[Editorial] Christine: 1958 Ford Fury or a Symbol of the Teenage Outcast?

John Carpenter’s Christine (1983) tells of the events which unfold when an unpopular nerd Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon) buys a car called Christine which he quickly becomes obsessed with. It is implied that Christine is inherently evil, killing anyone that gets in the way of her and Arnie. Just by the simple act of naming her Christine, the car becomes personified, gendered, and therefore humanised. She is not just a materialised object but becomes her own character.

When asking people what they think of the film Christine, fans almost instinctively recall the image of her red paint engulfed in flames:

This scene—captivating and disturbing—represents the destruction of both the film’s protagonist and its supposed antagonist. Although on the surface Christine seems to be about a car that is evil, could the vehicle also symbolise the teenage delinquency of the 1980s? Christine is a product of the society it was produced within and one in which teenage behaviour was seen as a cause for moral panic. Right-wing conservatives held ambivalent attitudes towards teenagers of the 80s often linking them to a rise in drug taking, renewed love of rock n roll and rising AIDS and HIV rates. Carpenter imbues Christine with many of the same vices as the 80s teenage delinquent, that American society actively categorised. Teenagers were not properly understood, adults could no longer relate to this new generation of outsiders and rebels, just like Christine is alienated as an outsider.

Outsiders in society

Mary Findley claims in Stephen King’s Vintage Ghost-Cars: A Modern Haunting, that Christine functions temporally and narratively as a ghost – an entity from the past (the 1950s) that has returned to haunt Arnie’s world in the present (the 1970s). This naturally renders Christine“other”: as a creature from a bygone time, she is presented as unnatural and unrecognisable to characters in the film. In this respect, Christine is comparable to the teenage condition: being necessarily and naturally liminal, on the brink of adulthood, and characterised by experimentation and revolution. The teenagers of 1980s America were particularly novel and unrecognisable to the older generation of Americans because of their new-found greaser sub-cultures, anti-establishment attitudes, and a renewed love of rock’n’roll music. In Linda Williams’ essay When the Woman Looks, she argues that in horror films, women identify with monsters because they recognise the same ‘otherness’ within themselves. Christine’s trajectory mirrors this identification of otherness, because the figure of the teenager can also be linked to liminality: not quite a child but not quite an adult, a figure on the borders. Arnie is perhaps attracted to Christine because he witnesses the same liminality in her as an obsolete artefact that society sees in him as a teenager. In Arnie’s empathy, Christine and Arnie become one and the same – two figures on the margins of American society.

The Frontier of Freedom

Christine enacts what a rebellious teenager craves: the frontier experience away from the parents’ home. In The Uses of Enchantment, psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim states that ‘to those who are on the borders of adulthood and adolescence, the world beyond the home and duty becomes attractive’. However, after this initial infatuation with the world beyond the home, destructive encounters may occur. Arnie craves the world beyond the home, and Christine can transport him there. But the Plymouth Fury ’58 herself also becomes Arnie’s whole world outside of the home. This sadly ends in his death inside of the car that he was so besotted with.

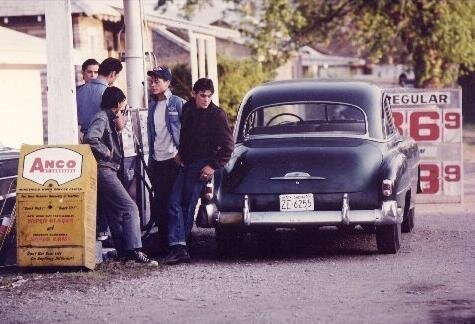

Christine also provides something that Arnie craves: an exclusively male space. This trope permeates other films that depict teenage delinquents. For example, in The Outsiders (1983) Sodapop Curtis is seen working in the all-male environment of the gas station, surrounded with masculine ‘banter’ which epitomises what a contemporary audience would coin as ‘ toxic masculinity’.

The depiction of male friendships and masculinity itself seems to flourish in the realms of the car, particularly in films that involve adolescent boys exploring their newfound freedom that cars bring to them. It is in the car that Dennis tells Arnie that he needs to “get laid” as well as commenting on someone as a “walking sperm bank”, implying that a form of toxic masculinity can flourish in the confines of the car, that audiences otherwise do not witness in the domestic sphere. The car, then, represents a space craved by the teenage outsider, as it is somewhere where they can be understood, without judgement, surrounded by other male friends.

Transformation

In the film, Christine undergoes a physical transformation which parallels the transformation of Arnie’s personality. When Arnie first purchases Christine, she is old, rusty, and unattractive, but transitions into something beautiful, shiny, and new, as she has the power to regenerate at will. Equally, at the start of the film, Arnie is presented as unattractive, nerdy, and awkward. However, when Arnie starts investing himself into Christine, as Phillip Simpson observes in Stephen King’s Critical Reception, ‘he sheds his eyeglasses, dresses sharper, seemingly becomes more confident, and gains a girlfriend.’ Arnie’s clothes and hair are radically transformed into something that more closely typifies his car – the teenage delinquent.

Arnie’s character might be not just an abstract social commentary, but perhaps based on a real-life teenage delinquent: James Dean. The image of Arnie in fig. 3 is like James Dean’s Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause (1955): both share the same greaser ‘bad boy’ style, and whilst Arnie sits in his red car of Fury, a red car can be seen behind Stark in Rebel.

Dean himself personified the idea of the teenage rebel which was mainly shown through his greaser style and care-free attitude. Findley notes that Dean longed to find a place in the world – just as Arnie craved a frontier experience away from home – so when [Dean] ‘purchased a 1955 silver Porsche Spyder – a racing car – the power and masculinity of Dean’s image was magnified.’ Dean became a popular culture sensation, now immortalised in popular media alongside the image of his car. However, it was within Dean’s car that he became not only empowered, but also a figure of both delinquency and masculinity yet it was his car that led to his untimely death. Just like Arnie – as he transitions into this stereotype of masculinity that parallels Dean’s 1950s figure, he simultaneously deteriorates into a delinquent and becomes marginalised. Christine – a ghost – a car from the past, haunting Arnie’s present, and Arnie- a James Dean-like figure of the 50s, that possesses Christine: both become threatening, menacing presences within their environments as the film progresses. The car and the teenager become one and the same.

Conclusion:

Christine is a cleverly constructed automobile horror film underpinned by several engaging themes. These themes include masculinity and the love of the automobile, the fetishization of the automobile, and even has hints of the return of the repressed – America’s horrific past haunting the present. But, for the most part, the film’s main themes seem to highlight moral panics surrounding delinquency and teenage culture. In Christine, it is the car that symbolically represents the teenager in their entirety. Christine becomes symbolic for the teenager as her and Arnie have a similar shared experience within American society.

Works cited;

Badley, C. Linda. “Love and Death in the American Car: Stephen King’s Auto-Erotic Horror”, in The Gothic World of Stephen King: Landscape of Nightmares (eds.) Gary Hoppenstand, Ray Broadus Brown (Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1987) pp. 84-93.

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairytales (New York: Penguin, 1976)

Carpenter, John. Christine (1983)

Coppola, Ford Francis. The Outsiders (1983)

Felluga, Dino. “Modules on Freud: On the Unconscious.” Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. [accessed 17/05/2021]

Findley, Mary. “Stephen King’s Vintage Ghost-Cars: A Modern Haunting” in Spectral America: Phantoms and the National Imagination (ed.) Andrew Weinstock (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004) pp. 207-220.

Ray, Nicholas. Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

Simpson, Phillip. “Stephen King’s Critical Reception” in Critical Insights: Stephen King. (Ed.) G. Hoppenstand (CA: Salem Press, 2011) pp. 38-60.

Williams, Linda. ‘When the Woman Looks’, Re-Vision: Essays in Feminist Film Criticism (Los Angeles: University Publications of America, 1984)

‘The Greaser Sub-Culture’. [accessed 26/04/2021]

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] 8 Short & Feature Horror Film Double Bills](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687770541477-2A8J2Q1DI95G8DYC1XLE/maxresdefault.jpeg)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] They’re Coming to Re-Invent You, Barbara! Night of the Living Dead 1968 vs Night of the Living Dead 1990](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687199945212-BYWYXNBSH00C4V3UIOFQ/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+19.05.59.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] The Last House on the Left (2009) with Zoë Rose Smith and Jerry Sampson](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687863043713-54DU6B9RC44T2JTAHCBZ/last+house+on+the+left.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667061747115-NTIJ7V5H2ULIEIF32GD0/Image+1+%285%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

The human body is a thing of wonder and amazement–the way it heals itself, regenerates certain parts and can withstand pain and suffering to extreme extents. But the human body can also be a thing of disgust and revulsion–with repugnant distortions, oozing fluids and rotting viscera.