job and marriage to the boy next door. No, after achieving the high-powered career with the corner office, the modern 80s woman needed a high-powered alpha man to go with it— a handsome, financially successful man like Dan Gallagher (Michael Douglas), the corporate lawyer who becomes the object of Alex’s twisted affection.

On the surface, Alex is the ideal 80s Cosmo Girl or Glamour Woman. She has the fancy job, the trendy wardrobe, the fabulous flat, the sexy, toned bod. All she needs is a suitable Mr. Right to help fill out the set. She never really loves Dan Gallagher; he’s just the next-to-last checkbox on her to-do-list (the perfect, designer baby being the final one.) Unfortunately, it doesn’t happen the way Alex envisions it, and she reacts with all the rage and fury of a disturbed woman who read 80s fashion magazines and took them all too seriously. Life, as John Lennon once said, is what happens to you when you are making other plans— and if you were a young career woman in the 80s, Newsweek was there to remind you of that evident fact.

Alex, of course, has many character flaws, but what comes through most clearly is her inflated sense of entitlement. She is entitled to finish her checklist, dammit! Note that when Alex tries to kill Dan’s stay-at-home wife, Beth, she repeatedly calls her rival “selfish” for not wanting to step aside and let Alex have her husband. When Beth shoots and kills Alex in self-defense, one may wonder if Alex’s last thought was that it was all a terrible mistake; the fashion magazines told her she was supposed to “win,” not the frumpy housewife.

Seventies vs. Eighties

Contrast Alex’s lifestyle with that of Play Misty For Me’s poor, mad, Evelyn Draper to see how different women’s onscreen lives were only 16 years later. Unlike Alex with her briefcase and checklist, Evelyn’s only ambition is to become Mrs. Dave Garver. Instead of raging “I’m not gonna be ignored!”, she pathetically cries, “I love you, I love you!” while clutching at Dave with her bandaged arms. She doesn’t even have a job — her source of income is a mystery. Audiences of the 70s didn’t react to Evelyn the same way later audiences reacted to Alex. That may be because the way she was depicted — clinging, man-hungry, hysterical — was not at all that different from the way a lot of women were depicted on early 70s television and movie screens. Audiences thought, “Oh, poor Evelyn, just another shrieking woman who can’t get a man!” They felt sorry for her, as if she were a female equivalent of Norman Bates.

Not used to seeing a smart, independent, otherwise empowered woman going apeshit over an unrequited love, the 80s audiences were a different matter. They hated Alex Forrest. When I saw Fatal Attraction in its first release on the big screen, the full theatre clapped loudly at Alex’s death scene. Even my date at the time clapped, which possibly was a clue that our relationship wouldn’t work out (Dear Reader, it didn’t.) In fact, Evelyn is far more lethal than Alex; she has a body count. Alex, in contrast, causes no one’s death but her own.

Yet, Alex is the more hated character. As an apt illustration of how much audiences despised her, film execs changed the original ending to accommodate a test audience’s very negative reaction. This alternate ending can be seen on YouTube. It depicts Alex slashing her throat with a butcher knife that has Dan’s incriminating fingerprints on it. Glenn Close (1) herself thought Alex was a tragic case and preferred the original ending. The test audience, however, wanted bloody revenge at this uppity interloper who dared to disrupt a happy nuclear family. As it turns out, the perfect family was not so happy after all. This is evident through the question Alex puts to Dan about why he cheated on Beth if he loves her so much; a question which Dan fails to provide an answer to.

Unlike my date at the time, I didn’t clap when I first watched Alex’s death scene. I thought it was heartbreaking. Who hasn’t felt rage and grief because of an unrequited love at some point? I’d been there myself, not too long before I saw the film. But most of us eventually pick up our toys and go elsewhere. Alex Forrest probably would have had a happier fate if she’d just married the boy next door and chose a subscription to National Geographic instead of Cosmo.

Sidebar:

Fatal Attraction: A Man Bites Dog Story

One of the great ironies of Fatal Attraction is that in real life, it is men who are most likely to be violent stalkers and women who are most likely to be their victims. Female-on-male stalkers are not unknown, but they are not nearly as common as the reverse.

In the US (2), roughly three times as many women as men report being victimized by stalkers. In the 1980s, the decade that Fatal Attraction owned, three particularly gruesome stalker attacks gained worldwide attention, all involving young female actors in their 20s. These were Rebecca Schaeffer, the 21-year-old star of a television sitcom called My Sister Sam; Theresa Saldana, 27, most famous for acting in Martin Scorcese’s landmark Raging Bull; and Dominique Dunne, 22, who played the teenage daughter in Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist. Of the three, only Saldana survived her attack, although with serious injuries that maimed her for life. She and Schaeffer were both set upon by obsessive male fans, who used private detectives to help track down the women’s personal residences. Dunne, on the other hand, was stalked and stabbed to death by a jealous former romantic partner. A less famous case involved Marla Hanson, a New York photographer’s model, whose face was viciously slashed by two men hired by a would-be suitor angry at Hanson’s rejection of him.

Sources:

1) https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/03/glenn-close-fatal-attraction-ending

2) https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_Stalking_508_QC_v2.pdf

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Getting sticky, slimy & sexy with body horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689072388373-T4UTVPVEEOM8A2PQBXHY/Society-web.jpeg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Editorial] They’re Coming to Re-Invent You, Barbara! Night of the Living Dead 1968 vs Night of the Living Dead 1990](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687199945212-BYWYXNBSH00C4V3UIOFQ/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+19.05.59.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Short & Feature Horror Film Double Bills](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687770541477-2A8J2Q1DI95G8DYC1XLE/maxresdefault.jpeg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667061747115-NTIJ7V5H2ULIEIF32GD0/Image+1+%285%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

I can sometimes go months without having a panic attack. Unfortunately, this means that when they do happen, they often feel like they come out of nowhere. They can come on so fast and hard it’s like being hit by a bus, my breath escapes my body, and I can’t get it back.