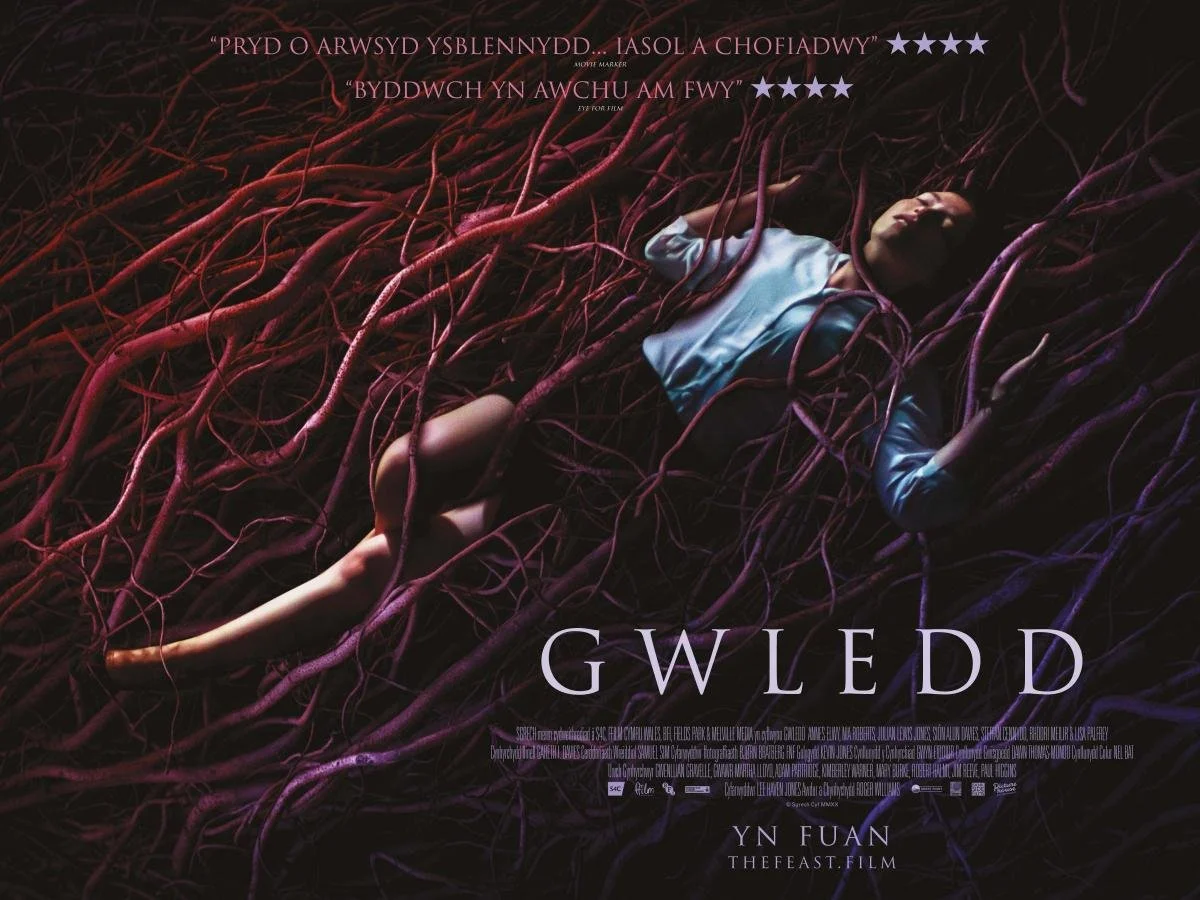

[Film Review] The Feast (Gwledd)

Synopsis: Filmed in Welsh, the picture follows a young woman serving privileged guests at a dinner party in a remote house in rural Wales. The assembled guests do not realize they are about to eat their last supper.

Before launching into this review, it feels important to note that The Feast is the first Welsh-language film to enter cinemas in five years. For context, many Welsh-language productions are also filmed in English, offering a dual option and meaning the Welsh version often ends up buried at the expense of the more easily marketable version. It also represents the first time that accessible Welsh-language closed captioning and audio description will be available on a film. With so few truly Welsh films receiving mainstream attention it is heartening to see accessibility being taken into consideration as part of reaching as many people as possible. That this is a film centering the Welsh-language and political concerns while also being an excellent horror film is incredibly exciting.

Glenda (Nia Roberts) is throwing a dinner party but not everything is going to plan. Between sulky son Guto (Steffan Cennydd) being home against his will, other son Gweirydd’s (Sion Alun Davies) strict diet and the young woman she usually has to help her being unavailable, inexperienced Cadi (Annes Elwy) is sent instead, increasing the pressure on Glenda to deliver a successful evening. As the night unfolds, the strain from family and pressure from outside forces relating to nearby land turns the evening into a nightmare.

The Feast begins with a penetration, focused on the noise and disruption of a drill into the land. The relationship the film has to uncomfortable invasion is set out from the first moments and this continues throughout, building as the carefully stitched, immaculate home gradually comes undone. The house functions as a Grand Designs-style nightmare, a brutal structure in the middle of the countryside that seeks to disrupt the surroundings with a detached kind of opulence. The irony of this is the house, called Life House, is a real house within Radnorshire (that you can book to stay in) designed specifically for reflection and meditation. Indeed, the family at the heart of The Feast find themselves trapped by the house, forced to reflect on their lifestyles. Technology repeatedly disrupts the space, from Guto taking his electric guitar outside into the grass, Gwyn’s (Julian Lewis Jones) gun echoing as he hunts rabbits and even Gweirydd’s state of the art stationary bike that sits outside looking at the vast surroundings, but never exploring them.

Every section of the house is explored, becoming a character in and of itself, punctuated by a reflection room in which rain can pour in through an open roof. While Glenda adores the space, neighbour Mair (Lisa Palfrey) remarks that it looks like a cell, a clear separation between how the pair think about their homes and surroundings. The incredible aesthetic of the home makes it perfect for those long takes and slow shots that dominate the film, with photography that draws the eye. It makes the startling shots all the more startling, with early sound design taking a lead in furthering the clash between the family and the wider space in which they reside. The sleek look of the house is the perfect setting for the gradual ramping of body horror and more fevered third act.

The Feast is, undoubtedly a political film, with Gwyn’s role as an MP only a small part of it. Really, The Feast is interested more in ‘small p’ politics and individual responsibility than the wider political system. Glenda operates not only as the evening’s host within the film, but also hosts us as a viewer, with Nia Roberts’ performance expertly treading the line between drawing anger, but also sympathy. She exists in a space as a former farmer’s daughter with the skills still available to her as almost second nature, along with the skills she has developed in order to fit into her new life. Through her, we explore the difficulty in rationalising those two worlds and it is to Roberts’ credit that she is able to find sympathy in an initially unsympathetic role.

Elsewhere in the cast, Steffan Cennydd is doing great work bringing sullen and troubled Guto to life. As someone from a reasonably rural area myself, his big-city longing for noise and buzz is almost too easy to identify with. Guto is not interested in farming nor the perceived respectability of politics. His desire to leave Wales is tied to a search for further escape that he has found in his drug use - being forced back to the house without access to that freedom or drugs operates as a punishment. Special attention must be drawn to Sion Alun Davies whose performance as the deeply strange, highly charged Gweirydd is one that you are repelled by but which is absolutely perfect in context. Elsewhere, although amounting to a mostly cameo role Rhodri Meilir delivers as Euros, whose presence at the party adds an extra layer of tension. While Glenda makes for a perfect host, it is Annes Elwy’s incredible performance as Cadi that ends up drawing the most viewer empathy, straddling the line between under threat and threatening with precision. That this is done with long periods without any dialogue just furthers what a special performance it is. Initially it would be easy to read the film in terms of its patriarchal influence, with the male characters dominating, however the shift into a more overtly matriarchal focus, especially where that concerns a connection with nature confirms both Glenda and Cadi as the most vital characters, with performances to match.

The influences of Euro and Asian horror are felt deeply across the film, but the specific positioning of the film’s politics and exploration of themes separate it effectively enough that it never feels like entirely direct homage, but a fusion of the two to create something more fresh. It is clear from the construction of the film that both director Lee Haven Jones and writer Roger Williams are keen horror fans, having a distinct eye for troubling imagery and an awareness of how horror can be utilised to deliver a message. During a post-film Q&A the team referred to the horror in the film as a kind of Trojan Horse to deliver that messaging. That the film has managed to fuse a specifically Welsh message in the Welsh-language while also pulling off some of the most seductively disturbing horror imagery is fiercely impressive. Those who struggle with a slow burn may find their patience tested at times, but the pay-off makes expert use of those ominous beginnings. The refusal to be tied to any one mythology or lore affords the film further freedom, while also hinting at a wider legacy of the story behind The Rise, which offers a tempting opportunity for expansion.

With an exploration of the personal responsibility one has to roots, space and the negotiations we all undergo to make space in the world, this horror has a lot to chew over. On a slightly more flippant note, well done to the team involved for securing a go-to Halloween costume for any Welsh woman for the next few years.

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Film Review] A Wounded Fawn (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484054446-7R9YKPA0L5ZBHJH4M8BL/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.42.24.png)

![[Film Review] Perpetrator (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695483561785-VT1MZOMRR7Z1HJODF6H0/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.32.55.png)

![[Film Review] Mercy Falls (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695482997293-E97CW9IABZHT2CPWAJRP/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.27.27.png)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

If you know me at all, you know that I love, as many people do, the work of Nic Cage. Live by the Cage, die by the Cage. So, when the opportunity to review this came up, I jumped at it.